নির্বাহী সারসংক্ষেপ

This report does not represent the views of the Inquiry. The information reflects a summary of the experiences that were shared with us by attendees at our Roundtables in 2025. The range of experiences shared with us has helped us to develop themes that we explore below. You can find a list of the organisations who attended the roundtable in the annex of this report.

This report contains descriptions of homelessness, mental health impacts, addiction and psychological difficulties. These may be distressing to some. Readers are encouraged to seek support if necessary. A list of supportive services is provided on the UK Covid-19 Inquiry website.

In May 2025, the UK Covid-19 Inquiry held a roundtable to discuss the impact of the pandemic on the housing and homelessness sector. This roundtable was held through two group discussions with housing and homelessness organisations.

There was consensus that the guidance produced by the government for the sector during the pandemic lacked the specificity needed for housing and homelessness organisations and services to follow easily. For example, there was an absence of guidance for homelessness hostels to run shared facilities and prevent Covid-19 spreading. In some cases, organisations decided to tailor the guidance provided to make it more relevant to their service. Service providers and local authorities also collaborated to develop their own guidance that supported effective implementation of the measures.

Representatives described some positive and decisive interventions by the government, which they said helped mitigate the impact on the sector. This included the introduction of the Everyone In initiative which was implemented by local authorities in England. The initiative provided short-term accommodation for people sleeping rough or at risk of sleeping rough and those living in accommodation where self-isolation was not possible. This initiative highlighted the scale of hidden homelessness1 through, for example, ’sofa surfing’, as more people came forward to receive temporary accommodation than expected. Many returned to rough sleeping or insecure accommodation once the initiative ended.

Representatives thought that the pandemic exposed the UK’s long-term underinvestment in social housing. Hotels and other forms of accommodation were repurposed to act as temporary accommodation for the duration of the Everyone In initiative. There were strong concerns that the use of this form of accommodation has continued, which was seen as financially unsustainable for local authorities given the high costs.

Other government initiatives were introduced during the pandemic to improve housing security for private and social housing tenants, such as a ban on evictions. While seen as effective in reducing the immediate impact of the pandemic on tenants, the security this offered was said to be short-lived and ended when the ban was lifted on 23 August 2020. Representatives also viewed temporary benefit reforms positively, particularly the £20 weekly Universal Credit uplift and the removal of household benefit limits. These measures eased financial burdens temporarily, but they were considered short-term solutions which people could not continue to rely on after the pandemic.

The quality of housing was said to have declined during the pandemic because the rate at which repairs occurred during periods of lockdown slowed or stopped altogether. This created backlogs of repairs, with some landlords accused of using the pandemic as a reason to delay essential maintenance.

With people confined to their homes during lockdown, issues like overcrowding and damp and mould intensified, negatively affecting people’s physical and mental health. Rising energy costs associated with being at home also placed further financial pressure on households, particularly for those living in poorly insulated homes.

The housing and homelessness workforce, including those working in housing associations, homelessness services and housing advocacy organisations, was under significant pressure during the pandemic. The workforce was not initially granted key worker status, preventing them from accessing essential Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and childcare. This led to them feeling undervalued and put them at risk of contracting the virus. The workforce was praised for filling gaps left by the closure of face-to-face support by statutory services, taking on additional responsibilities that mental health and addiction services would normally provide. However, doing so increased stress on staff.

Despite early fears that mortality rates from Covid-19 would be higher amongst homeless people, this was not the case. Representatives from England believed this was due to the government and the sector’s rapid response to provide support and temporary accommodation through the Everyone In initiative. Additionally, the vaccination programme was said to have created an opportunity to engage with homeless people and provide a route to address other underlying health issues, particularly for those who had not accessed healthcare for decades.

However, the pandemic impacted access to support services for homeless people and those housed in temporary accommodation. For instance, there was reduced access to mental health, drug and alcohol and other advice services due to the shift away from face-to-face support to predominantly online support. This change left people with complex needs linked to past traumas, mental and physical health problems and addictions, without adequate support.

