এই রেকর্ডে অন্তর্ভুক্ত কিছু গল্প এবং বিষয়বস্তুর মধ্যে রয়েছে মৃত্যু, মৃত্যুর কাছাকাছি অভিজ্ঞতা, নির্যাতন, যৌন শোষণ ও আক্রমণ, জোরপূর্বক, অবহেলা এবং উল্লেখযোগ্য শারীরিক ও মানসিক ক্ষতির উল্লেখ। এগুলো পড়তে কষ্টদায়ক হতে পারে। যদি তাই হয়, তাহলে পাঠকদের প্রয়োজনে সহকর্মী, বন্ধুবান্ধব, পরিবার, সহায়তা গোষ্ঠী বা স্বাস্থ্যসেবা পেশাদারদের কাছ থেকে সাহায্য চাইতে উৎসাহিত করা হচ্ছে। যুক্তরাজ্যের কোভিড-১৯ অনুসন্ধান ওয়েবসাইটে সহায়ক পরিষেবার একটি তালিকা দেওয়া আছে।

মুখপাত্র

এটি যুক্তরাজ্যের কোভিড-১৯ তদন্তের জন্য ষষ্ঠ এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স রেকর্ড।

কোভিড-১৯ মহামারী যুক্তরাজ্যের জন্য অভূতপূর্ব অর্থনৈতিক চ্যালেঞ্জ নিয়ে এসেছে। এই রেকর্ডটি এই চ্যালেঞ্জিং সময়ের মধ্যে অর্থনীতিকে সমর্থন করার জন্য চারটি সরকারের প্রচেষ্টার দ্বারা প্রভাবিত হাজার হাজার মানুষের অভিজ্ঞতা একত্রিত করে।

এতে যারা চাকরিতে ছিলেন এবং যারা করেননি, যারা আর্থিক সহায়তা পেয়েছেন এবং যারা পাননি এবং যারা তাদের প্রতিষ্ঠানের জন্য সিদ্ধান্ত গ্রহণের ভূমিকায় ছিলেন বা তাদের জন্য সিদ্ধান্ত নেওয়া হয়েছিল তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা অন্তর্ভুক্ত রয়েছে।

রাতারাতি আয়ের পরিবর্তন ঘটে, যার ফলে চাপ এবং অনিশ্চয়তা তৈরি হয়। কিছু পণ্য ও পরিষেবার অ্যাক্সেস হঠাৎ বন্ধ হয়ে যায়, আবার কিছু ক্ষেত্রে নতুন ব্যবসায়িক সুযোগ তৈরি হয়। দাতব্য প্রতিষ্ঠানে কর্মরত পরিষেবা প্রদানকারীদের তাদের মডেল পরিবর্তন করতে হয়েছিল যাতে তারা অভাবী মানুষের জন্য কাজ চালিয়ে যেতে পারে। কর্মীদের দায়িত্বে থাকা ব্যবসার মালিকরা আগামী সপ্তাহটি কী নিয়ে আসবে তা নিয়ে অনিশ্চিত ছিলেন। মানুষকে ছুটিতে রাখা হয়েছিল, যা কারও কারও কাছে সুরক্ষার জালের প্রতিনিধিত্ব করে; অন্যদের কাছে এটি উদ্দেশ্যের অনুভূতি থেকে বঞ্চিত করেছিল। কিছু মানুষ এখনও আজকের অর্থনৈতিক প্রতিক্রিয়ার প্রভাব অনুভব করছেন।

যারা সময় বের করে যুক্তরাজ্যের কোভিড-১৯ তদন্তের সাথে তাদের গল্প ভাগ করে নিয়েছেন এবং ভবিষ্যতে ভিন্নভাবে কী করা যেতে পারে সে সম্পর্কে তাদের পরামর্শ দিয়েছেন, তাদের সকলের প্রতি আমরা কৃতজ্ঞ।

ওভারভিউ

এই সংক্ষিপ্তসারটি মহামারী মোকাবেলায় সরকারের অর্থনৈতিক প্রতিক্রিয়া সম্পর্কিত আমরা যে অসংখ্য গল্প শুনেছি তার থিমগুলির একটি উচ্চ-স্তরের সারসংক্ষেপ প্রদান করে।

গল্পগুলি কীভাবে বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছিল

তদন্তের সাথে ভাগ করা প্রতিটি গল্প বিশ্লেষণ করা হয় এবং রেকর্ড নামক এক বা একাধিক বিষয়ভিত্তিক নথিতে অবদান রাখবে। এই রেকর্ডগুলি এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স থেকে প্রমাণ হিসাবে তদন্তে জমা দেওয়া হয়। এর অর্থ হল তদন্তের ফলাফল এবং সুপারিশগুলি মহামারী দ্বারা সবচেয়ে বেশি ক্ষতিগ্রস্তদের অভিজ্ঞতার উপর ভিত্তি করে তৈরি করা হবে।

এই রেকর্ডে, অবদানকারীরা মহামারীর অর্থনৈতিক প্রতিক্রিয়া সম্পর্কিত তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা বর্ণনা করেছেন। অনুসন্ধান দল এবং গবেষকরা বলেছেন:

- অনুসন্ধানের সাথে অনলাইনে শেয়ার করা ৫৪,৮০৯টি গল্প বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছে, প্রাকৃতিক ভাষা প্রক্রিয়াকরণের মিশ্রণ ব্যবহার করে (আরও বিস্তারিত পৃষ্ঠা ১৪ তে পাওয়া যাবে) এবং গবেষকরা লোকেরা কী ভাগ করেছেন তা পর্যালোচনা এবং তালিকাভুক্ত করেছেন।

- স্বেচ্ছাসেবী, সম্প্রদায় এবং সামাজিক উদ্যোগের (VCSEs) ব্যক্তি, ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক এবং নেতাদের সাথে ২৭৩টি গবেষণা সাক্ষাৎকার থেকে সংগৃহীত বিষয়বস্তু।1.

- ইংল্যান্ড, স্কটল্যান্ড, ওয়েলস এবং উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ডের শহর ও শহরের জনসাধারণ এবং সম্প্রদায়ের গোষ্ঠীগুলির সাথে "এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স লিসেনিং ইভেন্টস" এর থিমগুলিকে একত্রিত করা হয়েছে।

এই রেকর্ডে মানুষের গল্পগুলিকে কীভাবে একত্রিত করা হয়েছিল এবং বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছিল সে সম্পর্কে আরও বিশদ ভূমিকা এবং পরিশিষ্টে অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা হয়েছে। নথিটি বিভিন্ন অভিজ্ঞতাকে প্রতিফলিত করে, সেগুলিকে একত্রিত করার চেষ্টা না করেই, কারণ আমরা স্বীকার করি যে প্রত্যেকের অভিজ্ঞতা অনন্য।

পুরো রেকর্ড জুড়ে, আমরা এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের সাথে তাদের গল্প শেয়ার করা ব্যক্তিদের 'ব্যক্তি', 'ব্যবসায়িক মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক', 'ভিসিএসই নেতা' এবং, যদি তিনটি গ্রুপকেই উল্লেখ করা হয়, 'অবদানকারী' হিসাবে উল্লেখ করেছি। তদন্তের প্রমাণ এবং মহামারীর সরকারী রেকর্ডে তাদের গুরুত্বপূর্ণ ভূমিকা রয়েছে। যেখানে উপযুক্ত, আমরা তাদের সম্পর্কে আরও বর্ণনা করেছি (উদাহরণস্বরূপ, একটি ব্যবসা কোন খাতে ছিল) অথবা তারা কেন তাদের গল্প শেয়ার করেছে (উদাহরণস্বরূপ, একজন ব্যক্তি যিনি ছুটিতে গিয়েছিলেন)।

কিছু গল্প উদ্ধৃতি এবং কেস চিত্রের মাধ্যমে আরও গভীরভাবে অনুসন্ধান করা হয়েছে। নির্দিষ্ট অভিজ্ঞতা এবং মানুষের উপর এর প্রভাব তুলে ধরার জন্য এগুলি নির্বাচন করা হয়েছে। উদ্ধৃতি এবং কেস চিত্রগুলি মানুষের নিজস্ব ভাষায় রেকর্ডটি তৈরি করতে সহায়তা করে। অবদানগুলি বেনামে রাখা হয়েছে। গবেষণা সাক্ষাৎকার থেকে নেওয়া কেস চিত্রের জন্য আমরা ছদ্মনাম ব্যবহার করেছি। অন্যান্য পদ্ধতি দ্বারা ভাগ করা অভিজ্ঞতার ছদ্মনাম থাকে না।

মহামারীর অর্থনৈতিক প্রভাব

তাৎক্ষণিক প্রভাব

যখন লকডাউন বিধিনিষেধ ঘোষণা করা হয়েছিল, তখন ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক, ভিসিএসই নেতা এবং ব্যক্তিরা এই খবরটি হতবাক বলে মনে করেছিলেন এবং তাদের কাজ এবং আর্থিক ভবিষ্যত সম্পর্কে খুব অনিশ্চিত বোধ করেছিলেন। তারা প্রায়শই তাদের কাজ এবং আয়ের তাৎক্ষণিক ব্যাঘাতের সম্মুখীন হন, যার পরে চলমান লকডাউন এবং অর্থনৈতিক অনিশ্চয়তার ফলে দীর্ঘমেয়াদী প্রভাব পড়ে।

ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা তাদের প্রতিষ্ঠানের উপর মহামারীর তাৎক্ষণিক প্রভাব সম্পর্কে আমাদের জানিয়েছেন:

- লকডাউন ঘোষণার সাথে সাথেই অনেককে তাদের ব্যবসা প্রতিষ্ঠান বন্ধ করে দিতে হয়েছিল, যার ফলে আর্থিক অনিশ্চয়তা দেখা দেয় এবং বিধিনিষেধ কতদিন স্থায়ী হবে তা নিয়ে উদ্বেগ দেখা দেয়।

- কেউ কেউ দূরবর্তী কাজে স্থানান্তরিত হয়ে বা অনলাইনে চলে যাওয়ার মাধ্যমে দ্রুত অভিযোজিত হয়েছিলেন, আবার কেউ কেউ ব্যক্তিগত কার্যকলাপের উপর নির্ভর করে কাজ চালিয়ে যেতে পারেননি এবং আয় দ্রুত হ্রাস পেয়েছে।

- যারা ব্যক্তিগতভাবে প্রয়োজনীয় পরিষেবা প্রদান করেন (যেমন VCSE সংস্থাগুলি যারা জনস্বাস্থ্য-সম্পর্কিত বা সংকট সহায়তা পরিষেবা প্রদান করে) তাদের কর্মী এবং গ্রাহকদের জন্য সুরক্ষা ব্যবস্থা বাস্তবায়নের জন্য দ্রুত মানিয়ে নিতে হবে।

- ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপকরা কর্মীদের অতিরিক্ত ছাঁটাই করার মানসিক ক্ষতির বর্ণনা দিয়েছেন।

| " | একদিন, আমাকে আমার কর্মীদের 80%-তে ফোন করে বলতে হয়েছিল যে তাদের আর চাকরি নেই বলে তাদের ছাঁটাই করতে হবে। আর আমি কেঁদেছিলাম, সারা রাত ঘুমাইনি, আমি খুব বিরক্ত ছিলাম। আমার কাছে এমন কিছু লোক ছিল যারা সাত-আট বছর ধরে আমার জন্য কাজ করেছিল, যাদের আমাকে বলতে হয়েছিল, 'আমি খুবই দুঃখিত, আমি আক্ষরিক অর্থেই আপনাকে আর বেতন দিতে পারছি না কারণ আমাদের কোনও ব্যবসা নেই।'

-ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা খুচরা ব্যবসার মালিক |

ব্যক্তিরা লকডাউনের তাৎক্ষণিক প্রভাবগুলিও ভাগ করে নিয়েছেন:

- অনেকেই তাদের চাকরি এবং আর্থিক অবস্থার কী হবে তা নিয়ে চিন্তিত ছিলেন।

- যারা জনসাধারণের মুখোমুখি ভূমিকায় ছিলেন তাদের অপ্রয়োজনীয় বলে মনে করা হত, তারা প্রায়শই কাজ বন্ধ করে দিতেন। তারা ভয় এবং অনিশ্চয়তা অনুভব করতেন।

- যাদের তাৎক্ষণিকভাবে চাকরিচ্যুত করা হয়েছিল, তাদের মধ্যে কেউ কেউ অন্য কাজ খুঁজে পাওয়ার ব্যাপারে আশাবাদী ছিলেন না এবং গভীরভাবে অস্থির বোধ করেছিলেন।

- মহামারীর শুরুতে অর্থনৈতিকভাবে দুর্বল পরিস্থিতিতে বসবাসকারী অনেকেরই কোনও স্থায়ী চাকরি ছিল না এবং কোনও সঞ্চয়ও ছিল না অথবা ইতিমধ্যেই আর্থিকভাবে বা ঋণের মধ্যে ডুবে ছিল।

- মহামারী চলাকালীন যাদের আয় স্থিতিশীল ছিল, যেমন পেনশনভোগীরা, তারা আমাদের জানিয়েছেন যে তারা খুব বেশি আর্থিক প্রভাব অনুভব করেননি তবে তারা বিচ্ছিন্নতার অভিজ্ঞতা অর্জন করেছেন।

- যারা ইভেন্ট এবং বিনোদনে কাজ করছিলেন তারা উল্লেখযোগ্যভাবে প্রভাবিত হয়েছিলেন কারণ সশরীরে সমাবেশ সম্ভব হয়নি।

| " | আমি তখন, এবং এখনও বেশিরভাগ ক্ষেত্রেই একজন ফ্রিল্যান্সার, স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী শিল্পী, সঙ্গীতশিল্পী এবং টেকনিশিয়ান ছিলাম ... লাইভ ইভেন্ট এবং অনুষ্ঠানের জন্য। এবং আমি [দ্য] সার্কাসের সাথে ট্যুরে ছিলাম ... যেহেতু উভয় ফ্রিল্যান্সার লাইভ ইভেন্ট ইন্ডাস্ট্রিতে কাজ করছিলেন, আমরা উভয়ই মূলত বেকার ছিলাম। কিছু পরিস্থিতিতে লোকেরা কেবল বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করছিল এবং এত কিছুর জন্য, আমাদের জন্য আসলে কোনও বিকল্প ছিল না।

- স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি, ওয়েলস |

দীর্ঘমেয়াদী প্রভাব

ব্যবসার মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা লকডাউনের প্রাথমিক ব্যাঘাতের পরে দীর্ঘমেয়াদী প্রভাব সম্পর্কে আমাদের জানিয়েছেন। তারা একটি অপ্রত্যাশিত পরিবেশে কাজ করার চ্যালেঞ্জগুলি সম্পর্কে কথা বলেছেন যা তাদের পরিকল্পনা করার ক্ষমতাকে প্রভাবিত করেছে।

- মহামারীর সময় ভোক্তাদের ধরণ পরিবর্তিত হওয়ায় অনেক ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপকরা ক্রমাগত হ্রাসপ্রাপ্ত রাজস্ব এবং ক্রমবর্ধমান ব্যয়ের মুখোমুখি হয়েছেন।

- ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপকরা টিকে থাকার জন্য মানিয়ে নেওয়ার চেষ্টা করেছিলেন - দূরবর্তী কাজকে সমর্থন করার জন্য বিনিয়োগ করা, তাদের ব্যবসার বৈচিত্র্য আনা এবং খরচ সর্বনিম্ন রাখার জন্য কাজ করা। এর মধ্যে প্রায়শই কর্মীদের ঘন্টা বা কর্মী সংখ্যা হ্রাস করা অন্তর্ভুক্ত ছিল।

| " | "আমাদের কি সবাইকে রিমোট কন্ট্রোলে রাখার দরকার আছে? যদি তা করি, তাহলে আমাদের অফিস থেকে বেরিয়ে আসতে হবে এবং তারপর সবাইকে ল্যাপটপ এবং বাড়ির জন্য ভিপিএন কিনতে হবে," এটা শুধু-, ভাবার মতো অনেক কিছু ছিল।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা খুচরা ব্যবসার মালিক |

| " | কোভিড আরও অনেকভাবে আঘাত করেছে যেগুলো থেকে আমরা হয়তো দুই বছরের মধ্যে সেরে উঠতে পারব। আপনি জানেন, ভোক্তারা ভিন্নভাবে কিনছেন, তারা কম দামের জিনিসপত্র কিনছেন। এখন আমাদের সম্পূর্ণ অবস্থান পরিবর্তন করতে হয়েছে, আপনি জানেন, আমরা এখন প্রতিটি গ্রাহকের কাছে কোন দামের বন্ধনীতে বিক্রি করছি ইত্যাদি। তাই, সবকিছু বদলে গেছে।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি মাঝারি উৎপাদন ব্যবসার ব্যবস্থাপক |

| " | আমরা প্রায় ১০০,০০০ পাউন্ড হারিয়েছি, এমনকি ছাঁটাই করার পরেও, এবং আমরা এখন যেখানে আছি সেখানেই আছি। এটা কখনোই পুনরুদ্ধার করা যায়নি।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা খুচরা ব্যবসার ব্যবস্থাপক |

মহামারীর কারণে চাকরির বাজার ক্ষতিগ্রস্ত হওয়ায় ব্যক্তিরা তাদের কাজ এবং আর্থিক অবস্থার উপর দীর্ঘমেয়াদী প্রভাবের কথা বর্ণনা করেছেন, যার ফলে চাকরি হারানো এবং সুযোগ সীমিত হয়েছে। অনেক ব্যক্তি আর্থিকভাবে সংগ্রামকে আয় এবং ব্যয়ের প্রাথমিক ব্যাঘাত অব্যাহত থাকার কারণ হিসাবেও বর্ণনা করেছেন।

- মহামারী অব্যাহত থাকায় অনেক ব্যক্তির কাজের সময় কমে গেছে অথবা তারা চাকরি হারিয়েছেন। যারা কাজ খুঁজছেন তারা একটি শান্ত এবং প্রতিযোগিতামূলক চাকরির বাজার বর্ণনা করেছেন যেখানে সুযোগ খুবই সীমিত এবং প্রায়শই বেকারত্ব দীর্ঘায়িত থাকে।

- যারা কর্মসংস্থান সহায়তা পেয়েছেন তারা মুখোমুখি হওয়ার পরিবর্তে অনলাইনে এটি গ্রহণের পরিবর্তনকে কম সহায়ক বলে মনে করেছেন এবং সীমিত চাকরির সুযোগ নিয়ে হতাশা অনুভব করেছেন।

- পূর্ণকালীন শিক্ষা ত্যাগকারী তরুণরা অভিজ্ঞতার অভাবে কাজ খুঁজে পাওয়া বিশেষভাবে কঠিন বলে মনে করেছিল এবং মনে করেছিল যে মহামারী তাদের ক্যারিয়ারের সম্ভাবনার উপর দীর্ঘমেয়াদী প্রভাব ফেলবে।

- অনেকেই গুরুতর আর্থিক সমস্যার সম্মুখীন হওয়ার কথা বর্ণনা করেছেন, যার মধ্যে রয়েছে যারা ইতিমধ্যেই আর্থিকভাবে দুর্বল ছিলেন এবং যারা মহামারীর শুরুতে তুলনামূলকভাবে স্থিতিশীল ছিলেন। প্রায়শই ব্যক্তিরা প্রয়োজনীয় জিনিসপত্র কিনতে হিমশিম খাচ্ছিলেন এবং জীবনযাপনের জন্য খাদ্য ব্যাংক, দাতব্য সংস্থা এবং বন্ধুবান্ধব বা পরিবারের কাছ থেকে ঋণ নেওয়ার উপর নির্ভর করতেন। ভাগ করা গল্প অনুসারে, একক পিতামাতা, প্রতিবন্ধী ব্যক্তি এবং পূর্বে বিদ্যমান স্বাস্থ্য সমস্যায় আক্রান্ত ব্যক্তিদের মতো গোষ্ঠীগুলি বিশেষভাবে মারাত্মকভাবে ক্ষতিগ্রস্ত হয়েছিল।

| " | আমার আয় নাটকীয়ভাবে কমে গেল এবং আমি বিল পরিশোধ করা অথবা ঋণ পরিশোধ না করে ঋণ নিয়ে চাপ ও উদ্বিগ্ন ছিলাম।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

