Some of the stories and themes included in this record contain descriptions of bereavement, verbal and physical abuse, mental health impacts, and significant psychological distress. These may be distressing to read. If so, readers are encouraged to seek help from colleagues, friends, family, support groups or healthcare professionals where necessary. A list of supportive services is provided on the UK Covid-19 Inquiry website.

মুখপাত্র

Module 10 is the final of the Inquiry’s modules examining the pandemic’s impact on society. Three records are being produced for the Module 10 investigation: this record covering the experiences of key workers, a record on the impact of the pandemic on mental health and wellbeing and a record on experiences of bereavement during the pandemic.

Every Story Matters closed to new stories in May 2025, so records for Module 10 analysed every story shared with the Inquiry online and at our Every Story Matters listening events up until this date.

The experience of key workers during the pandemic was unique. Whilst for some, the additional recognition of their work and their role was helpful, for many more there were pressures and stresses on them and their families, the likes of which had never been seen before.

The threat of catching Covid-19 and passing it on to loved ones was more pronounced for those who continued to go to their jobs during the pandemic. These were people who put themselves in harm’s way to keep essential services open, to continue educating children and to ensure the rest of the country was able to buy food and other essential items.

Mounting work pressures were compounded by restrictions and co-workers’ absences, confusion and complications from changing guidance brought frustrations, and sadly some key workers reported feeling unsafe in their workplaces because of abuse or guidance not being followed.

Many key workers told us how the pandemic has had a lasting impact on their lives, whether through the debilitating symptoms of Long Covid, mental health impacts, financial effects, impacts on their families, or having to leave their jobs because of burnout.

We sincerely thank everyone who has contributed their experiences, whether online or at events. Your reflections have been invaluable in shaping this record and we are truly grateful for your support.

স্বীকৃতি

The team at Every Story Matters would also like to express its sincere appreciation to all the organisations below for helping us capture and understand the voice and experiences of the key workers that they support. Your help was invaluable to us reaching as many communities as possible. Thank you for arranging opportunities for the Every Story Matters team to hear the experiences of those you work with either in person in your communities, at your conferences, or online.

To the Key Workers, Equalities, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland forums, and Long Covid Advisory groups, we truly value your insights, support and challenge on our work. Your input was instrumental in helping us shape this record.

NAHT: The School Leaders’ Union

NASUWT: The Teachers’ Union

জাতীয় শিক্ষা ইউনিয়ন (এনইইউ)

দক্ষিণ এশীয় স্বাস্থ্য কর্মকাণ্ড

ট্রেডস ইউনিয়ন কংগ্রেস (টিইউসি)

UNISON: The Public Services Union

বিশ্ববিদ্যালয় ও কলেজ ইউনিয়ন (ইউসিইউ)

Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers (USDAW)

ওভারভিউ

This short summary provides a high-level overview of the themes from the many stories we heard about the experiences of key workers during the pandemic.

গল্পগুলি কীভাবে বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছিল

Every story shared with the Inquiry is analysed and will contribute to one or more themed documents called records. These records are submitted from Every Story Matters to the Inquiry as evidence. This means the Inquiry’s findings and lessons to be learned will be informed by the experiences of some of those most affected by the pandemic.

In this record, contributors describe their experience as key workers during the pandemic. They include those working in the police service, firefighters, education staff, cleaners, transport workers, taxi and delivery drivers, security guards, public facing sales and retail workers and funerals, burials and cremation workers. The experiences of key workers in healthcare and social care have been included in the records for Modules 3 and 6 respectively, so are not duplicated here. The Inquiry team and researchers have:

- Analysed 55,362 stories shared online with the Inquiry, using a mix of natural language processing and researchers reviewing and cataloguing what people have described.

- ইংল্যান্ড, স্কটল্যান্ড, ওয়েলস এবং উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ডের শহর ও শহরের জনসাধারণ এবং সম্প্রদায়ের গোষ্ঠীগুলির সাথে "এভরি স্টোরি ম্যাটার্স লিসেনিং ইভেন্টস" এর থিমগুলিকে একত্রিত করা হয়েছে।

For other Every Story Matters records, targeted research has often been carried out to capture specific experiences. For this record, the themes focus on stories shared with the Inquiry by key workers online and through events. This reflects the scope of Module 10 and the range of evidence about the experiences of key workers that will be gathered by the Inquiry in other ways during its investigation.