During the pandemic, accommodation support shifted from face-to-face provision to online and telephone support, leaving those without phones or internet access unable to engage with these services. However, some demographic groups such as younger people found digital support easier to use and the move online improved their access to services.

There was agreement that the sector should prioritise learning from the experiences of those who accessed temporary accommodation during the pandemic to make future plans more effective. Representatives thought that in future pandemics the housing and homelessness workforce should be recognised as key workers from the beginning of any pandemic or civil emergency to ensure they are better protected and supported. They felt it was essential that housing and homelessness sector expertise is incorporated in emergency planning and response and that clear and specific guidance is developed for the sector.

- Hidden homelessness: Refers to people who are without a permanent home but are not visible to officials or the public. They often live in temporary or unsuitable accommodation, such as ’sofa surfing’ with friends and family, in overcrowded or precarious households, in squats, or in tents or cars.

মূল থিমগুলি

Impact of government guidance

At the beginning of the pandemic, there was just one set of government guidance for the housing and homelessness sector which was described as generic and lacking detail about how services should operate to keep people safe. This led to inconsistencies in the way the guidance was implemented across different services and organisations within the sector. For example, Shelter said that the lack of specific guidance for hostels, where residents often share bathrooms, led to confusion about how to implement rules about isolation and social distancing if someone had Covid-19 symptoms. Shelter thought this put hostel residents at greater risk of Covid-19 infection. It also increased the stress experienced by hostel staff, who felt responsible for preventing people from contracting Covid-19.

| " | What would you do if someone’s got Covid-19 in a hostel, do you evict them because they might infect the hostel? Where do you isolate? There was a lack of operating guidance.”

– Shelter |

As the pandemic continued, local authorities developed additional guidance to supplement UK government advice, whilst devolved governments issued their own separate guidance for the housing and homelessness sector. For example, the Welsh government produced guidance for services in Wales aimed at supporting rough sleepers during the pandemic.

| " | I think in that initial instruction it was very Westminster focused and the government had to say how they would implement it, but as the pandemic went on, the different governments took different approaches.”

– Mind |

In some cases, organisations developed their own guidance to better support the implementation of Covid-19 measures for frontline services. For instance, The Wallich, created their own guidance to clarify procedures for homelessness workers in Wales in order to implement rules effectively and ensure safety. The Welsh government later adopted this more broadly.

| " | There was no guidance for homelessness, and the [Government] were telling us to follow health and social care guidance which didn’t fit. So, we actually met and wrote specific guidance for housing and homelessness.”

– The Wallich |

Shelter gave an example of their service hubs in urban areas working with local authorities to provide specific guidance, enabling them to continue effectively delivering their services to local homeless people. However, representatives explained that not all local authorities across the UK have strong relationships with the sector. In those areas, there was less coordination and the sector felt less supported, leading to a lack of effective and clear guidance for services to follow.

| " | [Simon Community] chair the agency group on guidance and we were able to help with that because we had had civil servants in the room, so rather than top-down it was more our experience upwards, it was a different dynamic and it was much much better.”

– Simon Community |

Impact of government interventions

The Everyone In initiative

The Everyone In initiative in England involved providing housing to people who were homeless or living in places where they could not socially distance safely. A range of alternative accommodation became available and was used by local authorities as temporary housing, such as budget hotels, B&Bs and holiday lets, that were left mostly empty due to restrictions on travel. These properties became available to local authorities as temporary housing solutions. Representatives saw this approach as a good way to provide temporary support to as many homeless people as possible to access safe accommodation.

Representatives commended the Everyone In initiative for adopting a person centred approach that prioritised individuals’ needs over immigration status. They particularly welcomed the government guidance clarifying that immigration circumstances should not prevent access to emergency accommodation. This represented a positive change from the typical approach used when engaging with those with insecure immigration status.

| " | I think from a migrant homelessness point of view, really needing to look at the person, the need, before immigration status…we saw that with Everyone In. We saw positive consequences for individuals knowing what their rights were and knowing their options.”