সরকারি অর্থনৈতিক সহায়তা প্রকল্পের সহজলভ্যতা

অবদানকারীরা তথ্য চাওয়ার এবং কোভিড ঋণ এবং ছুটির মতো আর্থিক সহায়তার জন্য আবেদন করার কথা বিবেচনা করার মিশ্র অভিজ্ঞতা বর্ণনা করেছেন। কিছু অবদানকারীর মধ্যে হতাশা ছিল যারা মনে করেছিলেন যে যোগ্যতার মানদণ্ড প্রায়শই অন্যায্য, যার ফলে যাদের সহায়তার প্রয়োজন ছিল তারা তা থেকে বঞ্চিত ছিলেন। তবে, কিছু অবদানকারী যারা সহায়তা পেয়েছেন তারা প্রক্রিয়াটিকে যথেষ্ট সহজ বলে মনে করেছেন।

- অবদানকারীরা বিভিন্ন উপায়ে আর্থিক সহায়তা সম্পর্কে জানতে পেরেছেন, আর্থিক উপদেষ্টা, নিয়োগকর্তা, সরকারি উৎস এবং পেশাদার নেটওয়ার্ক সকলেই তথ্য বিতরণে গুরুত্বপূর্ণ ভূমিকা পালন করে।

- আর্থিক সহায়তার জন্য যোগ্যতার মানদণ্ড সম্পর্কে বোঝাপড়া এবং অভিজ্ঞতা মিশ্র ছিল, কেউ কেউ এটিকে সহজ বলে মনে করেছিলেন, আবার কেউ কেউ জটিলতা, অসঙ্গতি বা বিধানের ফাঁক নিয়ে লড়াই করেছিলেন।

- কিছু ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক হতাশ হয়েছিলেন কারণ তারা ভেবেছিলেন যে আর্থিক সহায়তা পাওয়ার ক্ষেত্রে একই ধরণের ব্যবসার সাথে সবসময় ন্যায্য আচরণ করা হয় না।

- আর্থিকভাবে অনিশ্চিত ব্যক্তিরা যখন মনে করেছিলেন যে তাদের সহায়তা পাওয়া উচিত ছিল, তখন তারা যোগ্য ছিলেন না।

- কারো কারো কাছে, সহায়তার জন্য আবেদনগুলি মূলত সহজ ছিল, যদিও অনেকেরই দীর্ঘ আবেদন প্রক্রিয়ার সাথে লড়াই করতে হয়েছিল এবং আবেদনগুলি সম্পূর্ণ করার জন্য আরও সাহায্য চাইতেন।

- সহায়তার জন্য আবেদন করার প্রধান কারণগুলি আর্থিক প্রয়োজনীয়তার উপর দৃষ্টি নিবদ্ধ করে, অন্যদিকে যারা আবেদন করেননি তারা সচেতনতার অভাব, যোগ্যতা সম্পর্কে অনিশ্চয়তা বা ঋণ নিতে অনিচ্ছার কারণে তা করেননি।

- কিছু অবদানকারী সহায়তার সময় নিয়ে খুশি ছিলেন এবং তারা কত দ্রুত এটি পেয়েছেন তা দেখে অবাক হয়েছিলেন, যখন অন্যরা, যাদের মধ্যে স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী বা শূন্য-ঘণ্টার চুক্তিতে নিযুক্ত ব্যক্তিরাও বিলম্বের সম্মুখীন হয়েছিলেন।

| " | ব্যবসাগুলির যা প্রয়োজন ছিল তার তুলনায় এটি যথেষ্ট ছিল না এবং আমার মনে হয়, সেই সময়টা একটু অন্যায় ছিল যখন আমরা মোটামুটি মাঝারি আকারের ব্যবসা ছিলাম এবং [মহামারীর] সময় আমরা প্রায় ৬০, ৭০ জনকে নিয়োগ করেছিলাম এবং তখন বাজারে একজন স্টলহোল্ডার ছিল যে স্ব-কর্মসংস্থান করত এবং নিজেরাই কাজ করত, কিন্তু তারা ঠিক আমাদের মতোই টাকা পাচ্ছিল।

- ওয়েলসে একটি ছোট ভ্রমণ এবং আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসার মালিক |

| " | আমার একটা লিমিটেড কোম্পানি আছে এবং আমি খুব সামান্য বেতন নিই। আমি বেশিরভাগ টাকা কোম্পানিতেই রাখার চেষ্টা করি। তাই, আমি যে ছুটি পেয়েছিলাম তা স্পষ্টতই আমার বেতনের উপর ভিত্তি করে ছিল কিন্তু তা আমার আয়ের প্রতিফলন ছিল না।

- স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি, স্কটল্যান্ড |

সরকারি অর্থনৈতিক সহায়তা প্রকল্পের কার্যকারিতা

বিভিন্ন ধরণের সরকারি সহায়তা প্রকল্পের উল্লেখ ছিল। ব্যবসার মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা সবচেয়ে বেশি উল্লেখ করেছেন ছুটি, 'বাউন্স ব্যাক' ঋণ এবং ব্যবসার জন্য অনুদান। ব্যক্তিদের জন্য, ছুটিও ছিল সবচেয়ে বেশি উল্লেখিত সহায়তা ব্যবস্থাগুলির মধ্যে একটি, স্ব-কর্মসংস্থান আয় সহায়তা প্রকল্প (SEISS) এর পাশাপাশি।2 এবং ইউনিভার্সাল ক্রেডিটে £২০ এর উন্নয়ন।

কারো কারো মতে, মহামারীর ফলে জরুরি চাহিদা মেটাতে তারা যে আর্থিক সহায়তা পেয়েছিল তা সহায়ক ছিল। তবে, অন্যরা মনে করেছিলেন যে উপলব্ধ সহায়তা তাদের অর্থনৈতিক চাহিদা মেটাতে যথেষ্ট ছিল না।

- কিছু অবদানকারী দেখেছেন যে এই সহায়তা তাদের চাহিদার প্রতিফলন ঘটায় এবং তাদের টিকে থাকতে সাহায্য করার ক্ষেত্রে গুরুত্বপূর্ণ ভূমিকা পালন করেছে, ছুটির মাধ্যমে অতিরিক্ত কর্মসংস্থান এড়াতে সাহায্য করেছে।

- অনেক অবদানকারী বলেছেন যে এই সহায়তা আর্থিক নিরাপত্তার অনুভূতি প্রদান করে চাপ এবং উদ্বেগ কমাতে সাহায্য করেছে।

- কিছু অবদানকারী আর্থিক সহায়তাকে সহায়ক বলে মনে করেছেন কিন্তু তাদের ব্যবসা বা পরিবারের সমস্ত খরচ মেটানোর জন্য যথেষ্ট নয়।

- অন্যরা বলেছেন যে সহায়তা অনেক কম হয়েছে, যার অর্থ তাদের জরুরি আর্থিক ব্যবস্থা গ্রহণ করতে হয়েছে যেমন ঋণ নেওয়া বা নিজেদের বা তাদের ব্যবসার জন্য ব্যক্তিগত সঞ্চয় ব্যবহার করা।

তাদের তাৎক্ষণিক চাহিদা পূরণের বাইরেও, কিছু ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা বিভিন্ন উপায়ে আর্থিক সহায়তা ব্যবহার করেছেন:

- কিছু প্রতিষ্ঠান এটিকে অভিযোজন, দক্ষতা বৃদ্ধি এবং উদ্ভাবনের জন্য ব্যবহার করেছে।

- ভিসিএসই নেতারা সম্প্রদায়গুলিকে সাহায্য চালিয়ে যাওয়ার জন্য সহায়তা ব্যবহারের উদাহরণ দিয়েছেন।

- সহায়তাকে আকস্মিক পরিস্থিতি হিসেবে বা ঋণ পরিশোধের জন্যও ব্যবহার করা হত।

মহামারী চলার সাথে সাথে, সরকার আর্থিক সহায়তায় কিছু পরিবর্তন আনে। এই পরিবর্তনগুলির মধ্যে ছিল বর্ধিত ছুটি এবং SEISS-এর মতো প্রকল্পের জন্য বর্ধিত যোগ্যতা এবং ঋণের জন্য টপ-আপ বিকল্প। এই পরিবর্তনগুলির প্রতিক্রিয়া মিশ্র ছিল। কিছু অবদানকারী এই পরিবর্তনগুলি থেকে উপকৃত হয়েছেন এবং অতিরিক্ত সহায়তাকে স্বাগত জানিয়েছেন। এমন অবদানকারীও ছিলেন যারা এই পরিবর্তনগুলিকে বিঘ্নিত এবং বিভ্রান্তিকর বলে মনে করেছিলেন, যার ফলে লোকেরা তাদের নির্ভরযোগ্য সহায়তার অ্যাক্সেস হারিয়ে ফেলেছিল।

অবদানকারীরা আমাদের সহায়তা বন্ধের অভিজ্ঞতা সম্পর্কেও বলেছেন:

- ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা বলেছেন যে বেশিরভাগ সহায়তার শেষ তারিখ নির্দিষ্ট ছিল, যা তাদের আগে থেকে পরিকল্পনা করার সুযোগ করে দেয়।

- ফার্লো ধীরে ধীরে কমানো হয়েছিল এবং কিছু ব্যক্তিকে প্রস্তুতির জন্য আগাম নোটিশ দেওয়া হয়েছিল। তবে, অন্যরা বলেছেন যে তারা খুব কম বা কোনও নোটিশ পাননি, যা অনিশ্চয়তা এবং উদ্বেগ তৈরি করেছে।

- সহায়তা বন্ধ হওয়ার পর কিছু ব্যবসা সংগ্রাম করেছে অথবা দেউলিয়া হয়ে পড়েছে, এবং ছুটির মেয়াদ শেষ হওয়ার ফলে কিছু ব্যক্তির চাকরি হারাতে হয়েছে।

| " | আমার স্বামী যখন ছুটির মেয়াদ শেষ হওয়ার কথা ছিল, তখন তার চাকরি চলে যায়। এরপর এটি বাড়ানো হয় কিন্তু ইতিমধ্যেই তাকে ছেড়ে দেওয়া হয়।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড3 |

ভবিষ্যতের জন্য প্রস্তাবিত উন্নতি

মহামারী চলাকালীন আর্থিক সহায়তা কীভাবে সংগঠিত হয়েছিল তা বিবেচনা করে, অবদানকারীরা ভবিষ্যতে কীভাবে পরিস্থিতি উন্নত করা যেতে পারে সে সম্পর্কে বেশ কয়েকটি পরামর্শ দিয়েছেন। অবদানকারীরা মহামারী থেকে কী ভালো কাজ করেছে তার উপর ভিত্তি করে তৈরি করার পরামর্শ দিয়েছে এবং কম ইতিবাচক অভিজ্ঞতার উপর ভিত্তি করে পরামর্শ দিয়েছে:

- মহামারী চলাকালীন সাফল্যের গল্প থেকে শিক্ষা নেওয়া, যার মধ্যে রয়েছে কীভাবে সহায়তা প্রায়শই সময়োপযোগী এবং অবদানকারীদের চাহিদা পূরণের জন্য পর্যাপ্ত ছিল।

| " | আমি বিশ্বাস করি ছুটির এই প্রকল্প আমার ক্যারিয়ার বাঁচিয়েছে।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

- ভবিষ্যতের মহামারীর পরিকল্পনায় আর্থিক সহায়তা কীভাবে কাজ করবে এবং যাদের প্রয়োজন তাদের কাছে ন্যায্য ও ন্যায্য প্রবেশাধিকার নিশ্চিত করবে সে সম্পর্কে বিশদ অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা।

- ইমেল, ডাক, টেলিফোন এবং মিডিয়ার মতো সরাসরি চ্যানেল ব্যবহার করে সরকার কর্তৃক সক্রিয়ভাবে আর্থিক সহায়তা ভাগ করে নেওয়ার বিষয়ে স্পষ্ট যোগাযোগ রাখা।

| " | আমার মনে হয় যা পাওয়া যাচ্ছে সে সম্পর্কে আরও ভালো যোগাযোগ, যা পাওয়া যাচ্ছে সে সম্পর্কে আরও সরাসরি যোগাযোগ।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ক্ষুদ্র ভোক্তা ও খুচরা ব্যবসার পরিচালক |

- সহজ ভাষা ব্যবহার করে তথ্য এবং নির্দেশনার জন্য একটি কেন্দ্রীভূত প্ল্যাটফর্ম তৈরি করে অ্যাক্সেসযোগ্যতা উন্নত করা।

| " | ছোট ব্যবসার জন্য, কি এমন কোন ওয়েবসাইট ছিল যেখানে আপনি যেতে পারেন এবং তথ্য বা সাহায্য পেতে সাইন আপ করতে পারেন? আমি জানি না। আমার কাছে, এটি এমন একটি ওয়ান-স্টপ শপ বলে মনে হবে যেখানে আপনি এই সমস্ত জিনিস খুঁজে পেতে পারেন ... সম্ভবত এটিই ভবিষ্যতের নির্বাণ হবে।.

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি মাঝারি আকারের পেশাদার বৈজ্ঞানিক ও প্রযুক্তিগত কার্যক্রম ব্যবসার পরিচালক |

| " | স্ব-কর্মসংস্থান অনুদান আমাকে সাহায্য করেছিল, কিন্তু সিস্টেমগুলি নেভিগেট করা কঠিন ছিল।

- এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ওয়েলস |

- কর্মীদের সহায়তা সম্পর্কিত তথ্য ভাগ করে নেওয়ার দায়িত্ব নিয়োগকর্তাদের কাছ থেকে সরে আসা।

- স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তিদের জন্য আরও ভালো সহায়তা প্রদান করা যারা মনে করেন যে তারা প্রায়শই ব্যবসা এবং ব্যক্তিদের দেওয়া আর্থিক সহায়তার ফাঁকে পড়েন।

| " | আমার মনে হয়, স্ব-কর্মসংস্থান সহায়তার একটি ন্যায্য ব্যবস্থা যা খাড়া বাঁধের ধারে ছিল না, তা আমার উদ্বেগ এবং হতাশাকে নাটকীয়ভাবে কমিয়ে দিত।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

- ঋণ এবং ব্যবসা বন্ধের মতো নেতিবাচক আর্থিক প্রভাব এড়াতে সহায়তা আরও দ্রুত, নমনীয়ভাবে এবং দীর্ঘ সময়ের জন্য বাস্তবায়ন করা।

| " | অবশেষে আমি ইউনিভার্সাল ক্রেডিট দাবি করতে সক্ষম হয়েছিলাম, কিন্তু সেই অর্থের বেশিরভাগই দুটি ব্যবসার ব্যয় মেটাতে চলে গিয়েছিল, তাই আমি দ্রুত ব্যক্তিগত ঋণে ডুবে গেলাম।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড এবং ওয়েলস |

- হঠাৎ করে বন্ধ হয়ে যাওয়ার পরিবর্তে, স্বাভাবিক কার্যক্রমে ফিরে আসা সহজ করার জন্য ধীরে ধীরে আর্থিক সহায়তা হ্রাস করা।

| " | তাই, যদি এটি আবার ঘটে, তাহলে তাদের একটি ব্যবস্থা প্রয়োজন, এ থেকে তাদের শিক্ষা নেওয়া প্রয়োজন। এবং তাদের দ্রুত জিনিসগুলি বাস্তবায়ন করতে হবে। যদি তারা আমাদের আয় করার ক্ষমতা বন্ধ করে দেয়, তাহলে তাদের তাৎক্ষণিকভাবে এটি প্রয়োজন।

– উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট নির্মাণ ব্যবসার ব্যবস্থাপনা পরিচালক |

| " | সেই ক্রান্তিকালীন পদক্ষেপ, এমনকি যদি এটি তখন প্রথম ৩-৬ মাস ধরে ৫০১TP৩T এর একটি নির্দিষ্ট হ্রাস বা অন্য কিছু ছিল ... কেবল এমন কিছু যা আপনাকে আবার এটিতে ফিরিয়ে আনবে, স্থায়ী শুরু থেকে নয়।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি কমিউনিটি ইন্টারেস্ট কোম্পানির ভিসিএসই নেতা |

- ব্যবসার জন্য আর্থিক সহায়তা এমনভাবে তৈরি করা যাতে যোগ্যতার মানদণ্ড ব্যবসার আকার, ধরণ, অবস্থান, টার্নওভার, লাভের স্তর এবং ট্রেডিং ইতিহাসের মতো বিষয়গুলি বিবেচনা করে।

| " | যেকোনো কিছু যা অর্থ-পরীক্ষিত ... আপনার কতজন কর্মী আছে, তাদের বেতন কত, আপনার মাসিক ব্যবসায়িক ব্যয় কত ... আগামী ছয় মাস বা পরবর্তী দশ মাসের জন্য আপনার আসলে কত টাকার প্রয়োজন তা দেখার জন্য ... কারণ এটি একটি কম্বল, এক-আকারের-সবকিছুর জন্য উপযুক্ত এবং এটি নয়, জীবন কখনই এমন হয় না।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা এবং খুচরা ব্যবসার মালিক |

- বিভিন্ন আর্থিক পরিস্থিতিতে অবদানকারীদের সাহায্য করতে পারে এমন আরও নমনীয় সহায়তা তৈরি করা এবং ঋণ পরিশোধের বিকল্পগুলিতে আরও নমনীয়তা প্রদান করা।

| " | যখন আপনি ঋণ নেবেন, তখন আপনার কোনও ধারণা থাকবে না যে ঋণ পরিশোধের সময়কাল কেমন হবে, পরিকল্পনা করার ক্ষেত্রে বাকি চিত্রটি কেমন হবে... তাই, স্পষ্টতই সেই সময়ে অনেক সহায়তা ছিল, কিন্তু পরে, হয়তো কিছু সাহায্য।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট লজিস্টিক ব্যবসার ব্যবস্থাপনা পরিচালক |

- VCSE এর অর্থ হলো স্বেচ্ছাসেবী, সম্প্রদায় এবং সামাজিক উদ্যোগ। এটি দাতব্য সংস্থা, সম্প্রদায় গোষ্ঠী, সামাজিক উদ্যোগ, দাতব্য সংস্থা (CIOs) এবং সম্প্রদায়ের স্বার্থ সংস্থা (CICs) এর মতো সংস্থাগুলিকে বোঝায় যারা মানুষ এবং সম্প্রদায়কে সহায়তা করার জন্য বিদ্যমান। এই সংস্থাগুলি সরকার থেকে স্বাধীন এবং অলাভজনক ভিত্তিতে পরিচালিত হয়।

- SEISS হল একটি অনুদান যা স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানপ্রাপ্ত ব্যক্তিদের তাদের তিন মাসের গড় ট্রেডিং লাভের 80% সহায়তা করে।

- ২০২০ সালের সেপ্টেম্বরে, সরকার ঘোষণা করে যে করোনাভাইরাস জব রিটেনশন স্কিম (CJRS), যা ফার্লো নামেও পরিচিত, ৩১ অক্টোবর ২০২০ তারিখে শেষ হবে এবং একটি জব সাপোর্ট স্কিম দ্বারা প্রতিস্থাপিত হবে যার জন্য নিয়োগকর্তাদের CJRS-এর অধীনে থাকা তুলনায় বেশি আর্থিক অবদান রাখতে হবে। যাইহোক, ৩১ অক্টোবর সরকার দ্বিতীয় জাতীয় লকডাউন ঘোষণা করে এবং CJRS-এর মেয়াদ বাড়িয়ে দেয়।