More details about how key workers’ stories were brought together and analysed in this record are included in the Introduction and in the Appendix. The document reflects different experiences without trying to reconcile them, as we recognise that everyone’s experience is unique.

Throughout the record, we have referred to people who share their stories with Every Story Matters based on their job role or sector. When attributing quotes to these people, we have tried to keep these as consistent and specific as possible to their role based on the information they provided.

Some stories are explored in more depth through quotes and case illustrations. These have been selected to highlight specific experiences and the impact they had on key workers. The quotes and case illustrations help ground the record in peoples’ own words. Contributions are anonymised.

Please note that this Every Story Matters record is not clinical research – whilst we are mirroring language used by participants, including words such as ‘anxiety’, ‘OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder)1’, ‘PTSD (Post-traumatic stress disorder)2’, this is not necessarily reflective of a clinical diagnosis.

Impact of the pandemic on key workers

Fear and uncertainty at the start of the pandemic

The beginning of the pandemic was characterised by overwhelming fear and uncertainty for key workers. Many reflected on how afraid they were about contracting Covid-19 at work and potentially becoming seriously ill. They felt very uncertain about what Covid-19 and the restrictions would mean for their work and what the impact might be on them.

The immediate impact on key workers was dramatic, with working practices changing overnight and minimal time to establish new ways of working. Many key workers were frustrated about a lack of planning for a pandemic in their sectors.

Interpreting and implementing pandemic restrictions

One of the most significant challenges for key workers was interpreting and implementing government guidance in specific workplace contexts. The guidance often felt ambiguous, leaving those managing services to make difficult decisions about applying broad principles to their specific circumstances.

This included head teachers and school leaders who were frustrated about the constantly changing guidance, often announced to the public via the media before schools were told. We heard how council officers had to interpret confusing and sometimes contradictory messaging for local residents while dealing with changing guidance. The frequent changes created additional stress for key workers dealing directly with the public, leaving workers uncertain about what advice to give or rules to enforce.

Frontline key workers faced practical problems implementing restrictions due to the nature of their jobs. Social distancing was impossible for nursery workers providing care for young children, prison officers who needed to restrain prisoners and police officers visiting Covid-positive households for extended periods. Some key workers felt the requirements of their roles were incompatible with the safety measures being emphasised to the general public.

Impact on workplace safety

A lack of appropriate Personal protective equipment (PPE) left many frontline key workers feeling unsafe and undervalued. Retail workers told us they worked for weeks without any protective equipment while mixing with customers. Key workers told us that when they received PPE, it was often insufficient, inadequate, or both. Police officers described using masks later proven ineffective against Covid-19, while council workers, charity workers and cleaners faced significant problems accessing the PPE they needed.

The physical environment of workplaces presented additional challenges. Buildings with smaller rooms and windows that did not open made proper ventilation impossible in some workplaces. School staff noted how maintaining social distancing in classrooms and corridors with large numbers of students was impossible. Similar problems existed in airports, prisons and police stations which were sometimes crowded, poorly ventilated spaces.

Key workers in education settings described how the implementation of ‘bubbles3‘ in education was particularly challenging. School staff found themselves mixing with children from many households and feeling highly exposed to the virus, especially when schools remained open for some during lockdowns.

Impact on workload and ways of working

The pandemic brought unprecedented workload pressures that often continued for many months. Funeral directors described working extended hours with no respite, dealing with the increase in deaths because of Covid-19 while trying to support grieving families. Teachers reported teaching in person all day and then setting online work in their own time.

Workload pressures worsened when colleagues were furloughed or self-isolating. Staff shortages often became chronic due to repeated isolation requirements, which remaining staff often had to cover. Exhaustion from these working conditions led many to leave their jobs, citing burnout.