– NACCOM – The No Accommodation Network |

The Everyone In initiative was thought to have identified people who were not previously known to homelessness services in the UK, described as ‘hidden homeless’, including people who were ‘sofa surfing’ or living in overcrowded conditions. This meant that support could be provided to a wider group of people who had not accessed housing and homelessness services previously. Representatives said that those living in these circumstances were likely to have accessed services through the initiative for the first time because social distancing requirements meant they could no longer live in shared spaces.

Although largely viewed as a positive intervention, Centrepoint explained that the Everyone In initiative could not provide appropriate support for those with complex needs, such as care leavers, those with mental health conditions, and people with drug and alcohol addictions. Those with complex needs were sometimes reluctant to access housing support, as they were uncomfortable with the idea of living in shared accommodation.

| " | In other parts of the country, people were put in budget hotels, with no support whatsoever. They didn’t know how long they’d be there, people were having terrible mental health crises…In some cases there were skeleton staff in the hotels, so [there were] hotel staff dealing with people who wanted to take their own life, having severe reactions because they couldn’t obtain drugs or alcohol, and they were completely untrained.”

– Shelter |

Representatives also said the accommodation provided by Everyone In was not set up to provide the level of safety that some people, particularly those who had experienced trauma, needed. For instance, St Mungo’s explained that hotel provisions were often mixed gender, creating an environment that was unsuitable for women with experience of trauma who sometimes required single-sex spaces. Additionally, hotels were considered inappropriate for care leavers and those with addictions, mental health conditions or complex needs, who often require more structured support that was only available through other housing options.

| " | There were some women put in some genuinely dangerous situations around people who may well have been perpetrators. I think women with complex trauma, sex workers who were really struggling to understand how to make ends meet, they were put in very dangerous risky situations in some of the congregate accommodation.”

– Cymorth Cymru |

NACCOM also raised concerns about the eligibility criteria of the initiative, which required individuals to be confirmed as either sleeping rough or residing in accommodation unsuitable for self-isolation. They believed this deterred certain groups from accessing support, particularly those with uncertain immigration status or hidden homeless. This reluctance stemmed from a perceived risk of rejection from the scheme, rather than actual ineligibility for assistance.

St Mungo’s stated that there was a 37% decline in rough sleeping during the pandemic, in part due to people accessing safe accommodation through the Everyone In initiative. This was welcomed as a positive intervention to support homeless people. Nevertheless, Shelter explained that by August 2021, the Everyone In initiative had supported only 1 in 4 homeless people moving into settled accommodation. Ultimately, most organisations reflected on the Everyone In initiative as a missed opportunity to have a long-term impact on reducing homelessness in England because there remained a large number of homeless people without permanent housing.

| " | In some areas we saw rough sleeping really dropped down… but in that first wave 35,000 people were supported through that [Everyone In] and it highlighted the number of people who were hidden homeless, at risk of rough sleeping or more extreme forms of homelessness that are hidden in the system and not counted. That’s still the case today.”

– Crisis |

Other government interventions

Government initiatives during the pandemic helped private and social housing tenants maintain more housing security in the short term. Representatives largely agreed that the ban on evicting tenants from rental properties was effective. However, they noted that when the ban was lifted on 23 August 2020, the positive impact was then immediately reversed. The lifting of the ban was said to have led to bidding wars and significant rent increases. There was also a sudden rise in no fault evictions2 and migrants being evicted from their state-provided accommodation.

The government introduced other temporary policies during the pandemic, which aimed to support people in affording housing and providing greater financial security. This included a £20 weekly increase to Universal Credit and the suspension of the benefit cap limiting how much support one family could receive. Representatives felt that whilst these measures eased the financial strain of the pandemic for some households, they were temporary interventions that ceased once the pandemic ended. As a result, people were left in the same financial position they were in before the pandemic, or potentially worse off. They also highlighted that the pandemic accelerated previous funding challenges faced by the sector.

| " | [Homelessness] initially decreased which shows that bold intervention at pace is possible, but then afterwards, in my opinion, what we’re seeing now is all the issues there were before have been exacerbated, it’s like a pandemic induced housing crisis now, with all the extra stuff that the pandemic caused.”