ভূমিকা

এই নথিতে মহামারী মোকাবেলায় সরকারের অর্থনৈতিক প্রতিক্রিয়া সম্পর্কিত মানুষের গল্প উপস্থাপন করা হয়েছে।

পটভূমি এবং লক্ষ্য

"এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স" ছিল যুক্তরাজ্য জুড়ে মানুষের জন্য মহামারী সম্পর্কে তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা UK Covid-19 Inquiry-এর সাথে ভাগ করে নেওয়ার একটি সুযোগ। শেয়ার করা প্রতিটি গল্প বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছে এবং প্রাপ্ত অন্তর্দৃষ্টিগুলিকে প্রাসঙ্গিক মডিউলের জন্য থিমযুক্ত নথিতে রূপান্তরিত করা হয়েছে। এই রেকর্ডগুলি প্রমাণ হিসাবে তদন্তে জমা দেওয়া হয়। এটি করার মাধ্যমে, তদন্তের ফলাফল এবং সুপারিশগুলি মহামারী দ্বারা প্রভাবিত ব্যক্তিদের অভিজ্ঞতা দ্বারা অবহিত করা হবে।

সরকারের অর্থনৈতিক হস্তক্ষেপের ফলে অবদানকারীরা তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা সম্পর্কে আমাদের যা বলেছেন তা এই রেকর্ডে একত্রিত করা হয়েছে।

যুক্তরাজ্যের কোভিড-১৯ ইনকোয়ারি মহামারীর বিভিন্ন দিক এবং এটি কীভাবে মানুষকে প্রভাবিত করেছে তা বিবেচনা করছে। এর অর্থ হল কিছু বিষয় অন্যান্য মডিউল রেকর্ডে অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা হবে। অতএব, এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের সাথে ভাগ করা সমস্ত অভিজ্ঞতা এই নথিতে অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা হয়নি। আপনি এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স সম্পর্কে আরও জানতে পারেন এবং ওয়েবসাইটে পূর্ববর্তী রেকর্ডগুলি পড়তে পারেন: https://covid19.public-inquiry.uk/every-story-matters

লোকেরা কীভাবে তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা ভাগ করে নিয়েছে

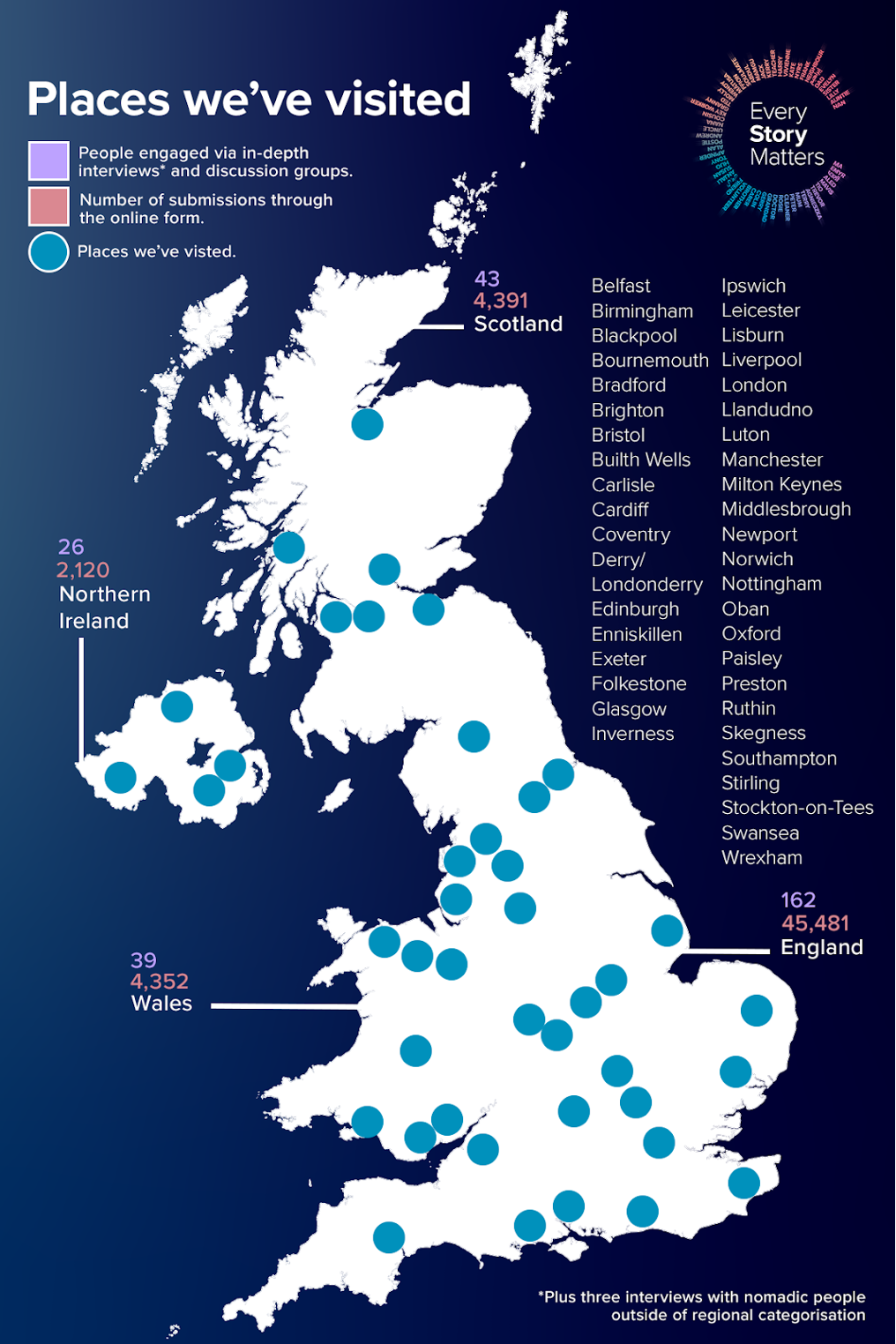

মডিউল ৯-এর জন্য আমরা বিভিন্নভাবে মানুষের গল্প সংগ্রহ করেছি। এর মধ্যে রয়েছে:

- জনসাধারণের সদস্যদের একটি সম্পূর্ণ করার জন্য আমন্ত্রণ জানানো হয়েছিল অনুসন্ধানের ওয়েবসাইটের মাধ্যমে অনলাইন ফর্ম (কাগজ ফর্মগুলি অবদানকারীদের কাছেও দেওয়া হয়েছিল এবং বিশ্লেষণে অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা হয়েছিল)। এতে তাদের মহামারী অভিজ্ঞতা সম্পর্কে তিনটি বিস্তৃত, উন্মুক্ত প্রশ্নের উত্তর দিতে বলা হয়েছিল। ফর্মটিতে তাদের সম্পর্কে পটভূমি তথ্য সংগ্রহ করার জন্য অন্যান্য প্রশ্ন জিজ্ঞাসা করা হয়েছিল (যেমন তাদের বয়স, লিঙ্গ এবং জাতিগততা)। এর ফলে আমরা বিপুল সংখ্যক মানুষের কাছ থেকে তাদের মহামারী অভিজ্ঞতা সম্পর্কে শুনতে পেরেছিলাম। অনলাইন ফর্মের প্রতিক্রিয়াগুলি বেনামে জমা দেওয়া হয়েছিল। মডিউল 9 এর জন্য, আমরা 54,809টি গল্প বিশ্লেষণ করেছি। এর মধ্যে ইংল্যান্ড থেকে 45,481টি গল্প, স্কটল্যান্ড থেকে 4,391টি, ওয়েলস থেকে 4,352টি এবং উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড থেকে 2,120টি গল্প অন্তর্ভুক্ত ছিল (অবদানকারীরা অনলাইন ফর্মে একাধিক যুক্তরাজ্যের জাতি নির্বাচন করতে সক্ষম হয়েছিলেন, তাই মোট প্রতিক্রিয়া প্রাপ্তির সংখ্যার চেয়ে বেশি হবে)। প্রতিক্রিয়াগুলি 'প্রাকৃতিক ভাষা প্রক্রিয়াকরণ' (NLP) এর মাধ্যমে বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছিল, যা মানুষের গল্পগুলিকে অর্থপূর্ণ উপায়ে সংগঠিত করতে সহায়তা করে। অ্যালগরিদমিক বিশ্লেষণের মাধ্যমে, সংগৃহীত তথ্য পদ বা বাক্যাংশের উপর ভিত্তি করে 'বিষয়'তে সংগঠিত করা হয়। গল্পগুলি আরও অন্বেষণ করার জন্য গবেষকরা এই বিষয়গুলি পর্যালোচনা করেছিলেন (আরও বিস্তারিত জানার জন্য পরিশিষ্ট দেখুন)। এই বিষয়গুলি এবং গল্পগুলি এই রেকর্ড তৈরিতে ব্যবহার করা হয়েছে।

- এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স টিম গেল ইংল্যান্ড, স্কটল্যান্ড, ওয়েলস এবং উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ডের ৪৩টি শহর ও শহরে যাতে মানুষ তাদের স্থানীয় সম্প্রদায়ের মধ্যে তাদের মহামারী অভিজ্ঞতা ব্যক্তিগতভাবে ভাগ করে নেওয়ার সুযোগ পায়। ভার্চুয়াল লিসেনিং সেশনগুলি অনলাইনেও অনুষ্ঠিত হয়েছিল, যদি সেই পদ্ধতিটি পছন্দ করা হত। আমরা অনেক দাতব্য সংস্থা এবং তৃণমূল স্তরের সম্প্রদায়ের গোষ্ঠীর সাথে কাজ করেছি যাতে মহামারী দ্বারা প্রভাবিত ব্যক্তিদের সাথে নির্দিষ্ট উপায়ে কথা বলা যায়। প্রতিটি ইভেন্টের জন্য সংক্ষিপ্ত সারসংক্ষেপ প্রতিবেদন লেখা হয়েছিল, ইভেন্ট অংশগ্রহণকারীদের সাথে ভাগ করা হয়েছিল এবং এই নথিটি অবহিত করার জন্য ব্যবহার করা হয়েছিল। সরকারের অর্থনৈতিক প্রতিক্রিয়া সম্পর্কে এই রেকর্ডের জন্য, এই মডিউলের সাথে প্রাসঙ্গিক কিছু অভিজ্ঞতার অবদান অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা হয়েছে।

- এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স কর্তৃক সামাজিক গবেষণা এবং সম্প্রদায় বিশেষজ্ঞদের একটি কনসোর্টিয়ামকে পরিচালনা করার জন্য কমিশন দেওয়া হয়েছিল গভীর সাক্ষাৎকার এবং আলোচনা গোষ্ঠী মডিউল আইনি দল কী বুঝতে চেয়েছিল তার উপর ভিত্তি করে নির্দিষ্ট গোষ্ঠীর অভিজ্ঞতা সংগ্রহ করা। ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক, স্বেচ্ছাসেবক, সম্প্রদায় এবং সামাজিক উদ্যোগ (VCSE) নেতা এবং ব্যক্তিদের সাথে সাক্ষাৎকার নেওয়া হয়েছিল, যার মধ্যে ছিল:

- বিভিন্ন আকারের এবং বিভিন্ন সেক্টরের সংগঠনের মিশ্রণ থেকে আসা ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা

- আর্থিক সমস্যায় পড়ে থাকা প্রতিষ্ঠানের ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা

- দেউলিয়া হয়ে যাওয়া প্রতিষ্ঠানের ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা (মহামারীর সময় অথবা সহায়তা বন্ধ হয়ে যাওয়ার পরে)

- মহামারী চলাকালীন বিভিন্ন কর্মসংস্থানের অভিজ্ঞতা সম্পন্ন ব্যক্তিরা

- বিভিন্ন আয়, পেশা এবং আবাসন পরিস্থিতি সহ ব্যক্তিরা

- অর্থনৈতিকভাবে দুর্বল পরিস্থিতিতে বসবাসকারী ব্যক্তি এবং বিশেষভাবে আগ্রহী গোষ্ঠী। এর মধ্যে ছিল প্রতিবন্ধী ব্যক্তি, স্বাস্থ্যগত সমস্যাযুক্ত ব্যক্তি, যাদের জন্য ইংরেজি দ্বিতীয় ভাষা এবং যারা ডিজিটালভাবে বাদ পড়েছেন।

এই সাক্ষাৎকারগুলি মডিউল ৯-এর অনুসন্ধানের মূল লাইন (KLOEs) এর উপর দৃষ্টি নিবদ্ধ করে। এই মডিউলের অস্থায়ী সুযোগ পাওয়া যাবে এখানে। ডিসেম্বর ২০২৪ থেকে এপ্রিল ২০২৫ এর মধ্যে ইংল্যান্ড, স্কটল্যান্ড, ওয়েলস এবং উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড জুড়ে মোট ২৭৩ জন এইভাবে অবদান রেখেছেন। মডিউল ৯ KLOE-এর সাথে প্রাসঙ্গিক মূল বিষয়গুলি সনাক্ত করার জন্য সমস্ত গভীর সাক্ষাৎকার এবং আলোচনা গোষ্ঠী রেকর্ড, প্রতিলিপি, কোডিং এবং বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছে। এই সাক্ষাৎকার সম্পর্কে আরও তথ্য পরিশিষ্টে পাওয়া যাবে।

অনলাইন ফর্ম, লিসেনিং ইভেন্ট এবং গবেষণা সাক্ষাৎকারের মাধ্যমে প্রতিটি যুক্তরাজ্যের দেশে তাদের গল্প ভাগ করে নেওয়া লোকের সংখ্যা নীচে দেখানো হয়েছে:

চিত্র 1: প্রতিটি গল্প যুক্তরাজ্য জুড়ে ব্যস্ততার বিষয়

গল্পের উপস্থাপনা এবং ব্যাখ্যা

এটা মনে রাখা গুরুত্বপূর্ণ যে, এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের মাধ্যমে সংগৃহীত গল্পগুলি মহামারীর প্রতি সরকারের অর্থনৈতিক প্রতিক্রিয়ার সমস্ত অভিজ্ঞতার প্রতিনিধিত্ব করে না এবং আমরা সম্ভবত এমন লোকদের কাছ থেকে শুনেছি যাদের অনুসন্ধানের সাথে ভাগ করে নেওয়ার জন্য একটি নির্দিষ্ট অভিজ্ঞতা রয়েছে, বিশেষ করে ওয়েবফর্ম এবং লিসেনিং ইভেন্টগুলিতে। মহামারীটি যুক্তরাজ্যের সকলকে বিভিন্ন উপায়ে প্রভাবিত করেছে এবং গল্পগুলি থেকে সাধারণ থিম এবং দৃষ্টিভঙ্গি উঠে আসার পরেও, আমরা যা ঘটেছিল তার প্রত্যেকের অনন্য অভিজ্ঞতার গুরুত্ব স্বীকার করি। এই রেকর্ডটির লক্ষ্য আমাদের সাথে ভাগ করা বিভিন্ন অভিজ্ঞতা প্রতিফলিত করা, ভিন্ন ভিন্ন বিবরণের সমন্বয় সাধনের চেষ্টা না করে। এমন কিছু গোষ্ঠীও ছিল যাদের গভীর সাক্ষাৎকার এবং আলোচনা গোষ্ঠীর জন্য লক্ষ্যবস্তু করা হয়েছিল যাদের কণ্ঠস্বর এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের মাধ্যমে তদন্তের জন্য শোনা গুরুত্বপূর্ণ ছিল।

শোনার অনুশীলনের অংশ হিসেবে, এই রেকর্ডের ফলাফলগুলি প্রতিনিধিত্বমূলক নয় বরং চিত্রিত। আমরা যে ব্যবসাগুলির সাথে কথা বলেছি সেগুলি আকারের দিক থেকে বৃহত্তর যুক্তরাজ্যের ব্যবসায়িক জনসংখ্যাকে ব্যাপকভাবে প্রতিফলিত করে, যেখানে ক্ষুদ্র, ক্ষুদ্র এবং মাঝারি আকারের উদ্যোগ (SMEs) বেশিরভাগ সংস্থা তৈরি করে। বৃহৎ ব্যবসাগুলিকে অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা হলেও, সামগ্রিক ব্যবসায়িক দৃশ্যপটে তাদের অনুপাত প্রতিফলিত করার জন্য তাদের সংখ্যা কম।

আমরা যে ধরণের গল্প শুনেছি তার প্রতিফলন ঘটানোর চেষ্টা করেছি, যার অর্থ হতে পারে এখানে উপস্থাপিত কিছু গল্প যুক্তরাজ্যের অন্যান্য, এমনকি অনেক লোকের অভিজ্ঞতার চেয়ে আলাদা। যেখানে সম্ভব, লোকেরা তাদের নিজস্ব ভাষায় কী ভাগ করেছে তার রেকর্ড স্থাপনে সহায়তা করার জন্য আমরা উদ্ধৃতি ব্যবহার করেছি।

মূল অধ্যায়গুলিতে কেস ইলাস্ট্রেশনের মাধ্যমে কিছু গল্প আরও গভীরভাবে অন্বেষণ করা হয়েছে। আমরা যে বিভিন্ন ধরণের অভিজ্ঞতা সম্পর্কে শুনেছি এবং মানুষের উপর এর প্রভাব কী ছিল তা তুলে ধরার জন্য এগুলি নির্বাচন করা হয়েছে। কেস ইলাস্ট্রেশনের অবদানগুলি ছদ্মনাম ব্যবহার করে (ব্যক্তির আসল নামের পরিবর্তে) বেনামী করা হয়েছে।

পুরো রেকর্ড জুড়ে, আমরা এমন ব্যক্তিদের উল্লেখ করছি যারা আমাদের সাথে কথা বলার ক্ষমতার উপর ভিত্তি করে এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের সাথে তাদের গল্প শেয়ার করেছেন। তাই আমরা 'ব্যবসায়িক মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক', 'ভিসিএসই নেতা' এবং 'ব্যক্তি' উল্লেখ করছি। যেখানে আমরা তিনটি গোষ্ঠীর কথা উল্লেখ করছি, সেখানে আমরা 'অবদানকারী' শব্দটি ব্যবহার করছি। যেখানে উপযুক্ত, আমরা তাদের সম্পর্কে আরও বর্ণনা করেছি (উদাহরণস্বরূপ, তারা স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি কিনা বা সুবিধা গ্রহণকারী কিনা) যাতে তাদের অভিজ্ঞতার প্রেক্ষাপট এবং প্রাসঙ্গিকতা ব্যাখ্যা করা যায়। আমরা যুক্তরাজ্যে সেই দেশটিকেও অন্তর্ভুক্ত করেছি যেখান থেকে অবদানকারী এসেছেন (যেখান থেকে এটি জানা যায়)। এটি প্রতিটি দেশে কী ঘটেছিল তার একটি প্রতিনিধিত্বমূলক দৃষ্টিভঙ্গি প্রদানের উদ্দেশ্যে নয়, বরং কোভিড-১৯ মহামারীর যুক্তরাজ্য জুড়ে বিভিন্ন অভিজ্ঞতা দেখানোর জন্য। গল্পগুলি ২০২২-২০২৫ সাল থেকে সংগ্রহ করা হয়েছিল এবং ২০২৫ সালে বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছিল, যার অর্থ অভিজ্ঞতাগুলি ঘটে যাওয়ার কিছু সময় পরে মনে রাখা হচ্ছে।

রেকর্ডের কাঠামো

এই নথিটি পাঠকদের ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক, ভিসিএসই নেতা এবং ব্যক্তিদের জন্য সহায়তা গ্রহণ বা না গ্রহণের প্রভাব বুঝতে সাহায্য করার জন্য তৈরি করা হয়েছে। সমস্ত অধ্যায় জুড়ে সহায়তার অভিজ্ঞতা ধারণ করে রেকর্ডটি বিষয়ভিত্তিকভাবে সাজানো হয়েছে:

- অধ্যায় ১: মহামারীর অর্থনৈতিক প্রভাব

- অধ্যায় ২: সরকারি অর্থনৈতিক সহায়তা প্রকল্পের সহজলভ্যতা

- অধ্যায় ৩: সরকারি অর্থনৈতিক সহায়তা প্রকল্পের কার্যকারিতা

- অধ্যায় ৪: ভবিষ্যতের জন্য প্রস্তাবিত উন্নতি

রেকর্ডে ব্যবহৃত পরিভাষা

নিম্নলিখিত সারণীতে মূল গোষ্ঠীগুলিকে উল্লেখ করার জন্য রেকর্ড জুড়ে ব্যবহৃত শব্দ এবং বাক্যাংশের একটি তালিকা অন্তর্ভুক্ত করা হয়েছে।

সারণী: ১ – ব্যক্তিদের জন্য ব্যবহৃত পরিভাষা

| মেয়াদ | সংজ্ঞা |

| পূর্ণকালীন কর্মচারী ব্যক্তি | এটি সেইসব ক্ষেত্রে ব্যবহৃত হয় যেখানে ব্যক্তি পূর্ণকালীন কর্মসংস্থানে থাকেন এবং নিয়োগকর্তার সাথে কাজ করেন। |

| একজন খণ্ডকালীন কর্মচারী | এটি সেইসব ক্ষেত্রে ব্যবহৃত হয় যেখানে ব্যক্তিটি কোনও নিয়োগকর্তার জন্য খণ্ডকালীন কর্মসংস্থানে থাকে। |

| স্থায়ী-মেয়াদী চুক্তি কর্মী | এটি ব্যবহার করা হয় যেখানে কথা বলা ব্যক্তির একটি নির্দিষ্ট সময়ের জন্য একজন নির্দিষ্ট-মেয়াদী চুক্তি কর্মী হিসেবে ভূমিকা ছিল। |

| শূন্য-ঘণ্টা কর্মী | এটি ব্যবহার করা হয় যেখানে ব্যক্তির শূন্য-ঘণ্টা কর্মী হিসেবে ভূমিকা থাকে, অর্থাৎ তারা এমন একজন কর্মচারী যার প্রতি সপ্তাহে কাজের ঘন্টার কোনও গ্যারান্টি নেই। তাদের নিয়োগকর্তা তাদের কোনও কাজ দিতে বাধ্য নন এবং তারা তাদের দেওয়া কোনও কাজ গ্রহণ করতে বাধ্য নন। |

| স্ব-কর্মসংস্থান (ফ্রিল্যান্স সহ) | এটি এমন একজন ব্যক্তির জন্য ব্যবহৃত হয় যিনি স্বাধীনভাবে কাজ করেন। |

| গিগ অর্থনীতির কর্মী | একজন গিগ ইকোনমি কর্মী হলেন একজন স্বাধীন ঠিকাদার বা ফ্রিল্যান্সার যিনি অনলাইন প্ল্যাটফর্ম বা অ্যাপের মাধ্যমে স্বল্পমেয়াদী চাকরি বা "গিগস" গ্রহণ করে আয় করেন। |

| অর্থনৈতিকভাবে নিষ্ক্রিয় | এটি তখন ব্যবহার করা হয় যখন কোনও ব্যক্তি বর্তমানে নিযুক্ত নন বা সক্রিয়ভাবে কর্মসংস্থান খুঁজছেন না, যার অর্থ তাদের শ্রমশক্তির অংশ হিসাবে বিবেচনা করা হয় না। |

| পরিচর্যাকারী | একজন ব্যক্তি যিনি পরিবারের কোন সদস্য, বন্ধু, অথবা প্রতিবেশী, যিনি অসুস্থ, প্রতিবন্ধী বা বয়স্ক, তাকে বিনা বেতনে সহায়তা এবং সহায়তা প্রদান করেন। |

| পেনশনভোগী | একজন ব্যক্তি যিনি অবসর গ্রহণের সময় সরকার বা প্রাক্তন নিয়োগকর্তার কাছ থেকে নিয়মিত বেতন পান। |

| বেসরকারি খাতের নিয়োগকর্তা | বেসরকারি খাতের নিয়োগকর্তারা হলেন এমন ব্যবসা বা সংস্থা যা সরকারের নয় বরং ব্যক্তি বা গোষ্ঠীর মালিকানাধীন এবং পরিচালিত। |

| দাতব্য/তৃতীয় খাতের কর্মচারী | অলাভজনক প্রতিষ্ঠানের কর্মচারী যারা জনসাধারণের কল্যাণের জন্য কাজ করে, প্রায়শই ব্যক্তিগত ব্যক্তি বা শেয়ারহোল্ডারদের জন্য মুনাফা করার পরিবর্তে সামাজিক উদ্দেশ্যে মনোনিবেশ করে। |

| সরকারি কর্মচারী | সরকার কর্তৃক অর্থায়ন ও নিয়ন্ত্রিত সরকারি বিভাগ বা সংস্থার কর্মচারী। |

| কল্যাণ সুবিধা গ্রহীতা | কল্যাণ সুবিধা প্রাপকরা হলেন সেই ব্যক্তি বা পরিবার যারা সরকারের কাছ থেকে আর্থিক সহায়তা পান, সাধারণত প্রয়োজনের ভিত্তিতে, খাদ্য, বাসস্থান এবং স্বাস্থ্যসেবার মতো মৌলিক জীবনযাত্রার ব্যয় মেটাতে সহায়তা করার জন্য। |

সারণী: ২ – ব্যবসার জন্য ব্যবহৃত পরিভাষা

| মেয়াদ | সংজ্ঞা |

| একমাত্র ব্যবসায়ী | একক ব্যবসায়ীরা হলেন স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানপ্রাপ্ত ব্যক্তি যারা তাদের ব্যবসার একমাত্র মালিক। |

| ক্ষুদ্র ব্যবসা | ১ থেকে ৯ জন কর্মচারী সহ একটি ব্যবসা। |

| ছোট ব্যবসা | ১০ থেকে ৪৯ জন কর্মচারী সহ একটি ব্যবসা |

| মাঝারি আকারের ব্যবসা | ৫০ থেকে ২৪৯ জন কর্মচারী সহ একটি ব্যবসা। |

| বৃহৎ ব্যবসা | ২৫০ জনেরও বেশি কর্মচারী সহ একটি ব্যবসা। |

| লিমিটেড কোম্পানি | একটি আইনি সত্তা যা তার মালিকদের থেকে পৃথক, অর্থাৎ এর নিজস্ব আইনি অধিকার এবং দায়িত্ব রয়েছে। শেয়ারহোল্ডারদের দায় তাদের বিনিয়োগের পরিমাণের মধ্যে সীমাবদ্ধ। |

| দানশীলতা | জনসাধারণের কল্যাণের জন্য কাজ করার উদ্দেশ্যে গঠিত একটি অলাভজনক সংস্থা, সাধারণত দাতব্য প্রতিষ্ঠানের জন্য দায়ী একটি সরকারি সংস্থার সাথে নিবন্ধিত। |

| সিআইসি | কমিউনিটি ইন্টারেস্ট কোম্পানি হল এক ধরণের সীমিত কোম্পানি যা ব্যক্তিগত শেয়ারহোল্ডারদের পরিবর্তে সম্প্রদায়ের সুবিধার জন্য কাজ করে। |

| ভিসিএসই | স্বেচ্ছাসেবী, সম্প্রদায় এবং সামাজিক উদ্যোগ ক্ষেত্রের সংগঠন। |

সারণী: ৩ – সর্বত্র ব্যবহৃত পরিভাষা

|

মেয়াদ |

সংজ্ঞা |

|---|---|

| বাউন্স ব্যাক লোন | বাউন্স ব্যাক ঋণ প্রকল্পটি মহামারী চলাকালীন ক্ষুদ্র ও মাঝারি আকারের ব্যবসাগুলিকে £2,000 থেকে £50,000 পর্যন্ত 2.5% সুদের হারে ঋণ নিতে সাহায্য করেছিল। সরকার ঋণদাতাকে 100% অর্থায়নের নিশ্চয়তা দিয়েছিল এবং প্রথম 12 মাসের জন্য ঋণের সুদ প্রদান করেছিল। |

| ব্যবসায়িক হার | দোকান, অফিস, পাব, গুদাম, কারখানা, ছুটির ভাড়া বাড়ি বা গেস্ট হাউসের মতো বেশিরভাগ অ-গার্হস্থ্য সম্পত্তির উপর ব্যবসায়িক হার ধার্য করা হয়। |

| করোনাভাইরাস ব্যবসায়িক বাধা ঋণ প্রকল্প (CBILS) | এই প্রকল্পটি ক্ষুদ্র ও মাঝারি আকারের ব্যবসাগুলিকে ৫ মিলিয়ন পাউন্ড পর্যন্ত ঋণ এবং অন্যান্য ধরণের অর্থায়ন পেতে সহায়তা করেছিল। সরকার ঋণদাতাকে ৮০১TP৩T অর্থায়নের নিশ্চয়তা দিয়েছিল এবং প্রথম ১২ মাসের জন্য সুদ এবং যেকোনো ফি প্রদান করেছিল। |

| কোভিড ক্ষুদ্র ব্যবসা অনুদান | ইংল্যান্ডের যেসব ছোট ব্যবসা প্রতিষ্ঠান খুব কম বা কোনও ব্যবসায়িক হারে অর্থ প্রদান করে না, তারা তাদের স্থানীয় কাউন্সিল থেকে এককালীন £১০,০০০ নগদ অনুদান পাওয়ার অধিকারী ছিল। |

| লভ্যাংশ | লভ্যাংশ হলো এমন একটি অর্থপ্রদান যা একটি কোম্পানি যদি লাভ করে থাকে তবে শেয়ারহোল্ডারদের দিতে পারে। |

| কর্মসংস্থান সহায়তা ভাতা (ESA) | প্রতিবন্ধী বা স্বাস্থ্যগত সমস্যাযুক্ত ব্যক্তিদের দেওয়া একটি সরকারি ভাতা যা তাদের কাজ করার ক্ষমতাকে প্রভাবিত করে। |

| সাহায্য করার জন্য বাইরে খাও | ইট আউট টু হেল্প আউট ছিল যুক্তরাজ্য সরকারের একটি প্রকল্প যা মহামারী চলাকালীন আতিথেয়তা খাতকে সহায়তা করার জন্য ২০২০ সালের আগস্ট মাসে পরিচালিত হয়েছিল। এটি সোমবার থেকে বুধবার পর্যন্ত প্রাঙ্গনে খাবার এবং নন-অ্যালকোহলযুক্ত পানীয়ের উপর ৫০১TP৩T ছাড় (প্রতি ব্যক্তি প্রতি ১০ পাউন্ড পর্যন্ত) অফার করেছিল, এবং সরকার অংশগ্রহণকারী ব্যবসাগুলিকে অর্থ প্রদান করেছিল। |

| ছুটি | করোনাভাইরাস জব রিটেনশন স্কিম নামেও পরিচিত, এটি এমন একটি স্কিম ছিল যেখানে সরকার কর্মীদের বেতনের ৮০১টিপি৩টি প্রদান করত। কর্মীরা প্রাথমিকভাবে ছুটিতে থাকাকালীন কোনও কাজ করতে পারতেন না, তবে ২০২০ সালের জুলাই থেকে আরও নমনীয় ব্যবস্থা চালু করা হয়েছিল। সময়ের সাথে সাথে সরকার কর্তৃক আওতাভুক্ত পরিমাণ হ্রাস করা হয়েছিল। |

| জবসেন্টার প্লাস | কর্ম ও পেনশন বিভাগের একটি সংস্থা যা লোকেদের কর্মসংস্থান খুঁজে পেতে এবং সুবিধাগুলি পরিচালনা করতে সহায়তা করে। |

| মাইক্রো-ব্যবসায়িক কষ্ট তহবিল (উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড) | মহামারীর কারণে নগদ প্রবাহের তাৎক্ষণিক সমস্যার সম্মুখীন হওয়া এক থেকে নয়জন কর্মচারী সহ ব্যবসাগুলিকে লক্ষ্য করে একটি অনুদান প্রকল্প। এতে যোগ্য সামাজিক উদ্যোগগুলিও অন্তর্ভুক্ত ছিল। |

| বন্ধকী ছুটি | কোভিডের সময়, সরকার বন্ধকী প্রদানকারীদের সাথে তাদের বন্ধকী পরিশোধ করতে সমস্যায় পড়াদের সহায়তা প্রদানের জন্য একমত হয়েছিল, যার ফলে কিছু লোক বন্ধকী পরিশোধ থেকে বিরতি নিতে পেরেছিল। |

| আপনার আয় অনুযায়ী অর্থ প্রদান করুন (পে) | নির্দিষ্ট ধরণের আয়ের উপর প্রদত্ত আয়করের একটি রূপ। |

| ব্যক্তিগত স্বাধীনতা প্রদান (পিআইপি) | দীর্ঘমেয়াদী শারীরিক বা মানসিক স্বাস্থ্যগত সমস্যা বা প্রতিবন্ধী ব্যক্তিদের জন্য প্রদত্ত একটি সরকারি ভাতা যাদের তাদের অবস্থার কারণে কিছু দৈনন্দিন কাজ করতে বা চলাফেরা করতে অসুবিধা হয়। |

| স্ব-কর্মসংস্থান ইনকাম সাপোর্ট স্কিম (SEISS) | একটি অনুদান যা স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তিদের তাদের তিন মাসের গড় ট্রেডিং লাভের 80% সহ সহায়তা করেছিল। মে 2020 থেকে সেপ্টেম্বর 2021 এর মধ্যে মোট পাঁচটি পর্যায়ের অনুদান পাওয়া গিয়েছিল। |

| ইউনিভার্সাল ক্রেডিট | জীবনযাত্রার খরচ বহনকারী ব্যক্তি এবং পরিবারগুলিকে সাহায্য করার জন্য একটি সরকারি অর্থপ্রদান, সাধারণত নিম্ন আয়ের ব্যক্তিদের জন্য, যারা কর্মহীন বা কাজ করতে অক্ষম। মহামারী চলাকালীন, যারা ইউনিভার্সাল ক্রেডিট পাচ্ছেন তারা তাদের পেমেন্টে সাপ্তাহিক £20 বৃদ্ধি পেতেন। |

| কাজের প্রশিক্ষক | একজন পেশাদার যিনি জবসেন্টার প্লাসের মধ্যে কাজ করেন এবং চাকরি বা ক্যারিয়ারের অগ্রগতির জন্য আগ্রহী ব্যক্তিদের সহায়তা এবং নির্দেশনা প্রদান করেন। |

১. মহামারীর অর্থনৈতিক প্রভাব

এই অধ্যায়ে অবদানকারীদের ভাগ করা গল্পের উপর ভিত্তি করে মহামারীর অর্থনৈতিক প্রভাবের রূপরেখা তুলে ধরা হয়েছে। এটি আর্থিক সহায়তা প্রদানের আগে লকডাউনের তাৎক্ষণিক অর্থনৈতিক প্রভাব অন্বেষণ করে, তারপরে মহামারীটি এগিয়ে যাওয়ার সাথে সাথে অবদানকারীদের অর্থনৈতিক ব্যাঘাতের অভিজ্ঞতা তুলে ধরে।

লকডাউনের তাৎক্ষণিক প্রভাব

অনিশ্চয়তার অনুভূতি

অবদানকারীরা ভাগ করে নিয়েছেন যে কীভাবে লকডাউন বিধিনিষেধের খবর তাদের কাজ এবং আর্থিক অবস্থার উপর প্রভাব সম্পর্কে হতবাক এবং চিন্তিত করে তুলেছে।

মহামারীর খবরে বিভিন্ন ধরণের প্রতিক্রিয়া দেখা গেছে। আমরা শুনেছি যে স্বেচ্ছাসেবী, সম্প্রদায় এবং সামাজিক উদ্যোগ (VCSEs) খাতের কিছু ব্যবসা এবং সংস্থা ইতিমধ্যেই কোভিড-১৯ ব্যাঘাত এবং কর্মক্ষেত্রে বিধিনিষেধের সম্ভাবনা দেখেছে এবং জাতীয় লকডাউন শুরু হওয়ার আগেই প্রস্তুতি শুরু করেছে। কারও কারও কাছে এর অর্থ ছিল তাদের ব্যবসা বন্ধ করে দেওয়া, আবার কেউ কেউ খোলা রাখার জন্য সংক্রমণ নিয়ন্ত্রণ ব্যবস্থা গ্রহণ করেছিলেন। একটি আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসা আমাদের জানিয়েছে যে তাদের স্থানীয় কাউন্সিল তাদের বন্ধ করতে বলেছে এবং একজন স্বাস্থ্যসেবা সহকারী জানিয়েছেন যে কীভাবে তাদের কর্মক্ষেত্র সরকারি বিধিনিষেধের আগে কোভিড-১৯ ব্যবস্থা চালু করেছিল।

| " | লকডাউনের আগে, স্কারবোরো বরো কাউন্সিল সমস্ত ছুটির আবাসন প্রাঙ্গণ, পাব এবং ক্লাবের সাথে যোগাযোগ করে আমাদের অবিলম্বে বন্ধ করার নির্দেশ দেয়, কারণ স্থানীয় হাসপাতাল কোভিড ভর্তিতে উপচে পড়েছিল।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | একজন স্বাস্থ্যসেবা সহকারী হিসেবে, কোনও জাতীয় নিয়ম কার্যকর হওয়ার আগেই আমার কর্মক্ষেত্র 'লকডাউন'-এ চলে যায়। এটি সম্পূর্ণরূপে পরামর্শমূলক ছিল। আমরা দুর্বল মানুষদের যত্ন নিতাম এবং এটি একটি যুক্তিসঙ্গত ধারণা বলে মনে হয়েছিল এবং অন্যান্য অনুরূপ প্রতিষ্ঠানগুলিও এটি করছে।

- এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

অনেকের কাছে, বিধিনিষেধের পর তাদের কর্মজীবন বা ব্যবসায়িক কার্যক্রমে উল্লেখযোগ্য পরিবর্তনের জন্য প্রস্তুত থাকা এবং মানিয়ে নেওয়ার জন্য খুব কম সতর্কতা ছিল⁴ শুরু হয়েছে। অবদানকারীরা আমাদের জানিয়েছেন যে জাতীয় লকডাউনের ঘোষণা তাদের কাছে গভীরভাবে অস্থির মনে হয়েছে। সুপারমার্কেট, ফার্মেসি এবং ব্যাংকের মতো প্রয়োজনীয় পরিষেবাগুলি ছাড়াও, সমস্ত ব্যবসা এবং ভিসিএসইগুলিকে বিধিনিষেধ শুরু হওয়ার সাথে সাথে তাদের প্রাঙ্গণ বা অফিস বন্ধ করতে হয়েছিল। ব্যবসার মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতাদের জন্য, এই বিধিনিষেধগুলি তাদের আর্থিক অবস্থার উপর কী প্রভাব ফেলবে এবং লকডাউন কতক্ষণ চলতে পারে তা নিয়ে অনিশ্চয়তা ছিল। তারা কর্মীদের কখন ফিরে আসবে তা না জেনেই তাদের কাজ থেকে বাড়ি পাঠিয়ে দিয়েছিলেন, সেই কর্মীরা প্রায়শই বেশ দ্রুত বাড়ি থেকে কাজ শুরু করেছিলেন। এই সময়টিকে ধারাবাহিকভাবে উদ্বেগ, ভয় এবং বিভ্রান্তিতে ভরা সময় হিসাবে বর্ণনা করা হয়েছিল।

| " | একজন ছোট ব্যবসার মালিক হিসেবে, আমি কীভাবে টিকে থাকব তা নিয়ে চিন্তিত ছিলাম এবং আমার ব্যবসা কতক্ষণ বন্ধ রাখতে বাধ্য হবে তা সম্পর্কে কোনও ধারণা ছিল না।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | এতে আমাদের কার্যক্রম তৎক্ষণাৎ বন্ধ হয়ে যায়। আর সেটা ছিল লকডাউনের একেবারে প্রথম দিকের দিনগুলো - আমরা নিশ্চিত ছিলাম না যে আমরা কোথায় এবং কীভাবে বাঁচব এবং এটি কেবল আমার জন্যই নয়, আমাদের সকল পরিচালকদের জন্যও অনেক উদ্বেগের কারণ হয়ে দাঁড়ায়, আমাদের কর্মীদের কী হবে, আমাদের কর্মীদের বেতন দেওয়ার ক্ষমতা কী হবে।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি দাতব্য প্রতিষ্ঠানের ভিসিএসই নেতা |

| " | তারা বলল, 'ঠিক আছে, শুক্রবার থেকে,' অথবা যাই হোক না কেন, আমার মনে হয় ২০শে মার্চ, 'সবকিছু বন্ধ করে দিতে হবে,' এবং এটি ছিল সত্যিই একটি ভীতিকর সময়।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভ্রমণ এবং আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসার পরিচালক |

ব্যবসা এবং ভিসিএসই-এর উপর তাৎক্ষণিক প্রভাব

যখন প্রথম লকডাউন ঘোষণা করা হয়েছিল, তখন অনেক ব্যবসা প্রতিষ্ঠান এবং ভিসিএসই-কে খুব কম বা কোনও সতর্কতা ছাড়াই তাদের দরজা বন্ধ করতে হয়েছিল।

কিছু ব্যবসা এবং ভিসিএসই খুব দ্রুত মানিয়ে নেওয়ার উপায় খুঁজে পেয়েছে। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, আমরা এমন সংস্থাগুলির কাছ থেকে শুনেছি যারা অফিসে অবস্থিত ছিল বা ভৌত প্রাঙ্গণ এবং কয়েক দিনের মধ্যেই দূরবর্তী কর্মক্ষেত্রে স্থানান্তরিত হয়ে সাড়া দেয়। তারা তাদের দল জুড়ে সহযোগিতা এবং সংযুক্ত থাকার জন্য ভিডিও মেসেজিংয়ের মতো ক্লাউড-ভিত্তিক সরঞ্জাম ব্যবহার করে। কারও কারও কাছে এটি ছিল ভয়ঙ্কর, বিশেষ করে স্কেল এবং জড়িত সংস্থাগুলির জন্য এটি কতটা অপরিচিত ছিল তা বিবেচনা করে।

| " | আমি NHS-এর একটি অংশে কাজ করি। মাত্র দুই দিনের মধ্যে, আমাদের ব্যবসায়িক মডেল সম্পূর্ণরূপে পুনর্গঠন করতে হয়েছিল, ৬,০০০-এরও বেশি লোকের জন্য সরঞ্জাম সংগ্রহ করতে হয়েছিল যাতে তারা বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করতে পারে এবং অজানার জন্য কার্যকরভাবে প্রস্তুত হতে পারে।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

কিছু খুচরা বিক্রেতা যারা অপ্রয়োজনীয় জিনিসপত্র (যেমন পোশাক, গৃহস্থালীর জিনিসপত্র, খেলনা এবং ইলেকট্রনিক্স) ভৌত দোকান থেকে বিক্রি করছিল তাদের তাদের ব্যবসা প্রতিষ্ঠান বন্ধ করতে হয়েছিল। তবে, কিছু খুচরা বিক্রেতা তাদের ব্যবসা অনলাইনে স্থানান্তর করে ব্যবসা চালিয়ে যেতে সক্ষম হয়েছিল। এর অর্থ প্রায়শই ওয়েবসাইট তৈরি বা আপগ্রেড করতে হত যাতে তারা অর্ডার প্রক্রিয়া করতে পারে এবং সরাসরি গ্রাহকদের কাছে পণ্য পাঠাতে পারে।

| " | আমরা অনলাইনে কিছুই করিনি, ফেসবুকের সামান্য কিছু ব্যবহার ছাড়া। কিন্তু মহামারী শুরু হওয়ার আগে পর্যন্ত কোনও অনলাইন বিক্রি হয়নি।

– ওয়েলসের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা এবং খুচরা ব্যবসার মালিক। |

আমরা ভিসিএসই-দের কাছ থেকেও শুনেছি যারা তাদের স্থানীয় সম্প্রদায়গুলিতে মুখোমুখি সহায়তা প্রদান করছিলেন (যেমন কাউন্সেলিং এবং ড্রপ-ইন পরিষেবা) এবং তারা অনলাইনেও চলে এসেছিলেন। যেখানে পরিষেবা ব্যবহারকারীরা প্রযুক্তির প্রতি আস্থা রাখতেন না বা তাদের অ্যাক্সেস ছিল না, সেখানে টেলিফোনে সহায়তা দেওয়া হত। এই ধরণের নমনীয়তা পরিষেবাগুলি অব্যাহত রাখতে সহায়তা করেছিল।

| " | কিছু ক্লায়েন্টের আইটি ছিল না, তাদের প্রযুক্তি ছিল না, অনলাইনে কাজ করার আত্মবিশ্বাস ছিল না, কিন্তু স্পষ্টতই আমরা তাদের টেলিফোনে পরামর্শ দিয়েছিলাম এবং তাদের বেশিরভাগই তা গ্রহণ করেছিলেন।

– স্কটল্যান্ডের একটি দাতব্য প্রতিষ্ঠানের ভিসিএসই নেতা |

যেসব সংস্থা সরাসরি উপস্থিত থেকে প্রয়োজনীয় পরিষেবা প্রদান করছিল (যেমন VCSE যারা জনস্বাস্থ্য-সম্পর্কিত বা সংকট সহায়তা পরিষেবা প্রদান করে) তাদের দ্রুত পদক্ষেপ নিতে হয়েছিল সুরক্ষা ব্যবস্থা বাস্তবায়নের জন্য যেমন স্ক্রিন স্থাপন, ব্যক্তিগত সুরক্ষামূলক সরঞ্জাম (PPE) প্রবর্তন, পরিষ্কার-পরিচ্ছন্নতা বৃদ্ধি এবং কর্মী এবং পরিষেবা ব্যবহারকারীদের সুরক্ষার জন্য সামাজিক দূরত্ব প্রোটোকল বাস্তবায়ন।

| " | হাত ধোয়া এবং স্যানিটাইজারের ক্ষেত্রে আমাদের অফিসে সব ধরণের বিধিনিষেধ ছিল এবং ... একে অপরের থেকে দুই মিটার দূরে থাকতে হত ... এবং আমাদের কে কোন দিন কাজ করবে তা নিয়ে দ্বিধাগ্রস্ত হতে হত যাতে আমাদের ঘরে খুব বেশি লোক না থাকে এবং এই জাতীয় জিনিস না থাকে।

– স্কটল্যান্ডের একটি দাতব্য প্রতিষ্ঠানের ভিসিএসই নেতা |

| " | আমরা প্রচুর পিপিই কিনেছি, প্রচুর সাহায্যকারী জিনিসপত্র কিনেছি, যেগুলো দরজার নীচে বেঁধে রাখা হয়েছে যাতে হাত দিয়ে নয়, পা দিয়ে দরজা খুলতে পারেন।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি সামাজিক উদ্যোগের ভিসিএসই নেতা |

তবে, অনেক ব্যবসা এবং ভিএসসিই মানিয়ে নিতে পারেনি। এর মধ্যে ভ্রমণ ও আতিথেয়তা, ইভেন্ট এবং বিনোদন ও বিনোদন খাতের অন্তর্ভুক্ত ছিল। এই খাতগুলি মানুষের সমাবেশ, ভ্রমণ বা ব্যক্তিগতভাবে যোগাযোগের উপর নির্ভরশীল ছিল এবং মহামারীর বিধিনিষেধের কারণে অনেকেই তাদের কার্যক্রম চালিয়ে যেতে অক্ষম ছিল। এই সংস্থাগুলি প্রায়শই অনলাইনে স্থানান্তর করতে বা স্বল্পমেয়াদে অন্যান্য বিকল্প নিয়ে আসতে অক্ষম ছিল।

অনেক ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা তাদের নগদ প্রবাহের উপর তাৎক্ষণিক প্রভাব দেখতে পান, কিছু ক্ষেত্রে রাতারাতি তাদের আয় দ্রুত হ্রাস পায়। বিদ্যমান কাজ তাৎক্ষণিকভাবে স্থগিত রাখা হয়, পরিষেবা বা বুকিং বাতিল করা হয় এবং কোনও নতুন অর্ডার বা বুকিং আসছে না।

| " | আচ্ছা... আমরা একটা ছোট ব্যবসা, ক্ষুদ্র ব্যবসা, তাই আমরা সপ্তাহে ৪,০০০ পাউন্ডের টার্নওভারের কথা বলছি। ২০২০ সালের মার্চ মাসের যে কোনও সময় সপ্তাহে ৪,০০০ পাউন্ড রাতারাতি শূন্য পাউন্ডে পরিণত হয়, কিছুই আসছে না, একটি পয়সাও নেই, কিছুই নেই।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা এবং খুচরা ব্যবসার মালিক |

| " | আমরা সাউথ ডেভনে একটি ছোট পাইকারি ফল এবং সবজি সরবরাহকারী। আমরা হোটেল, রেস্তোরাঁ, পাব ইত্যাদিতে সরবরাহ করি। ২০২০ সালের মার্চ মাসে রাতারাতি আমাদের সমস্ত গ্রাহক বন্ধ ছিল।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | আমি স্ব-কর্মসংস্থান করি এবং লকডাউনের প্রথম তিন সপ্তাহে £৮০,০০০ এর চুক্তি হারিয়েছি।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ওয়েলস |

| " | একটি অলাভজনক কোম্পানি হিসেবে, আমাদের খুব বেশি আর্থিক রিজার্ভ নেই। আমরা মোটামুটি হাতে-কলমে জীবনযাপন করি... আমরা 100%-এর নিজস্ব তহবিল ছিল। আমরা কোথাও থেকে তহবিলের উপর নির্ভরশীল ছিলাম না। আমরা যে অর্থ ব্যয় করেছি তা আমরা উপার্জন করেছি এবং স্পষ্টতই, যখন আপনি সেই অর্থ উপার্জনের ক্ষমতা হারিয়ে ফেলেন, তখন আপনার সমস্ত কাজ স্থগিত হয়ে যায়। তাই, এটি আমাদের কার্যক্রম অবিলম্বে বন্ধ করে দেয়।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি দাতব্য প্রতিষ্ঠানের ভিসিএসই নেতা |

কিছু ব্যবসায়িক মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপক বলেছেন যে তাদের গ্রাহকদের সেই পরিষেবাগুলির জন্য অর্থ ফেরত দিতে হবে যেগুলির জন্য ইতিমধ্যেই আগে থেকে অর্থ প্রদান করা হয়েছে। প্রায়শই, এই অর্থপ্রদানগুলি ইতিমধ্যেই পরিচালন খরচ মেটাতে ব্যবহৃত হত, কিন্তু ফেরত দেওয়ার জন্য কোথাও থেকে অর্থ খুঁজে বের করা ছাড়া তাদের আর কোনও উপায় ছিল না।

| " | আমাদের যে সকল অতিথিরা এই মরশুমের জন্য বুকিং করেছিলেন, তারা সকলেই বাতিল করছিলেন, প্রতিদিন হাজার হাজার পাউন্ডের হারে। তাই, আমাদের ক্যালেন্ডার, যা বছরের জন্য সুন্দরভাবে বুক করা হয়েছিল, দিনের বেলায় খালি হয়ে যাচ্ছিল। এবং প্রচুর পরিমাণে অনিশ্চয়তা ছিল, তাই জমা, বুকিং এবং এই জাতীয় জিনিসপত্র সম্পর্কে কী করা উচিত তা জানা খুব কঠিন ছিল।

– স্কটল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভ্রমণ এবং আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসার মালিক। |

| " | এটা বেশ স্পষ্ট ছিল এবং যদি টাকা ফেরত না দেওয়া হয় তাহলে আমাদের আদালতে নেওয়া হতে পারে... আমরা ভাবছি, 'দেখো, তোমাকে ফেরত দেওয়ার জন্য আমাদের কাছে এত টাকা নেই'।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভ্রমণ এবং আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসার পরিচালক |

ভ্রমণ এবং আতিথেয়তা খাতের ব্যবসাগুলি মারাত্মকভাবে ক্ষতিগ্রস্ত হয়েছিল এবং অনেকগুলিকে বন্ধ করতে হয়েছিল। ব্যবসার মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপকরা আমাদের জানিয়েছেন যে তাদের হোটেল, গেস্ট হাউস এবং ছুটির থাকার ব্যবস্থা ইস্টার ছুটির জন্য প্রস্তুতি নিচ্ছিল এবং দ্রুত বুকিং বাতিল করা হয়েছে। মহামারীর শুরুতে পাব বন্ধ করার অর্থ হল সমস্ত ব্যবসা বন্ধ।

| " | আমার কোম্পানি যুক্তরাজ্যে আসা ক্লায়েন্টদের দেখাশোনা করে এবং [২০২০ সালের মার্চ মাসের দিকে] আমাদের বেশ কিছু বুকিং, গ্রুপ এবং ব্যক্তি ছিল... এক সপ্তাহ বা দশ দিনের মধ্যে, সেই আসন্ন বছরের প্রতিটি বুকিং বাতিল করা হয়েছিল... প্রতিটি বুকিং।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভ্রমণ এবং আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসার পরিচালক |

| " | মহামারীর শুরুতে, আতিথেয়তা শিল্পের প্রকৃতির কারণে, বিশেষ করে খোলা আকাশের নিচে ডাইনিং বুফে, রেস্তোরাঁটি বন্ধ করতে বাধ্য হয়েছিল।

- এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | যখন কোভিড আঘাত হানে, তখন আমাদের আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসা মারাত্মকভাবে ক্ষতিগ্রস্ত হয়, বিশেষ করে বিখ্যাত 'পাবে যাবেন না' বক্তৃতার পরে।5

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

অপ্রয়োজনীয় নয় এমন হিসেবে শ্রেণীবদ্ধ খুচরা বিক্রেতা এবং পরিষেবা (উদাহরণস্বরূপ, পোশাকের দোকান, ইলেকট্রনিক্স এবং লাইফস্টাইল পণ্য বা গৃহস্থালীর উন্নতি বা সৌন্দর্য চিকিৎসা প্রদানকারী ব্যবসা) ব্যক্তিগতভাবে লেনদেন করতে অক্ষম ছিল। এর ফলে অনেক ব্যবসা স্বাভাবিকভাবে গ্রাহকদের সাথে যোগাযোগ করতে পারছিল না, ফলে তারা হঠাৎ করেই তাদের সমস্ত আয় হারিয়ে ফেলে।

প্রথম লকডাউন ঘোষণার পর কীভাবে তাদের ব্যবসা স্থবির হয়ে পড়েছিল, তা একজন সেলুন মালিক বর্ণনা করেছেন। ব্যবসা চালিয়ে যাওয়ার কোনও উপায় না থাকায়, তারা বিল এবং ওভারহেড খরচ মেটাতে তাদের পরিবারের উপর নির্ভরশীল ছিলেন। প্লাম্বিং, পেইন্টিং এবং সাজসজ্জার মতো ব্যবসার অবদানকারীদেরও তাদের কাজ বন্ধ থাকতে দেখা গেছে কারণ তারা আর মানুষের বাড়িতে যেতে পারছিলেন না।

| " | আমার একটি নতুন খুচরা ব্যবসা ছিল যা ২০২০ সালের বেশিরভাগ সময় বন্ধ করতে বা সীমিত ক্ষমতায় পরিচালনা করতে বাধ্য হয়েছিল।

- এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | লকডাউনের সময় আমার ছোট নাপিতের দোকানটি বন্ধ করতে বাধ্য হয়েছিল।

- এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | আমি একটি [বিভাগীয়] দোকানে কর্মরত ছিলাম এবং যখন মহামারীটি স্পষ্টতই আঘাত হানে, তখন আমরা লকডাউনের মধ্য দিয়ে যাই এবং আমাদের দোকানগুলি বন্ধ হয়ে যায়।

- স্কটল্যান্ডের একজন নিয়োগকর্তার কাছে পূর্ণকালীন কর্মরত ব্যক্তি |

ড্যারেনের গল্পড্যারেনের একটি ইভেন্ট এবং আতিথেয়তা ব্যবসা ছিল যা চার বছরেরও বেশি সময় ধরে প্রতিষ্ঠিত ছিল কয়েক দশক ধরে। মহামারীর আগে, ব্যবসাটি বিস্তৃত পরিসরের ক্লায়েন্টদের জন্য প্রি-বুকিং করা ইভেন্ট পরিচালনা করছিল, বৃহৎ কর্পোরেট অনুষ্ঠান থেকে শুরু করে ব্যক্তিগত বুকিং পর্যন্ত। ব্যবসাটি সমৃদ্ধ হচ্ছিল, কিন্তু প্রথম লকডাউন ঘোষণার ফলে সবকিছুই থমকে যায়। "এটা খুব একটা সুখকর অভিজ্ঞতা ছিল না। আমাদের ব্যবসা রাতারাতি কার্যত বন্ধ হয়ে যায়।" যখন বিধিনিষেধ ঘোষণা করা হয়েছিল, তখন ব্যবসাটি বছরের সবচেয়ে ব্যস্ততম সপ্তাহান্তের জন্য প্রস্তুতি নিচ্ছিল, একটি প্রধান জাতীয় ক্রীড়া ইভেন্টের জন্য। দেরিতে বাতিলের ফলে ব্যবসার পকেট থেকে হাজার হাজার পাউন্ড খাবার নষ্ট হয়ে যায়, এবং পানীয়ের মজুদও নষ্ট হয়ে যায় যা তারা স্বল্পমেয়াদে স্থানান্তর বা পুনরুদ্ধার করতে অক্ষম হয়। "ব্যক্তিগত দৃষ্টিকোণ থেকে, আমাদের কাছে ১৬,০০০ পাউন্ড মূল্যের খাবার প্রস্তুত ছিল ... আমাদের বিয়ার সেলারগুলি কানায় কানায় পূর্ণ ছিল।" কয়েকদিনের মধ্যেই তাদের অন্যান্য সমস্ত বুকিং বাতিল হয়ে যায়। ব্যবসা বন্ধ হয়ে যায়, এবং প্রথম কয়েক সপ্তাহ অনিশ্চয়তা এবং উদ্বেগের মধ্যে আচ্ছন্ন থাকে। দ্রুতই স্পষ্ট হয়ে যায় যে এই ব্যাঘাত এত তাড়াতাড়ি শেষ হবে না। ড্যারেন শেয়ার করেন যে কীভাবে শাটডাউন নিয়ন্ত্রণ হারিয়ে ফেলেছিল, যা ঘটছে তা নিয়ন্ত্রণ করার কোনও উপায় ছিল না। "সত্যিই, সত্যিই চাপের। প্রথম কয়েক সপ্তাহ, কর্মীরা প্রচুর প্রশ্ন জিজ্ঞাসা করছিল যার উত্তর আমরা দিতে পারিনি, কারণ ... আমরা জানতাম না।" স্ত্রীর সাথে বহু বছর ধরে ব্যবসা গড়ে তোলার পর, ড্যারেন সবকিছু হারানোর ঝুঁকির মুখোমুখি হয়েছিলেন। বাউন্স ব্যাক ঋণ, ওয়েলশ সরকারের অর্থনৈতিক স্থিতিস্থাপক তহবিল থেকে সহায়তা এবং ব্যবসায়িক হারে ছাড়ের পাশাপাশি, তিনি ব্যবসাটি টিকিয়ে রাখতে তার পেনশনের সুবিধাও গ্রহণ করেছিলেন। ড্যারেন তার কর্মীদের জন্য ছুটির ব্যবস্থাও ব্যবহার করেছিলেন। এই সময়ে ড্যারেনের উপর চাপ ছিল গভীর ব্যক্তিগত এবং আর্থিক উভয় দিক থেকেই; তিনি চাপটিকে অপ্রতিরোধ্য বলে বর্ণনা করেছিলেন। "মূলত, আমরা একটি রাবারের ডিঙ্গিতে ছিলাম। আমরা গর্তগুলো বন্ধ করার চেষ্টা করছিলাম এবং প্রতিদিনই একটি নতুন গর্ত হতো, জানো?" অবশেষে, ব্যবসাটি আবার চালু হতে সক্ষম হয়; তবে, বন্ধের সময় অন্য কাজ খুঁজে পাওয়ার পর ড্যারেনের সাতজন রাঁধুনির মধ্যে ছয়জন ফিরে না আসার সিদ্ধান্ত নেন। কর্মী হ্রাস এবং ক্রমবর্ধমান খরচের কারণে, তিনি ব্যবসাটি টেকসই রাখার জন্য কার্যক্রম কমিয়ে আনার সিদ্ধান্ত নেন। ব্যবসাটি আবার চালু করা চ্যালেঞ্জিং ছিল। যদিও মহামারীর আগে পরিস্থিতি এখনও আগের অবস্থায় ফিরে আসেনি, তবুও ব্যবসাটি তার পা খুঁজে পাচ্ছে এবং ড্যারেন গর্বিত যে এটি এখনও দাঁড়িয়ে আছে। |