– Mind |

The end of pandemic housing initiatives was said to have disproportionately affected those at higher risk of homelessness, such as individuals with insecure immigration status, women and young people.

Impact on housing availability

There was consensus that the pandemic highlighted the need for increased investment in UK housing, particularly within the social housing sector, which representatives felt had been underfunded for decades. Crisis noted that the lack of social housing meant that councils needed to turn to the private rental sector and hotels to provide temporary accommodation during the pandemic.

There were concerns that the pandemic had normalised the use of hotels and B&Bs to accommodate homeless people, rather than seeing their use as a specific emergency measure. Shelter shared examples of families staying for months in cramped and overheated hotel rooms, with families often sharing beds in a single room, unsure when they may be told to move on. This was said to have put a strain on relationships and the confined space heightened the risk of contracting Covid-19.

| " | [The] pandemic… normalised temporary accommodation that we’ve never got away from… It increased during Covid-19 and I don’t think we think of that as a short-term blip, it’s the new normal.”

– St Mungo’s |

Simon Community also considered that the lack of available emergency accommodation provided by the council meant that the private rental sector in Northern Ireland could charge high rents, contributing to the wider rise in prices in the rental market

Impact on living conditions

Repairs and maintenance

The quality of housing was said to have decreased during the pandemic because some repairs or maintenance operators temporarily closed or scaled back their maintenance services. This meant some people were living with serious problems, such as no hot water or damp or mouldy conditions, for long periods. This had a negative impact on their physical and mental health.

Social housing providers with in-house maintenance teams were able to resume repairs once pandemic restrictions allowed them into properties again. However, those who relied on external maintenance contractors found that many had shut down and furloughed staff, which meant residents had to live with problems for longer. Shelter said that private landlords reported similar challenges in availability of workers to carry out repairs. They noted that private rental properties are often in a worse state of repair than social housing properties, because landlords can be less responsive and there is often insufficient investment in property maintenance. They said this worsened during the pandemic, as some landlords used Covid-19 as an excuse to avoid conducting necessary repairs.

| " | From our perspective, there were more repairs not being done, with Covid as the reason. Sometimes that was true, but also it was used a lot as an excuse by landlords. Things like people who didn’t have hot water for two months.”

– Acorn |

Representatives said that delays to maintenance repairs during the pandemic created a backlog and there are still ongoing problems with the speed of repairs. Acorn said that up until 2024 they were still carrying out repairs for issues first reported during the pandemic. In the long-term, this has contributed to the gradual decline in the quality of housing and people’s living conditions.

There were also concerns that people may not have reported maintenance issues during the pandemic. NACCOM said this may have been due to residents’ concerns about being evicted from private rentals if landlords were unwilling to deal with repairs, or their fears about contracting Covid-19 from repair workers entering their homes.

Overcrowding

The pandemic meant that people were spending more time at home, sometimes in overcrowded conditions, particularly for people living in shared houses and houses of multiple occupancy (HMOs). Representatives said this disproportionately affected people from lower social economic backgrounds, as they were more likely to be living in poorer quality housing. St Mungo’s referred to overcrowding disproportionately affecting people from some ethnic backgrounds. For example, they said 2% of White British households were overcrowded compared to 25% of Arab households.

| " | I think people’s experience of lockdown was based on the quality of their housing and the amount of space they had. Particularly for people who were poorer, people who had been in temporary accommodation before the pandemic, it’s a small 6 foot by 10-foot room you’re in, maybe with a shared bathroom.” – St Mungo’s |

Representatives said people living in HMOs were in close proximity in communal areas like shared kitchens and bathrooms, which increased the risk of overcrowding and Covid-19 transmission. Acorn highlighted that the lack of space could lead to tensions, particularly when some individuals were shielding or adhering to rules about social distancing, while others did not. St Mungo’s described increased risks from Covid-19 in HMOs, with key workers who were in face-to-face contact with others in their jobs, mixing with housemates who were working from home. This situation left residents feeling uneasy since they did not feel in control of the risk of contracting Covid-19 at home.

| " | We had tenants, their parents had cancer when people weren’t adhering to the rules that they lived with. There was added friction that will happen when you all live together, then if you have different interpretations of what’s acceptable, it’s stressful.”