ব্যক্তিদের উপর তাৎক্ষণিক প্রভাব

অনেক কর্মজীবী ব্যক্তির জন্য, মহামারীর প্রথম দিনগুলি ছিল তাদের চাকরি এবং কীভাবে তারা অর্থ উপার্জন করবেন তা নিয়ে বিভ্রান্তি এবং উদ্বেগের সময়।

যেখানে সম্ভব, লোকেদের বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করতে বলা হয়েছিল। ব্যক্তিরা মনে রেখেছেন যে এটি তাদের কাজের ক্ষেত্রে কেবল একটি সাময়িক ব্যাঘাত ঘটাবে। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, একজন অফিস কর্মী বলেছেন যে তাদের ল্যাপটপ সহ বাড়িতে পাঠানো হয়েছিল এবং বলা হয়েছিল যে তারা আগামী দুই সপ্তাহের জন্য দূর থেকে কাজ করবেন। ব্যক্তিরা বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করার পরিবর্তনকে একাধিক উদ্বেগের সাথে যুক্ত বলে বর্ণনা করেছেন - তাদের স্বাস্থ্য এবং তাদের প্রিয়জনদের স্বাস্থ্য, সেইসাথে মহামারী যে অর্থনৈতিক অনিশ্চয়তা নিয়ে এসেছিল।

| " | [আমাদের বলা হয়েছিল] মাত্র কয়েক সপ্তাহ পরে তুমি কাজে ফিরে আসবে, তারপর আর মাত্র কয়েক সপ্তাহ পরে তুমি ফিরে আসবে।

– স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি, স্কটল্যান্ড |

| " | যখন লকডাউন ঘোষণা করা হয়েছিল, আমরা সবাই প্রথমে দূর থেকে কাজ করছিলাম এবং সবাই কী ঘটছে তা নিয়ে অত্যন্ত উদ্বিগ্ন ছিলাম। আমাদের স্বাস্থ্য নিয়ে চিন্তিত, আমাদের প্রিয়জনদের নিয়ে চিন্তিত এবং আমাদের চাকরির নিরাপত্তা নিয়েও চিন্তিত। আমরা যে ব্যবসার জন্য কাজ করতাম তা একটি কঠিন সময়ের মধ্য দিয়ে যাচ্ছিল, তাই অবশ্যই আমরা চিন্তিত ছিলাম যে এটি ভেঙে যেতে পারে।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | হঠাৎ করেই আমি অফিসে স্থায়ীভাবে কাজ করা ছেড়ে ঘরে বসে পূর্ণকালীন কাজ করতে শুরু করলাম।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

জনসাধারণের মুখোমুখি ভূমিকায় থাকা ব্যক্তিরা, কিন্তু মনোনীত মূল কর্মী নন⁶, প্রায়শই তাদের কাজ তৎক্ষণাৎ বন্ধ হতে দেখেছি। তারা তাদের কাজ হঠাৎ বন্ধ হয়ে যাওয়ার বর্ণনা দিয়েছিলেন, যা তাদের কাছে পরিস্থিতি কতটা গুরুতর তা স্পষ্ট করে তুলেছিল। এর পরপরই এই ব্যক্তিদের মধ্যে প্রচুর ভয় এবং অনিশ্চয়তা দেখা দেয়। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, কাউন্সিলের একটি ক্রীড়া কেন্দ্রের একজন পরিচ্ছন্নতাকর্মীকে ডেকে বলা হয়েছিল যে পরের দিন তাদের কাজ অপরিহার্য বলে মনে করা হচ্ছে না বলে তিনি আসতে পারেননি। তিনি তার কাজ এবং আয় সম্পর্কে বিধিনিষেধ এবং অনিশ্চয়তার ধাক্কায় ভীত বোধ করছেন বলে বর্ণনা করেছিলেন।

| " | আমি কাউন্সিল স্পোর্টস সেন্টারে পরিষ্কার করি, তাই সেটা বন্ধ ছিল। একদিন কাজ থেকে বাড়ি ফিরতেই হঠাৎ একটা ফোন আসে, 'আর আসতে কষ্ট করো না'। হঠাৎ, ব্যাপারটা খুব, খুব গুরুতর হয়ে ওঠে... এটা ছিল অবিশ্বাস্যভাবে একাকীত্বের অভিজ্ঞতা, এবং ভীতিকর।

– স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি যিনি ইংল্যান্ডের একজন নিয়োগকর্তার কাছে খণ্ডকালীন কাজ করছিলেন। |

| " | বাড়ি ফেরার প্রায় ২ ঘন্টার মধ্যেই, আমার ম্যানেজারের কাছ থেকে ফোন আসে, 'সবকিছু লকডাউন হয়ে যাবে। তুমি ভেতরে আসতে পারবে না। আমি জানি না কী হচ্ছে, শুধু একটা ফোনের জন্য অপেক্ষা করো'। আর এটাই ছিল... এটা সত্যিই আমার মনে দাগ কেটেছিল। ফোনটা নামানোর সাথে সাথেই আমি কেঁদে ফেললাম।

– স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি যিনি ইংল্যান্ডের একজন নিয়োগকর্তার কাছে খণ্ডকালীন কাজ করছিলেন। |

লকডাউনের ফলে কিছু খাতে তাৎক্ষণিকভাবে কর্মী ছাঁটাই করা হয়েছে। জাতীয় লকডাউনের প্রত্যক্ষ প্রতিক্রিয়া এবং কিছু ব্যবসা এবং ভিসিএসই-এর আকস্মিক ও গুরুতর আয়ের ক্ষতির ফলে কীভাবে কর্মী ছাঁটাই করা হয়েছিল তার উদাহরণ আমরা শুনেছি। লকডাউনের শুরুতে অতিরিক্ত কাজ না করাকে একটি বিরক্তিকর অভিজ্ঞতা হিসেবে বর্ণনা করা হয়েছিল - বিশেষ করে কারণ ব্যক্তিরা অন্য কোথাও কাজ খুঁজে পাওয়ার ব্যাপারে আশাবাদী ছিলেন না এবং তাদের আয় হারানোর বিষয়ে চাপ অনুভব করেছিলেন।

আন্তর্জাতিক বিক্রয় ভূমিকায় কাজ করা একজন ব্যক্তিকে বরখাস্ত করা হয়েছিল কারণ ভ্রমণ সীমাবদ্ধ ছিল এবং তারা আর তাদের কাজ করতে পারছিলেন না। নির্মাণ শিল্পের আরেকজন ব্যক্তি বলেছেন যে তাদের তাৎক্ষণিকভাবে বরখাস্ত করা হয়েছিল, এটি কতটা অপ্রত্যাশিত এবং তাদের ভবিষ্যতের কাজের সম্ভাবনা সম্পর্কে তারা কতটা অনিশ্চিত বোধ করেছিলেন। মহামারীর প্রথম দিকে বন্ধ হয়ে যাওয়া একটি সেলুনে শূন্য-ঘন্টা চুক্তিতে কাজ করা একজন ব্যক্তি তাদের কাজ এবং আর্থিক অবস্থা নিয়ে চিন্তিত ছিলেন।

| " | এবং তারপর আমি আমার নিজের চাকরিও হারিয়ে ফেলি, যা শুধুমাত্র খণ্ডকালীন ছিল, কারণ সেলুনটি বন্ধ হয়ে গিয়েছিল... [মহামারীর শুরুতে]... [তারা বলেছিল] 'আমরা সেলুনটি বন্ধ করে দিচ্ছি কারণ আমরা কোনও ব্যবসা করতে পারছি না'।

- ওয়েলসের শূন্য-ঘন্টা চুক্তিভিত্তিক কর্মী ছিলেন এমন ব্যক্তি |

| " | প্রথম লকডাউনের প্রথম দিনেই আমাকে চাকরি থেকে বরখাস্ত করা হয়েছিল।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ওয়েলস |

আমরা লাইভ ইভেন্ট ইন্ডাস্ট্রিতে কাজ করা ব্যক্তিদের কাছ থেকে শুনেছি যাদের কাজ উল্লেখযোগ্যভাবে প্রভাবিত হয়েছিল। পার্টি, বিয়ে, লাইভ পারফর্মেন্স এবং খেলাধুলার মতো ব্যক্তিগত সমাবেশ আর সম্ভব নয়। ইভেন্টে কর্মরত ব্যক্তিরা জানিয়েছেন যে লকডাউন তাদের চাকরির উপর কীভাবে প্রভাব ফেলবে তা নিয়ে তারা প্রথমে বিভ্রান্ত ছিলেন। এই বিভ্রান্তি আর্থিক উদ্বেগে পরিণত হয়েছিল কারণ তারা কখন ইভেন্টগুলি পুনরায় শুরু করতে সক্ষম হবে এবং তাদের কাজ পুনরায় শুরু হতে পারে সে সম্পর্কে অনিশ্চয়তার মুখোমুখি হয়েছিলেন।

| " | আমরা কর্মক্ষেত্রে ব্যাপকভাবে প্রভাবিত হয়েছিলাম, কারণ আমরা ইভেন্ট ইন্ডাস্ট্রিতে কাজ করতাম, যা প্রায় রাতারাতি মারা গিয়েছিল।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | আমরা দুজনেই লাইভ ইভেন্ট ইন্ডাস্ট্রিতে ফ্রিল্যান্সার হিসেবে কাজ করতাম, তাই আমরা দুজনেই মূলত বেকার ছিলাম। কিছু পরিস্থিতিতে লোকেরা কেবল বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করছিল এবং এত কিছুর জন্য, আমাদের জন্য আসলে কোনও বিকল্প ছিল না।

- স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি, ওয়েলস |

| " | আমি একটি থিয়েটার এবং কনসার্ট হলের অফিসে কাজ করতাম এবং ২০২০ সালের মার্চ থেকে আমরা বন্ধ হয়ে যাই কারণ আমরা স্বাভাবিকভাবে খুলতে পারিনি এবং ২০২১ সাল পর্যন্ত পুরোপুরি খোলা হয়নি।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

চাকরি হারানো কিছু ব্যক্তি স্বল্পমেয়াদী আর্থিক সহায়তা প্রদানের মাধ্যমে রিডানডেন্সি পেমেন্ট পেয়েছেন। অন্যরা তাৎক্ষণিক এবং সম্পূর্ণ আয়ের ক্ষতির সম্মুখীন হয়েছেন।

আমরা এমন ব্যক্তিদের কাছ থেকে শুনেছি যারা মহামারীর প্রাথমিক পর্যায়ে তাদের আর্থিক পরিস্থিতির কারণে অর্থনৈতিক দুর্দশার জন্য বিশেষভাবে ঝুঁকিপূর্ণ বোধ করেছিলেন। উদাহরণগুলির মধ্যে রয়েছে:

- যাদের স্থায়ী চাকরি ছিল না। এর মধ্যে কিছু ফ্রিল্যান্স এবং স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি, গিগ ইকোনমি কর্মী এবং শূন্য-ঘন্টা চুক্তিতে থাকা ব্যক্তিরা অন্তর্ভুক্ত ছিলেন। এই কর্মীদের মধ্যে কিছু বিভিন্ন সংস্থার জন্য একাধিক চাকরিতে কাজ করেছিলেন, তাদের অব্যাহত আয় বা চাকরির সুরক্ষার কোনও অধিকার ছিল না।

- যেসব ব্যক্তিদের কোন সঞ্চয় ছিল না, অথবা যারা ইতিমধ্যেই যত্নের খরচ, অথবা কম আয়ের সাথে আর্থিকভাবে লড়াই করছিলেন। এই দলগুলির পিছনে ফিরে আসার মতো খুব কম সুরক্ষা বলয় ছিল।

- মহামারীর আগে থেকে ঋণগ্রস্ত ব্যক্তিরাউদাহরণস্বরূপ, ব্যক্তিরা বর্ণনা করেছেন যে তাদের ক্রেডিট কার্ডের ঋণ রয়েছে এবং গাড়ি এবং অন্যান্য বড় ক্রয়ের জন্য পরিশোধের পরিকল্পনাগুলি বজায় রাখতে তারা সংগ্রাম করছেন।

- রাতারাতি যাদের আয় বন্ধ হয়ে গেছে। এরা এমন কিছু চাকরি এবং সেক্টরে কর্মরত ছিলেন যেগুলো তাৎক্ষণিকভাবে বন্ধ করে কর্মীদের চাকরি ছেড়ে দিতে হয়েছিল, যার অর্থ তাদের প্রয়োজনীয় জিনিসপত্রের আয় হঠাৎ করে কমে গিয়েছিল।

এই আর্থিক সমস্যার কারণে কিছু ব্যক্তি দ্রুত অর্থের জন্য খুব চাপে পড়েন এবং চিন্তিত হয়ে পড়েন। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, একজন স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি যিনি একটি হেয়ার সেলুনে কাজ করতেন, মহামারীর শুরুতে তার চাকরি হারিয়ে ফেলেন। তিনি অর্থ নিয়ে তার উদ্বেগ এবং তার এবং তার সঙ্গীর কাছে অর্থ সঞ্চয় না থাকার হতাশার কথা বর্ণনা করেছেন। অন্য একজন লেখক তার প্রাক্তন স্বামীর কাছ থেকে আলাদা হওয়ার ফলে কীভাবে তাকে ঋণের মধ্যে ফেলে দেওয়া হয়েছিল এবং লকডাউনের প্রথম দিকে যখন তার ক্লিনার হিসেবে কাজ বন্ধ হয়ে যায় তখন তিনি যে বিশাল আর্থিক চাপ অনুভব করেছিলেন তা বর্ণনা করেছেন।

| " | আমরা চাপে ছিলাম এবং তারপর নিজেদের মধ্যে হতাশ হয়ে পড়েছিলাম যে আমাদের কাছে ভবিষ্যতের অর্থ প্রদানের জন্য সঞ্চয় নেই।

– স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি, স্কটল্যান্ড |

| " | আমাকে কাজ বন্ধ করতে হয়েছিল কারণ আমি একজন গৃহকর্মী ছিলাম এবং [ভোরে] পাবগুলিতেও পরিষ্কার করতাম। পাবগুলি বন্ধ ছিল, তাই আমার কাজ শেষ হয়ে গিয়েছিল এবং আমি ঘরগুলিও পরিষ্কার করতে পারিনি। তাই, আমি [আমার] সমস্ত টাকা হারিয়ে ফেলেছিলাম।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একজন গিগ ইকোনমি কর্মী ছিলেন এমন ব্যক্তি |

| " | আমার কোন আয় ছিল না। [আমার] আয় শেষ হয়ে গিয়েছিল, সেটা নিশ্চিত ছিল না, সেটা ছিল শূন্য ঘন্টার চুক্তি, তাই নিশ্চিত ছিল না, ন্যূনতম মজুরি। তাই, পরিবারের জন্য আমার দান শেষ হয়ে গিয়েছিল।

– স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি এবং গিগ অর্থনীতি কর্মী, উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড |

| " | আমার আক্ষরিক অর্থেই কিছুই ছিল না। কোনও আয় ছিল না। আমরা যখনই আটকে পড়লাম বা লকডাউনে ছিলাম, যেভাবেই বলি না কেন, সেদিনই আমার আয় আক্ষরিক অর্থেই বন্ধ হয়ে গেল। আগে যে সব চাকরি বুক করেছিলাম, সেগুলো আমার গ্রাহকরা আক্ষরিক অর্থেই বাতিল করে দিয়েছিলেন... হঠাৎ করেই [আমার] কোনও আয় ছিল না, কিন্তু বিলগুলো একই ছিল।

- স্ব-কর্মসংস্থানকারী ব্যক্তি, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | এটা সত্যিই কঠিন ছিল কারণ তখন ঋণ পরিশোধের চিন্তা ছিল, 'আমি কীভাবে এই খরচ মেটাবো?'