– Acorn |

Larger numbers of people sharing living spaces also increased levels of condensation within the home and consequently the level of damp and mould in houses. This affected living conditions and put people’s respiratory health at risk.

Energy costs

Energy costs also rose because people spent more time at home. Representatives said that this added financial pressure, particularly for households that were already struggling to afford their housing. Older houses were also said to have poorer insulation, or be in poorer condition, which made them less energy efficient and more costly.

| " | On affordability and quality, people working from home were either really cold or they were spending loads of money to put the heating on. [But it was] not just people working from home. There was an impact there, it wasn’t thought about. Normally people would be at work or school to stay warm.”

– Acorn |

Impact on housing and homelessness workforce

Key worker status

The housing and homelessness workforce were not recognised as key workers until later in the pandemic. Organisations said this sent a message to workers that wider society did not recognise the role they were playing. The delay in receiving key worker status also meant they did not receive the practical support given to other key workers, including access to childcare and PPE. Representatives agreed that not having key worker status made it more challenging for staff in the sector to perform their roles. In particular, the shortage of PPE made it hard for them to protect themselves and the people they worked and lived with. Workers were described as feeling undervalued, forgotten about and fearful about contracting Covid-19, all of which impacted morale.

| " | The pandemic underscored the key role housing and homelessness charities play but the sector didn’t get the recognition it deserved, staff couldn’t get access to childcare, the sector wasn’t sufficiently included in pandemic planning prior to the pandemic.”

– Salvation Army |

Despite not having key worker status, staff were expected to continue working. Mind reported that those in the sector who were working from home felt forced to juggle personal pressures while supporting people with increasingly complex housing and mental health needs. Workers felt this was unsustainable and made them concerned about contracting Covid-19 and spreading it to family members at home.

| " | I don’t think we’re a sector that looks for people to cheer and clap them, but people just get on with their jobs. There was a real risk and fear due to the lack of PPE and lack of statutory support and guidance for the sector. The homeless sector needed to be recognised as key workers.”

– Homeless Connect (Northern Ireland) |

Closure of statutory and public services

During the pandemic some statutory support services, including mental health services and drug and alcohol services, closed face-to-face support or reduced their capacity. This was said to have resulted in charities taking on a large amount of the service provision within the sector. This created frustration amongst those organisations as they felt unsupported and abandoned.

| " | I’ve got a quote from one of the evaluations, it just says, “staff are heroes” and they put themselves on the line to support vulnerable people during the pandemic where other services shut down. I wanted to highlight the importance of the staff and the impact it had on our staff.”

– The Wallich |

Local authority housing departments also redeployed staff to Covid-19 response roles. Representatives highlighted that this shift away from face-to-face service delivery, particularly within local authority teams responsible for advising people on housing issues, has continued post-pandemic and continues to affect service provision.

They also stated that the prolonged closure of courts and subsequent backlogs had serious operational consequences for housing organisations. These closures resulted in a large backlog of cases, with eviction proceedings taking two to three years to complete. This resulted in substantial financial costs to housing organisations, deeply impacting their ability to help more beneficiaries.

Representatives reflected positively on how the sector managed to continue offering services in challenging circumstances and adapt to meet people’s needs. However, workers encountered people with more complex needs whom they were not trained to support.

Volunteers

There was widespread praise for the work of volunteers during the pandemic to support the housing and homelessness sector. For instance, St Mungo’s reported that about 400 people volunteered to help, collectively contributing over 20,000 hours towards promoting awareness of rough sleeping. This level of volunteering was unusual outside the Christmas period.