– একজন পূর্ণকালীন কর্মচারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

একজন লেখক বর্ণনা করেছেন যে মহামারীর প্রথম দিকে তিনি আর্থিকভাবে সংগ্রাম করছিলেন, যখন তিনি গর্ভবতী হওয়ার কথা জানতে পেরে একটি কারখানায় প্যাকিং করার কাজ ছেড়ে দিয়েছিলেন, কারণ তিনি কোভিড আক্রান্ত হওয়ার বিষয়ে চিন্তিত ছিলেন।

| " | আমি জানতে পারলাম যে আমি গর্ভবতী, আমি আমার জীবনের জন্য, অনাগত সন্তানের জন্য ভয় পাচ্ছিলাম, এবং কোভিড ধরা পড়ার ভয়ও পাচ্ছিলাম... যখন মহামারী এসেছিল, আমরা দুজনেই কাজ বন্ধ করে দিয়েছিলাম কারণ আমরা ভাইরাসের ভয় পেয়েছিলাম এবং তারপরে সমস্যা শুরু হয়েছিল, আমাদের কাছে [পর্যাপ্ত] টাকা ছিল না।

– একজন পূর্ণকালীন কর্মচারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

ক্যাটরিনার গল্পমহামারীর শুরুতে, ক্যাটরিনা তার সঙ্গীর সাথে ওয়েলসের গ্রামীণ একটি প্রত্যন্ত অঞ্চলে থাকতেন। তারা তার সঙ্গীর সৎ ছেলের সাথে একটি ক্যারাভানে থাকতেন। ক্যাটরিনা গ্রীষ্মের মাসগুলিতে ডেটা সংগ্রহ, গ্রাহক পরিষেবার কাজ, গিগগুলিতে আতিথেয়তা এবং অন্যান্য লাইভ ইভেন্ট সহ বিভিন্ন ব্যবসায় একাধিক খণ্ডকালীন এবং শূন্য-ঘণ্টার চুক্তিতে ছিলেন। তার চাকরি থেকে আয় বাড়ানোর জন্য, তিনি ওয়ার্কিং ট্যাক্স ক্রেডিটও পেয়েছিলেন। তিনি মহামারীর আগে তার আর্থিক পরিস্থিতি বেশ ভালো বলে বর্ণনা করেছিলেন কারণ তিনি বিভিন্ন ধরণের কাজ করেছিলেন এবং তার সঙ্গীর পূর্ণ-সময়ের আয়ের স্থিতিশীলতা ছিল। মহামারী আঘাত হানার সাথে সাথেই, স্কটল্যান্ডে তার তথ্য সংগ্রহের কাজ থেকে তাকে ছাঁটাই করা হয়। তার অন্যান্য চাকরি, যার মধ্যে খুচরা দোকানে গ্রাহক পরিষেবা পরিদর্শন এবং ইভেন্ট হসপিটালিটির কাজ অন্তর্ভুক্ত ছিল, তাও বন্ধ হয়ে যায় কারণ লকডাউন বিধিনিষেধের কারণে এই ব্যবসাগুলি বন্ধ হয়ে যায়। যখন তিনি তার চাকরি হারান, তখন জবসেন্টারের পরামর্শে তিনি ইউনিভার্সাল ক্রেডিটের জন্য আবেদন করেন। তবে, তাকে ইউনিভার্সাল ক্রেডিট প্রত্যাখ্যান করা হয় কারণ তিনি কর ছাড় পেয়েছিলেন, যা ভুলভাবে আয় হিসাবে গণনা করা হয়েছিল। এর ফলে তিনি তার স্বাভাবিক ওয়ার্কিং ট্যাক্স ক্রেডিট এবং তার আবেদন করা ইউনিভার্সাল ক্রেডিট ছাড়াই পড়ে যান। তার কর্মসংস্থান এবং সুবিধা থেকে আয় হ্রাস উল্লেখযোগ্য অনিশ্চয়তা এবং চাপ তৈরি করে। "আমি প্রায় ছয়-সাতটি ভিন্ন কোম্পানিতে কাজ করেছি, কিছু ফ্রিল্যান্স, কিছু চুক্তিবদ্ধ। এটা ছিল শূন্য-ঘণ্টার চুক্তি... স্কটল্যান্ডের কোম্পানি মহামারীর আগের দিন আমাকে ছাঁটাই করে।" তার কাজের ব্যাঘাত এবং আর্থিক সহায়তা পাবে কিনা তা নিয়ে অনিশ্চয়তার কারণে, ক্যাটরিনা তাৎক্ষণিকভাবে তার সঙ্গীর আয়ের উপর আর্থিকভাবে নির্ভরশীল হয়ে পড়েন, যার ফলে তাদের সম্পর্ক এবং জীবনযাত্রার ক্ষেত্রে উত্তেজনা দেখা দেয়। তিনি পার্সেল সংগ্রহের অস্থায়ী কাজ পেয়েছিলেন, কিন্তু এই কাজটি শারীরিকভাবে কঠিন ছিল এবং তার আয় অবিশ্বাস্য ছিল। অবশেষে তাকে তার আগের কিছু চাকরি থেকে বরখাস্ত করা হয়েছিল, তবে পরিমাণ ভিন্ন ছিল এবং সহায়তা স্বল্পস্থায়ী ছিল, যা ২০২০ সালের সেপ্টেম্বরে শেষ হয়েছিল। ক্যাটরিনার আর্থিক অবস্থা, তার টানাপোড়েনের সাথে মিলিত হয়ে, একটি চাপপূর্ণ জীবনযাপনের পরিবেশ তৈরি করেছিল। এটি তার সঙ্গীর সাথে তার সম্পর্কের উপর প্রভাব ফেলেছিল, যা অবশেষে শেষ হয়ে যায়। "আমার খরচ আমার সঙ্গীর বেতন দিয়েই মেটানো হত... এর অর্থ হল আমি জিনিসপত্র কিনতে পারতাম না। আমি তার উপর নির্ভরশীল ছিলাম, যা আমি পছন্দ করতাম না... তাই, তার উপর নির্ভর করতে হওয়া আমাদের সম্পর্কের উপর আর্থিকভাবে প্রভাব ফেলেছিল।" মহামারী চলতে থাকলে, ক্যাটরিনা ইভেন্ট সেক্টরে (যে ক্ষেত্রটিতে তিনি কাজ করতে চেয়েছিলেন) নিয়মিত কাজ খুঁজে পেতে লড়াই করতে থাকেন। অবশেষে তিনি আরও স্থিতিশীল ক্যারিয়ারের সন্ধান করেন, ২০২১ সালের এপ্রিলে বিদ্যুৎ মিটার রিডার হয়ে ওঠেন। |

মহামারীর দীর্ঘমেয়াদী অর্থনৈতিক পরিণতি

মহামারীর অর্থনৈতিক প্রভাব প্রাথমিক লকডাউনের বাইরেও বিস্তৃত হয়েছিল, যার ফলে ব্যবসা, ভিসিএসই এবং ব্যক্তিদের জন্য একটি অস্থির এবং অপ্রত্যাশিত পরিবেশ তৈরি হয়েছিল। চাহিদার ওঠানামা, ক্রমবর্ধমান ব্যয় এবং বারবার লকডাউনের অনিশ্চয়তা চলমান চ্যালেঞ্জগুলি উপস্থাপন করেছিল। কিছু ব্যবসায় চাহিদা হ্রাস অব্যাহত রেখেছে, আবার কিছু ব্যবসায় আশ্চর্যজনকভাবে বৃদ্ধি পেয়েছে। এর সবই ব্যবসায়িক কার্যক্রম, কর্মসংস্থান, শ্রমবাজার এবং চাকরির সন্ধান এবং মানুষের ব্যক্তিগত আর্থিক পরিস্থিতির উপর প্রভাব ফেলেছে।

ব্যবসা এবং ভিসিএসই কীভাবে নতুন অর্থনৈতিক পরিস্থিতির সাথে খাপ খাইয়ে নিয়েছে

ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা মহামারীতে নতুন বাস্তবতার সাথে খাপ খাইয়ে নেওয়ার বিভিন্ন উপায় নিয়ে আলোচনা করেছেন।

দূরবর্তী কাজকে সমর্থন করার জন্য বিনিয়োগ ছিল একটি মূল লক্ষ্য। কিছু ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতারা মহামারী চলাকালীন দূরবর্তী কর্মক্ষেত্রে স্থানান্তরের বর্ধিত খরচ সম্পর্কে কথা বলেছেন। তারা আমাদের বলেছেন যে কীভাবে তাদের প্রায়শই সরঞ্জাম কিনতে হয়েছিল বা নতুন সিস্টেম স্থাপন করতে হয়েছিল এবং কর্মীদের কার্যকরভাবে কাজ চালিয়ে যেতে সক্ষম করার জন্য স্বল্প সময়ের নোটিশে তাদের রোলআউট পরিচালনা করতে হয়েছিল। তারা দ্রুত দূরবর্তী কর্মক্ষেত্রে খাপ খাইয়ে নেওয়ার ক্ষেত্রে যে আর্থিক এবং পরিচালনাগত চাপের মুখোমুখি হয়েছিল তা স্মরণ করেছেন। মহামারীর প্রথম সপ্তাহগুলিতে এর ফলে যে উল্লেখযোগ্য চাপ এবং চাপ তৈরি হয়েছিল তা আমরা শুনেছি।

| " | হঠাৎ করেই, রাতারাতি আমাদের সবাইকে বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করার জন্য সেট আপ করতে হয়েছিল, তাই এটি সম্পূর্ণ নতুন ছিল ... আমাদের অফিসে কেবল ডেস্কটপ ছিল, যা স্পষ্টতই আপনি বাড়িতে বহন করতে পারবেন না, সহজে নয়। সুতরাং, এটি [একটি] প্রাথমিক খরচ ছিল কারণ আমাদের কেবল সবার জন্য একটি নতুন ল্যাপটপ কিনতে হয়েছিল, এটি সেট আপ করতে হয়েছিল, এবং তারপরে কেবল কীভাবে আমরা এটি করব তা নির্ধারণ করতে হয়েছিল কারণ আমরা আগে কখনও এটি করিনি।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট আর্থিক ও পেশাদার পরিষেবা ব্যবসার অফিস ব্যবস্থাপক |

| " | অনেক অ্যাডমিন স্টাফ - তারা ডেস্কটপে কাজ করে। আমরা সবসময় এভাবেই কাজ করে আসছি এবং স্পষ্টতই, তাদের জন্য আমাদের প্রচুর হার্ডওয়্যার কিনতে হয়েছিল। আমাদের সবকিছু পরীক্ষা করে দেখতে হয়েছিল। সবকিছু সেট আপ করতে হয়েছিল। তাই, আইটি বিভাগ প্রথম কয়েক সপ্তাহ ধরে তাদের পা থেকে বেরিয়ে গিয়েছিল। আপনি জানেন এবং এর সাথে একটি খরচও যুক্ত ছিল ... যা এমন একটি খরচ যা আমরা আসলে কল্পনাও করিনি।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি মাঝারি আকারের পেশাদার, বৈজ্ঞানিক এবং প্রযুক্তিগত কার্যকলাপ ব্যবসার অফিস ম্যানেজার। |

কিছু ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতাদের জন্যও বৈচিত্র্যকরণের উপর জোর দেওয়া হয়েছিল। মহামারীর প্রতিক্রিয়ায় তারা প্রায়শই তাদের ব্যবসাকে আরও বৈচিত্র্যময় বা আরও বৈচিত্র্যময় করার সিদ্ধান্ত নিয়েছিল যাতে তারা আর্থিকভাবে আরও স্থিতিশীল হয়ে ওঠে। এটি সাধারণত তাদের সামগ্রিক ব্যবসায়িক কৌশলের অংশ ছিল, তারা সরকারের কাছ থেকে আর্থিক সহায়তা পেত কিনা তা নির্বিশেষে। আমরা তাদের কাছ থেকেও শুনেছি যারা আর্থিকভাবে স্থিতিশীল ছিলেন কারণ তাদের ব্যবসা ইতিমধ্যেই বৈচিত্র্যময় ছিল। এর অর্থ হল তারা মহামারী চলাকালীন কিছু নির্দিষ্ট কার্যক্রমে ফোন করতে সক্ষম হয়েছিল। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, একটি টেলিকম ব্যবসা মহামারীর প্রথম বছরে বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করা আরও বেশি লোকের বর্ধিত চাহিদা মেটাতে ওয়াই-ফাই ইনস্টলেশনের উপর দৃষ্টি নিবদ্ধ করেছিল।

| " | ব্যবসার কিছু ক্ষেত্র অবশ্য শান্ত হয়ে গিয়েছিল, কিন্তু সেই সময়ে ব্যবসার অন্যান্য ক্ষেত্রগুলি স্পষ্টতই অনেক বৃদ্ধি পেয়েছিল। সুতরাং, সামগ্রিকভাবে, একটি কোম্পানি হিসেবে আমরা ছিলাম, কারণ আমাদের কাজের ধরণ বেশ বৈচিত্র্যময়, তবুও আমরা আসলে সত্যিই লাভজনক ছিলাম।

– ওয়েলসের একটি বৃহৎ আর্থিক ও পেশাদার পরিষেবা ব্যবসার সিনিয়র ফিনান্স ম্যানেজার |

আমরা আরও শুনেছি কিভাবে কিছু ব্যবসার চাহিদা এবং বিক্রয় বৃদ্ধি পেয়েছে। মহামারী চলাকালীন কিছু ভোগ্যপণ্য জনপ্রিয় হয়ে ওঠে - যেমন ফোন, অথবা ঘরে বসে হট টাবের মতো অবসর কার্যক্রম - এবং এই খাতের ব্যবসাগুলি আয় বৃদ্ধি পেয়েছে।

| " | আমি বলব যে তথ্য থেকে আমরা দেখতে পাচ্ছি যে মহামারীর সময় বিক্রি বেড়েছে। তাই, অনেক মানুষ কোনও কারণে বেশি ফোন কিনছিলেন। তারা আসলে আরও বেশি ফোন সংযোগ করছিলেন।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি মাঝারি আকারের উৎপাদন ব্যবসার ব্যবসায়িক ব্যবস্থাপক |

ম্যাথিউর গল্পম্যাথিউ একটি ছোট ব্যবসার বিক্রয় পরিচালক যারা হট টাব তৈরি করে। মহামারীর সময়, ব্যবসাটি চাহিদার তীব্র বৃদ্ধির সাথে খাপ খাইয়ে নিতে সক্ষম হয়েছিল। মানুষ যখন ঘরে বেশি সময় কাটাত এবং তাদের বাইরের জায়গার আরও ভাল ব্যবহার করার চেষ্টা করত, তখন হট টাবগুলি একটি চাহিদাপূর্ণ পণ্য হয়ে ওঠে। "এটা ব্যবসার জন্য অসাধারণ ছিল - আমরা কেবল [হট টাব] যথেষ্ট দ্রুত তৈরি করতে পারিনি।" অনলাইনে বিক্রি শুরু হওয়ায় ব্যবসাটি এই বর্ধিত চাহিদা মেটাতে বেশ ভালো অবস্থানে ছিল। এর অর্থ হল, ম্যাথিউর দল আগ্রহ বাড়লে দ্রুত সাড়া দিতে পারত এবং লকডাউনের সময়ও অর্ডার নেওয়া চালিয়ে যেতে পারত। "পরিসংখ্যানগুলি জ্যোতির্বিদ্যাগত, আপনি জানেন, যারা আপনার ওয়েবসাইটে আসছেন এবং যারা জিজ্ঞাসা করছেন তারা ছাদের উপরে উঠে এসেছেন, এটি নজিরবিহীন।" চাহিদার দ্রুত বৃদ্ধি মেটানোর অর্থ হল আরও কর্মী নিয়োগ করা, স্টোরেজ স্পেস বাড়ানো এবং ডেলিভারি ক্ষমতা বৃদ্ধি করা। ম্যাথিউ ব্যাখ্যা করেছিলেন যে তারা ইতিমধ্যে যা তৈরি করেছে তার উপর ভিত্তি করে দ্রুত কাজ বৃদ্ধি করা সম্ভব হয়েছে। "আমাদের সবকিছুর আরও বেশি প্রয়োজন ছিল, আমাদের আরও লোকের প্রয়োজন ছিল ... আরও জায়গা ... [হট টাব] সরবরাহ করার জন্য আরও ট্রাক, আমাদের আরও সবকিছুর প্রয়োজন ছিল। এবং তারপরে এটি করার জন্য দ্রুত ব্যবসাটি বাড়াতে হয়েছিল।" এই সময়ের কথা চিন্তা করে, ম্যাথিউ দ্রুত বড় পরিবর্তন আনার চাপ বর্ণনা করেছিলেন, কিন্তু এমন একটি সময় হিসেবেও যা দেখিয়েছিল যে ব্যবসা কতটা নিতে পারে। |

ব্যবসায়িক মালিক, ব্যবস্থাপক এবং ভিসিএসই নেতাদের ভূমিকাও পরিবর্তিত হয়েছে। ক্ষুদ্র ও ক্ষুদ্র ব্যবসার মালিকরা বর্ণনা করেছেন যে কীভাবে তাদের প্রায়শই আরও বেশি দায়িত্ব গ্রহণ করতে হয় এবং প্রশাসনিক কাজ বা বিতরণের ক্ষেত্রে বৈচিত্র্য আনতে হয় - যাতে কম লোকের সাথে তাদের ব্যবসা চালানো যায়। তারা প্রতিফলিত করেছেন যে কীভাবে এই অতিরিক্ত কাজের কারণে তারা প্রায়শই ক্লান্ত হয়ে পড়েন এবং পরিবারের সদস্যদের সাথে উত্তেজনার সৃষ্টি করেন কারণ তারা দীর্ঘ সময় ধরে কাজ করেন।

| " | তুমি শুধু কোম্পানির পরিচালকই নও, তুমি সার্ভিস রিসেপশনিস্ট, গাড়ি পরিষ্কারকও, যন্ত্রাংশ কিনতে যাওয়া এবং সমস্ত লজিস্টিকস করা, লোকেদের বুকিং করা, লোকে আসছে কিনা তা নিশ্চিত করার জন্য ফোন করা এবং সবকিছুর সমন্বয় করা, সত্যিই, খুব কঠিন ছিল।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ক্ষুদ্র পরিবহন ব্যবসার পরিচালক যা দেউলিয়া হয়ে যায়। |

কিছু ব্যবসা প্রতিষ্ঠান ছিল যাদের তাদের দামে অথবা গ্রাহকদের কাছ থেকে অর্থপ্রদান পরিচালনার পদ্ধতিতে পরিবর্তন আনতে হয়েছিল। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, কিছু ব্যবসা প্রতিযোগিতামূলক থাকার জন্য চার্জ বিলম্বিত করে বা দাম কমিয়ে চাহিদা বজায় রাখার এবং ক্লায়েন্টদের ধরে রাখার চেষ্টা করেছিল। এর ফলে ব্যবসাগুলির জন্য আরও আর্থিক চ্যালেঞ্জ তৈরি হয়, যা তাদের নগদ প্রবাহ এবং লাভজনকতার উপর প্রভাব ফেলে।

| " | আমরা হয়তো তিন মাসের জন্য তাদের অর্ধেক দামে ভাড়া দেব। অথবা হয়তো চার মাসের জন্য ভাড়ামুক্ত থাকার পর তারা সেই ভাড়া পরিশোধ করবে, যা বিলম্বিত অর্থ। তাই, তারা আপাতত ভাড়ামুক্ত থাকবে, কিন্তু চুক্তির শেষে তাদের তা পরিশোধ করতে হবে। তাই, তাদের নগদ প্রবাহে সহায়তা করার জন্য এই মুহূর্তে তাদের কিছু দিতে হচ্ছে না।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট রিয়েল এস্টেট ব্যবসার পরিচালক |

| " | যেখানে সাধারণত মানুষ দুটি ভিন্ন কোম্পানি থেকে দুটি কোট চাইত, এখন তারা চার এবং পাঁচটি চাইছে, কারণ তারা জানত যে মানুষ [ব্যবসায় এবং ব্যবসায়ীরা] কাজের জন্য মরিয়া। লোকেরা তাদের দাম কমিয়ে দিত, যা সত্যিই কঠিন ছিল, কারণ স্পষ্টতই আপনি বিনামূল্যে কাজ করতে পারবেন না, কিন্তু তখন মনে হত, আপনি কি অল্প টাকার জন্য কাজ করেন, নাকি আপনি একেবারেই কাজ করেন না? তাহলে, এটা কঠিন ছিল।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ক্ষুদ্র ভোক্তা এবং খুচরা ব্যবসার পরিচালক যা দেউলিয়া হয়ে পড়েছিল। |

ব্যবসা এবং ভিসিএসই কীভাবে তাদের পরিচালনার ধরণ পরিবর্তন করে খরচ কমাতে আরও এগিয়ে গেছে তার উদাহরণ আমরা শুনেছি। এর মধ্যে ছিল অফিসের জায়গার খরচ সাশ্রয় করা, মৌসুমী কর্মীদের সংখ্যা কমানো এবং কর্মচারীদের বোনাস ও বেতন বৃদ্ধি বন্ধ করা।

| " | ভ্রমণ খরচ... কর্মীদের জন্য কিছু সুবিধা, ক্রিসমাস বা বছরের শেষের পার্টিও বাতিল করা হয়েছিল, যা হ্যাঁ, কর্মীদের জন্য খুব একটা ভালো ছিল না।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি বৃহৎ খাদ্য ও পানীয় ব্যবসার অর্থ পরিচালক |

| " | আমার নিয়োগকর্তা [কোভিড] কে অজুহাত হিসেবে ব্যবহার করেছিলেন মুদ্রাস্ফীতির কারণে আমাদের বেতন না বাড়ানোর জন্য এবং আমাদের ক্রিসমাস বোনাস না দেওয়ার জন্য।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড। |

কিছু ব্যবসা এবং ভিসিএসই প্রতিষ্ঠানের জন্য, দূরবর্তীভাবে কাজ করার দিকে ঝুঁকে পড়ার অর্থ হল তাদের আর একই পরিমাণ অফিস স্থানের প্রয়োজন ছিল না। আয় হ্রাস এবং পরিষেবা প্রদানের পদ্ধতিতে পরিবর্তনের প্রতিক্রিয়ায় খরচ কমানোর জন্য প্রাঙ্গণ কমানো একটি ব্যবহারিক উপায় হয়ে ওঠে। কিছু ক্ষেত্রে, এটি ভেসে থাকার জন্য অপরিহার্য ছিল; অন্য ক্ষেত্রে, এটি ছিল নতুন কাজের ধরণগুলির সাথে খাপ খাইয়ে নেওয়ার এবং সম্ভব হলে ওভারহেড কমানোর একটি উপায়।

| " | আমরা ছয়জনের অফিসে ডাউনগ্রেড করেছিলাম এবং তারপর আরও ডাউনগ্রেড করে আবার আপগ্রেড করার আগে। কিন্তু আমরা কেবল ক্রমাগত যেখানে সম্ভব সেখানে নজরদারি করার এবং যেখানে সম্ভব খরচ কমানোর চেষ্টা করছিলাম।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা এবং খুচরা ব্যবসার মালিক। |

| " | আমরাও আকার কমিয়েছি, আমাদের পরিচালন খরচ সত্যিই কমিয়েছি। আমরা ভাড়া এবং এর সাথে সম্পর্কিত সবকিছুর জন্য প্রতি চতুর্থাংশে প্রায় £200,000 খরচ করতাম এবং এখন আমরা মাসে £8,000 এরও কম খরচ করছি।

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট পেশাদার, বৈজ্ঞানিক এবং প্রযুক্তিগত কার্যক্রম ব্যবসার অপারেশন ম্যানেজার |

যদিও এই সঞ্চয়গুলি সাধারণত হারানো আয়ের ক্ষতিপূরণ দেওয়ার জন্য যথেষ্ট ছিল না, তবুও কিছু সংস্থার আর্থিক চাপ কমাতে তারা সাহায্য করেছিল।

কর্মসংস্থানে পরিবর্তন: ব্যবসায়িক দৃষ্টিকোণ

যেকোনো ধরণের সরকারি সহায়তা - যেমন ছুটি - চালু হওয়ার আগে, চাহিদা কমে যাওয়া এবং রাজস্ব হ্রাসের জন্য নিয়োগকর্তাদের তাদের কর্মী সংখ্যা কমানোর সিদ্ধান্ত নিতে হয়েছিল। ব্যবসায়িক মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপকরা এর ফলে তাদের উপর যে মানসিক আঘাত নেমেছিল তা বর্ণনা করেছেন, কারণ তাদের কর্মীদের বলতে হয়েছিল যে তারা আর তাদের কাজে লাগাতে পারছেন না। তারা জোর দিয়ে বলেছেন যে কর্মীদের ছাড়িয়ে দেওয়া কতটা কঠিন সিদ্ধান্ত ছিল। কেউ কেউ বলেছেন যে তারা যতদিন সম্ভব তাদের কর্মীদের ধরে রাখার চেষ্টা করেছেন, কিন্তু অবশেষে তাদের ছেড়ে দেওয়া ছাড়া আর কোনও উপায় ছিল না।

| " | এক ভয়াবহ দিন, আমাকে আমার কর্মীদের 80%-তে ফোন করে বলতে হয়েছিল যে তাদের আর চাকরি নেই বলে তাদের ছাঁটাই করতে হবে। আর আমি কেঁদেছিলাম, সারা রাত ঘুমাইনি, আমি এতটাই বিরক্ত ছিলাম। আমার কাছে এমন কিছু লোক ছিল যারা সাত-আট বছর ধরে আমার জন্য কাজ করেছিল, যাদের আমাকে বলতে হয়েছিল, 'আমি খুবই দুঃখিত, আমি আক্ষরিক অর্থেই আপনাকে আর বেতন দিতে পারছি না কারণ আমাদের কোনও ব্যবসা নেই।'

- ইংল্যান্ডের একটি ছোট ভোক্তা খুচরা বিক্রেতার মালিক |

| " | কিন্তু এটা এমন এক পর্যায়ে পৌঁছেছিল যেখানে তারা জানতে পেরেছিল এবং আমাকে খোলামেলা এবং সৎ হতে হয়েছিল এবং তাদের বলতে হয়েছিল, 'তুমি জানো, আমি এটা চিরকাল ধরে রাখতে পারব না।'

– ইংল্যান্ডে একটি ছোট পেশাদার, বৈজ্ঞানিক এবং প্রযুক্তিগত কার্যকলাপ ব্যবসায়ের অংশীদার |

| " | এটি একটি অত্যন্ত চাপপূর্ণ সময় ছিল যা এই সময়ে কর্মীদের অতিরিক্ত করা এবং পুনর্গঠন করেও সমাধান করা যায়নি।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

উদাহরণস্বরূপ, একটি উৎপাদন ও প্রকৌশল ব্যবসা মহামারী চলাকালীন সময়ে কর্মী ছাঁটাই করতে বাধ্য হয়েছিল কারণ তারা পূর্বে প্রদত্ত কিছু চুক্তি হারিয়েছিল। যেসব কর্মচারীকে বরখাস্ত করা হয়েছিল তাদের মধ্যে কিছুরই বাকি থাকা চুক্তির জন্য বা এখনও ব্যবহৃত যন্ত্রপাতি পরিচালনার জন্য প্রয়োজনীয় দক্ষতা ছিল না। কম কর্মী নিয়ে এবং বাকি দলকে তাদের দৈনন্দিন কাজের পাশাপাশি অতিরিক্ত দায়িত্ব নেওয়ার মাধ্যমে ব্যবসাটি চলতে থাকে। বরখাস্ত করা একটি স্বল্পমেয়াদী ব্যবস্থা ছিল যা মহামারী চলাকালীন ব্যবসাটিকে টিকিয়ে রাখতে সাহায্য করেছিল। তারপর থেকে, ব্যবসাটিকে পুনর্নির্মাণ এবং নিয়োগ করতে হয়েছে যাতে এটি আবার পূর্ণ ক্ষমতায় পরিচালিত হতে পারে।

| " | স্পষ্টতই, আমাদের কিছু লোককে ছাঁটাই করতে হয়েছে... তারা [যাদের ছাঁটাই করা হয়েছিল] যে কাজগুলি করছিল, কিছু লোক যে ধরণের যন্ত্রপাতি ব্যবহার করা হচ্ছিল তাতে দক্ষ ছিল না। [যাদের ছাঁটাই করা হয়েছিল] তাদের কিছু দক্ষতা [মহামারী চলাকালীন] আমরা যে বিভিন্ন চুক্তি অর্জন করেছিলাম এবং হারিয়েছিলাম তার জন্য ব্যবহার করা হয়েছিল।

– ইংল্যান্ডের একটি মাঝারি আকারের লজিস্টিক ব্যবসার মালিক। |

অন্যদিকে, কিছু ব্যবসায়িক মালিক এবং ব্যবস্থাপকরা মহামারী চলাকালীন আরও কর্মী নিয়োগ করেছিলেন, প্রায়শই বর্ধিত চাহিদার কারণেউদাহরণস্বরূপ, একটি ব্যবসা প্রতিষ্ঠান যারা কাজের বাইরে জিপি এবং হাসপাতালের সহায়তা প্রদান করে, তাদের পরিষেবার ক্রমবর্ধমান চাহিদা মেটাতে ৬০ জন অস্থায়ী কর্মী নিয়োগ করে।

কর্মসংস্থানে পরিবর্তন: ব্যক্তিগত দৃষ্টিভঙ্গি

কিছু স্থায়ী কর্মচারীর কাজের সময় কমিয়ে দেওয়া হয়েছিল যাতে তাদের নিয়োগকর্তা খরচ কমাতে পারেন, যা সাধারণত তাদের আয় কমিয়ে দেয়। একটি নির্দিষ্ট উদাহরণ হল একজন বেসরকারি বাস চালক যিনি আমাদের বলেছিলেন যে তাদের ব্যবসার চালকরা কম ঘন্টা কাজ করার এবং কম অর্থ উপার্জনের সিদ্ধান্ত নিয়েছিলেন যাতে তারা সকলেই তাদের চাকরি ধরে রাখতে পারেন।

| " | যেহেতু আমি যে কোম্পানিতে কাজ করছিলাম তা একটি ছোট, স্বাধীন [কোম্পানি] ছিল, তাই আমরা সবাই একমত হয়েছিলাম যে আমরা কাজ ভাগ করে নেব... লোকেদের এখনও ভ্রমণ করতে হচ্ছিল। তাই, আমি আর্থিকভাবে ক্ষতিগ্রস্ত হচ্ছিলাম, কিন্তু অনেক লোক ছিল যাদের অবস্থা আমার চেয়ে অনেক খারাপ ছিল... আমি ২৫ ঘন্টা কাজ করেছি, তাই সবাই একটি শিফট পেয়েছি। এটা ছড়িয়ে দেওয়া ন্যায্য। আমি ৩ দিন কাজ করব এবং আমার সহকর্মী ৩ দিন কাজ করবে।

– একজন পূর্ণকালীন কর্মচারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | [আমি] একটি পেট্রোল পাম্পে কাজ করতাম... [লকডাউনের] পর, তারা আমার কাজের সময় সাত দিন থেকে কমিয়ে দুই দিন করে দেয় কারণ তারা বলেছিল যে অর্থনীতি ভেঙে পড়েছে।

– একজন পূর্ণকালীন কর্মচারী, কোন নির্দিষ্ট অবস্থান ছিল না এমন ব্যক্তি |

মহামারীর সময়ও অনেক ব্যক্তি কাজ খুঁজছিলেন। অনেকেই আমাদের বলেছিলেন যে চাকরি খুঁজে পাওয়া কতটা চ্যালেঞ্জিং ছিল। তারা একটি শান্ত চাকরির বাজার বর্ণনা করেছেন, যেখানে খুব কম সুযোগ ছিল যা প্রায়শই এমন ক্ষেত্রগুলিতে কেন্দ্রীভূত ছিল যা তাদের পরিস্থিতি, দক্ষতা বা অভিজ্ঞতার সাথে মেলে না: উদাহরণস্বরূপ, কারণ তারা বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করতে পারত না, সীমিত ডিজিটাল দক্ষতা ছিল, অথবা সেই ক্ষেত্রগুলিতে অভিজ্ঞতার অভাব ছিল যেখানে চাকরি বেশি পাওয়া যায়, যেমন স্বাস্থ্যসেবা। যুক্তরাজ্যের মধ্যে ভ্রমণ নিষেধাজ্ঞার অর্থ হল ব্যক্তিরা প্রায়শই কাছাকাছি প্রত্যন্ত অঞ্চলে চাকরি খুঁজছিলেন যেখানে সুযোগ সীমিত ছিল। কিছু ব্যক্তি আমাদের কম বেতনের প্রস্তাব সম্পর্কেও বলেছিলেন কারণ ব্যবসার কাছে অর্থ কম ছিল এবং যাতায়াতের জন্য ভাতা দেওয়া বন্ধ করে দেওয়া হয়েছিল।

| " | আমি যেখানে থাকতাম সেই সময়টা ছিল খুবই গ্রামীণ একটি এলাকা। যাই হোক, সেখানে খুব বেশি কাজ ছিল না এবং ওয়েলসে বিধিনিষেধ অনেক দীর্ঘ এবং অনেক কঠোর হওয়ায় কেউ কোনও কর্মী নিচ্ছিল না।

– স্কটল্যান্ড এবং ওয়েলসের মধ্যে বসবাসকারী শূন্য-ঘন্টা চুক্তি কর্মী ছিলেন এমন ব্যক্তি |

| " | হ্যাঁ, আমি এমন অনেক কিছু খুঁজছিলাম যার জন্য বাইরে যাওয়া বাধ্যতামূলক ছিল না, তাই বাসা থেকে কাজ করা, কিন্তু আমার আসলে কোনও যোগ্যতা ছিল না এবং আইটি অভিজ্ঞতাও ছিল না। বেশিরভাগ চাকরিই এমন ছিল এবং আমি যখন আবেদন করেছিলাম তখনও আমার ভাগ্য ভালো ছিল না।

– স্কটল্যান্ডে শূন্য-ঘন্টা চুক্তিভিত্তিক কর্মী ছিলেন এমন ব্যক্তি |

| " | আচ্ছা, পরে আমি যে চাকরিটি পেলাম, তাতে অবশ্যই বেতন [আমার আগের চাকরির মতো] বেশি ছিল না... আমি যতদূর দেখতে পাচ্ছি, বেতন [কম] কারণ তারা এখন এমন চাকরি দিতে শুরু করেছে যেখানে আপনি বাড়ি থেকে কাজ করতে পারেন, এর বেতনের উপর অবশ্যই প্রভাব পড়বে।

– একজন পূর্ণকালীন কর্মচারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

যারা চাকরি হারিয়েছেন, তাদের প্রায়শই নতুন পদ খুঁজে পেতে লড়াই করার সময় দীর্ঘ সময় ধরে বেকারত্বের সম্মুখীন হতে হয়েছিল। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, জনসাধারণের মুখোমুখি ভূমিকায় কাজ করা একজন ব্যক্তি চাকরি হারিয়ে দেড় বছর ধরে বেকার ছিলেন। ব্যক্তিগত পরিস্থিতির কারণে যাদের কাজের জন্য সীমিত নমনীয়তা ছিল তারা বর্ণনা করেছেন যে কীভাবে এটি কাজ খুঁজে পেতে অতিরিক্ত বাধার সৃষ্টি করেছিল, কারণ নতুন পদগুলি কতটা কম ছিল। উদাহরণস্বরূপ, দুই সন্তানের একজন একক মা লকডাউনের সময় একটি বারে তার কাজ হারিয়েছেন এবং বর্ণনা করেছেন যে তার সময়সূচী এবং শিশু যত্নের চাহিদার সাথে সামঞ্জস্যপূর্ণ আতিথেয়তা চাকরি খুঁজে পাওয়া কতটা অস্বাভাবিক ছিল। তিনি অর্থের জন্য চিন্তিত এবং সুবিধা থেকে তার আয় বাড়ানোর জন্য নমনীয় বেতনভুক্ত বাজার গবেষণার সুযোগ খুঁজে বের করার চেষ্টা করার কথা বলেছেন কারণ তার কোনও সঞ্চয় ছিল না।

| " | অন্য কোন চাকরি নেই, না। এটা একটু কঠিন ছিল, এমনকি রেস্তোরাঁ এবং অন্যান্য জিনিসপত্রও, তুমি জানো... এটা এত কঠিন যে আমার মনে হয় না তখন খুব বেশি লোক নিয়োগ করছিল। অনেক লোক তাদের চাকরি হারিয়েছিল... আমি হয়তো সেই সময়ের মধ্যে আরও বাজার গবেষণার জন্য আবেদন করেছি।

– ইংল্যান্ডে শূন্য-ঘন্টা চুক্তিভিত্তিক কর্মী ছিলেন এমন ব্যক্তি |

আর্থিক প্রভাবের পাশাপাশি, চ্যালেঞ্জিং চাকরির বাজার ব্যক্তিদের সুস্থতা এবং প্রেরণার উপরও নেতিবাচক প্রভাব ফেলেছে। আমরা শুনেছি যে মাসের পর মাস এমনকি বছরের পর বছর ধরে কাজের সন্ধানে অনুপ্রাণিত থাকা কতটা কঠিন ছিল। একজন ব্যক্তিকে একটি দাতব্য প্রতিষ্ঠান থেকে বরখাস্ত করা হয়েছিল যেখানে তারা 25 বছর ধরে কাজ করেছিল। এই আয়ের ক্ষতি এবং দীর্ঘ সময় ধরে কাজ না করার ফলে, তাদের পারিবারিক খরচ মেটাতে তাদের সঙ্গীর আয়ের উপর নির্ভর করতে হয়েছিল, যা তাদের কাছে কঠিন বলে মনে হয়েছিল।

| " | ২০২০ সালের অক্টোবরে আমাকে চাকরি থেকে সরিয়ে দেওয়া হয়েছিল এবং [আমার ভূমিকা] মুখোমুখি। তুমি জানো, [এটা] সম্ভব ছিল না। কিন্তু অন্য চাকরি খুঁজে পেতে আমার ২০২২ সালের জানুয়ারি পর্যন্ত সময় লেগেছিল, তাই অনেক দিন ধরে চাকরি ছিল না কারণ আমার কাজ করা প্রত্যেককেই চাকরি থেকে সরিয়ে দেওয়া হয়েছিল অথবা কেউ কেউ ছুটিতে ছিলেন, তাই কোনও চাকরি ছিল না।

– ইংল্যান্ডে একজন অস্থায়ী/নির্দিষ্ট-মেয়াদী চুক্তিবদ্ধ কর্মী ছিলেন এমন ব্যক্তি |

| " | দ্বিতীয় লকডাউনের সময় আমাকে অকার্যকর করে দেওয়া হয়েছিল, তাই হঠাৎ করেই আমার কোনও আয় ছিল না এবং চাকরির বাজার যখন ব্যাপকভাবে হ্রাস পেয়েছিল তখন আমাকে নতুন চাকরি খুঁজে বের করার চেষ্টা করতে হয়েছিল।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

মহামারী চলাকালীন যারা পূর্ণকালীন শিক্ষা ছেড়ে দিয়েছিলেন তাদের প্রথম চাকরি খোঁজা বিশেষভাবে চ্যালেঞ্জিং বলে মনে হয়েছিল। তাদের সীমিত কাজের অভিজ্ঞতা এবং চাকরির প্রতিযোগিতাকে তারা কঠিন এবং হতাশাজনক বলে বর্ণনা করেছেন। তারা আমাদের সাক্ষাৎকার বা প্রস্তাব না পেয়ে অনেক চাকরির জন্য আবেদন করার অভিজ্ঞতার কথা বলেছেন, যা তাদের কাছে হতাশাজনক বলে মনে হয়েছে।

| " | আমার আরও মনে আছে বিশ্ববিদ্যালয় থেকে বেরোনোর পর চাকরির বাজার কতটা খারাপ লাগছিল, চাকরি পাওয়ার চেষ্টা করা প্রায় অসম্ভব বলে মনে হয়েছিল (যদি এটি ইতিমধ্যেই যথেষ্ট কঠিন না হত!)।

– এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্সের অবদানকারী, ইংল্যান্ড |

তরুণ কর্মীরা বলেছেন যে মহামারী চলাকালীন তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা তাদের ক্যারিয়ারের সম্ভাবনার উপর দীর্ঘমেয়াদী প্রভাব ফেলেছে। তাদের কর্মসংস্থানের ইতিহাসে এখন শূন্যতা রয়েছে এবং তারা বিভিন্ন সুযোগ হাতছাড়া করেছে। কেউ কেউ মহামারী চলাকালীন তাদের দক্ষতা হ্রাসের কথাও বর্ণনা করেছেন; উদাহরণস্বরূপ, একজন তরুণ প্লাস্টার এবং ইটভাটার মিস্ত্রি যিনি কাজ হারিয়েছিলেন এবং অনুভব করেছিলেন যে কাজ না করেই তার দক্ষতা হ্রাস পেয়েছে।