Impact on the health and wellbeing of homeless people

Mortality rates

At the start of the pandemic, it was expected that the health of homeless people would be particularly affected by the virus. Representatives believed that the sector’s efforts and initiatives like Everyone In helped prevent the worst-case scenarios for Covid-19 deaths among homeless people. Centrepoint and Mind highlighted research from University College London (UCL) that found that there were 16 Covid-19 deaths amongst homeless people during the first wave of the pandemic in the UK and that work by the housing and homelessness sector prevented 20,000 infections and 266 homeless deaths.3 This work included closing night shelters, providing safe single-rooms, ensuite accommodation and prioritising those who were deemed clinically vulnerable, for specialist health and care support as part of the Everyone In initiative. There were concerns, however, that the research had missed out hidden homeless people, as their living circumstances were not included in this study. The study also did not account for families in statutory temporary accommodation who might have been vulnerable to the virus.

| " | What I would say is, I think that [the UCL research] was particularly focused on people who were [street homeless and not people in temporary accommodation]. There would have been a lot of people in families in statutory [temporary] accommodation who were very vulnerable to the virus and I’m not sure it took that into account.”

– Centrepoint |

St Mungo’s said 2020 provided opportunities to connect homeless people more with health services. St Mungo’s and Cymorth Cymru found that the vaccination programme provided an opportunity to not only engage with people about Covid-19, but address other unmet health needs, such as Hepatitis. Cymorth Cymru felt that this led to people with poor health getting help that they had not had in 20 years.

| " | Another thing that worked well was general access to GPs, so people with unmet health needs who hadn’t met with a GP and hadn’t interacted with anyone outside of A&E, were getting medical needs met and that improved their health overall. The vaccination programme allowed us to engage with people not just around Covid but hepatitis and things like that.”

– St Mungo’s |

As the pandemic progressed, representatives noted that the overall number of homeless people who died each year in England and Wales began to rise again. In 2021, there were 741 reported deaths, an increase from 688 in 2020 and slightly less than the 778 recorded in 2019. The reasons behind this increase were not discussed. Simon Community emphasised that in Northern Ireland mortality rates for the homeless community also spiked later in the pandemic.

Impact on access to support services

Mental health and wellbeing support

Representatives felt that the pandemic made it harder for homeless people to access some mental health and advice services. For instance, increasing numbers of people in temporary accommodation received inadequate mental health support, as staffing levels and available resources could not meet the scale of demand. There was a particularly negative impact on those with mental health conditions and complex needs. Homeless Connect (NI) emphasised that people with more complex needs found the lack of support during the pandemic made their mental health and/or addiction issues worse. For some, this problem has continued.

Services provided by homelessness charities and housing advocacy organisations, mostly transitioned online and this created significant barriers for service users. Mind reported that people without phones or internet access were unable to get the support they needed. Many hotels did not provide internet access, which prevented residents from accessing digital support services. However, the shift to digital or telephone support benefited some young people, who preferred online help and found it easier to access.

| " | People who were digitally excluded. There are loads of people out there with no phones, no access to the internet, and it’s a massive issue. We were fortunate that for people in our services we could get donations, and we’ve got Wi-Fi, but people who aren’t in services it was a massive problem for them. Just getting through to anyone in the local authority, people are running out of money, on hold, running out of battery.”

– Mind |

Immigration support

NACCOM reported that people with insecure immigration status, who were housed in hotels during the pandemic, gained better access to immigration advice, as some hotels provided immigration support services on site. This enabled them to ask questions about the migration system, understand their rights more clearly, and in some cases, regularise their immigration status.

| " | The access to immigration advice, in a lot of the hotels, there were a lot of access. People had access and time to engage with it. We saw some really good outcomes in terms of people who could regularise their status, they knew their rights.”

– NACCOM |

-

-

- Section 21 no fault eviction: Is a type of eviction notice in England that allows a landlord to regain possession of their property without giving a reason for the eviction. It is often called a “no-fault” eviction because the landlord does not have to prove the tenant did anything wrong, such as having rent arrears.

- University College London (2022). Protecting rough sleepers during the pandemic. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/impact/case-studies/2022/apr/protecting-rough-sleepers-during-pandemic

-

Lessons for future pandemics

- Recognise the importance of the home: Future pandemic policies should acknowledge how essential good quality housing is for people’s wellbeing and resilience, particularly in emergencies when people need to spend more time at home.

- Recognise and invest in the sector: To improve preparedness and resilience in future pandemics, representatives thought there should be an increase in long-term funding for homelessness services and the social housing sector.

- Recognise those working in the sector as key workers: Representatives felt that the housing and homelessness frontline workforce should be recognised as key workers at the start of the pandemic. This would provide them with the benefits of being a key worker, such as access to personal protective equipment and childcare support.

- Develop clear guidance tailored to housing and homelessness services: Representatives felt there was a need to develop tailored guidance for housing and homelessness services in any future pandemic or emergency, so that it is relevant to the sector and can be easily understood and implemented. They felt this could happen by bringing sector expertise into national and local emergency planning, to ensure that services are precisely tailored to meet emerging needs in a crisis.

- Improve cross-sector and government coordination: There was a desire to create working groups that consolidate housing, healthcare, addiction and immigration services to ensure comprehensive care and regular collaboration during a pandemic or emergency. To enhance collaboration, they wanted to establish clear communication channels between the sector and government to help improve government guidance and reduce confusion.

- Create contingency plans for temporary housing supply: Representatives said that temporary housing policies enacted in an emergency, should have built in strategies rapidly to secure accommodation in a pandemic that goes beyond relying on expensive hotels and B&Bs.

- Prioritise targeted support for vulnerable groups: Housing and homelessness services introduced during pandemics should be designed to cater specifically to different demographic groups to prevent exclusion of the most vulnerable. For instance, tailoring services to address the needs of survivors and victims of domestic abuse, care leavers, those with mental health conditions, including those who have experienced trauma and/or those with addictions or migrants, to ensure they have positive experiences and feel appropriately supported.

- Provide a mix of digital and face-to-face support: Representatives felt there was a need to balance digital service delivery with vital face-to-face interactions during any future pandemic, to ensure that support is accessible to those who need it most, especially those who are digitally excluded.

- Learn from people who experienced homelessness during the pandemic: Representatives felt it was essential to conduct research with individuals who have had direct experience of using emergency accommodation during the pandemic. They thought conducting such research would provide invaluable feedback for future pandemic responses.

Annex

Roundtable structure

In June 2025, the UK Covid Inquiry held a roundtable to discuss the impact of the pandemic on the housing and homelessness sector. This roundtable included two breakout group discussions.

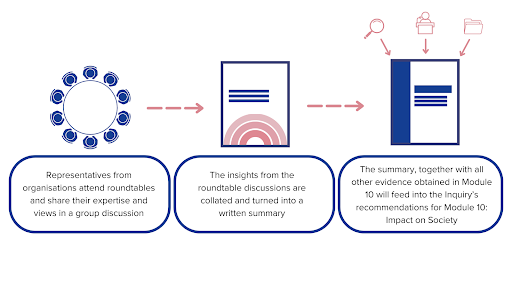

This roundtable is one of a series being carried out for Module 10 of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry, which is investigating the impact of the pandemic on the UK population. The module also aims to identify areas where societal strengths, resilience, and or innovation reduced any adverse impact of the pandemic. The roundtable was facilitated by Ipsos UK and held at the UK Covid-19 Inquiry Hearing Centre.

A diverse range of organisations were invited to the roundtable; the list of attendees includes only those who attended the discussion on the day. Attendees at the two breakout group discussions were representatives for:

Breakout group 1

- Acorn

- Homeless Connect (NI)

- NACCOM – The No Accommodation Network

- St Mungo’s

- Cymorth Cymru

Breakout group 2

- কেন্দ্র বিন্দু

- মন

- সংকট

- Simon Community

- আশ্রয়

- The Wallich

- Salvation Army

Figure 1. How each roundtable feeds into M10