Some key workers also experienced increased verbal and physical abuse from the public. In some cases, retail workers described receiving abuse when enforcing restrictions and funeral workers felt blamed when explaining and implementing government guidance about funerals and mourning practices. This added emotional stress to keyworkers in an already challenging situation.

Impact on personal and family life

The fear of spreading Covid-19 to loved ones was very real for key workers, particularly those who were clinically vulnerable themselves or had vulnerable family members. Many workers who had to go into their workplaces took steps to try and protect family members, including removing or washing work clothes when they got home. For some, these actions became habitual and continue today, with some developing anxiety or OCD-like symptoms.

Fear of spreading Covid-19 led to painful decisions about isolation for key workers. Some stopped seeing elderly parents or sent children to stay with relatives. This contributed to feelings of loneliness, with workers also missing significant life milestones.

Managing childcare created enormous challenges for frontline key workers. Parents described juggling shift work with reduced childcare options and the strain this put on relationships between partners.

Long Covid has had profound impacts on affected key workers. Doctors often did not understand the condition, creating frightening and isolating experiences. Many also described dealing with debilitating symptoms, with some forced to take extended time off work and careers significantly impacted when employers would not accommodate necessary adjustments.

Key workers who contracted Long Covid sometimes saw their income reduced and accumulated debts they are still repaying. In these cases, they often did not receive sick pay when self-isolating, which had a significant financial impact.

Mental health impacts

Key workers described long-lasting and detrimental impacts on their mental health. Many described feeling burnt out because of a combination of fear, increased workload, lack of support and family pressures. Some said they developed anxiety, depression and PTSD. The lack of employer support was also a consistent theme, with management reported often to be more focused on maintaining services than worker wellbeing.

For some, continuing to work during the pandemic provided purpose and routine, helping to alleviate the anxiety and stress that came with additional workload and personal pressures.

Recognition and pride

Many key workers did not feel appreciated for the personal sacrifices they made and the risks they took during the pandemic. They wanted better recognition and more practical support for key workers. This included funerals, burials and cremation workers who were frustrated that they did not have key worker access to priority shopping and Covid-19 vaccines.

Those in frontline roles during the pandemic thought it was important to clarify what jobs should be recognised as key worker roles. Many working outside the health and social care sectors felt strongly about this, especially when this status shaped how the public saw their work.

However, some thought the pandemic had brought greater recognition of their sector and the important work they did, including some key workers in transport, food and retail. This contributed to a sense of pride in their contribution to the pandemic response.

শেখা শিক্ষা

Key workers reflected on lessons for future pandemics. They emphasised the need for clear, unambiguous guidance relevant for their work, with established processes for checking implementation. They thought consistency across sectors and proper oversight of safety standards were essential.

They believe advance planning should extend to all essential sectors, with comprehensive plans for implementing safety measures. Key workers emphasised that the pandemic demonstrated how much society relies on retail workers, cleaners, transport workers as well as other essential workers.

They felt it was important to have a clear national policy which defines key worker status and ensures equal recognition and consistent eligibility for support. It was repeated many times that this support should include sick pay for all key workers, proactive mental health support, and priority access to PPE and vaccines for all frontline workers.

-

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental health condition where a person has obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd/overview/

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition caused by very stressful, frightening or distressing events. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/overview/

- Bubbles involved keeping groups of children together in consistent, isolated groups throughout the day, with minimal interaction between different bubbles. This was intended to limit the number of potential contacts and help facilitate faster and more efficient contact tracing by NHS Test and Trace when a positive case was identified within an education or childcare setting.

1 Introduction

This document presents stories from key workers about the impact of the pandemic on their work and what that meant for them and their families.

Backgrounds and aims

Every Story Matters was an opportunity for people across the UK to share their experience of the pandemic with the UK Covid-19 Inquiry. Every story shared has been analysed and the insights derived have been turned into themed documents for relevant modules. These records are submitted to the Inquiry as evidence. In doing so, the Inquiry’s findings and lessons to be learned will be informed by the experiences of some of those impacted by the pandemic.

This record brings together what key workers told us about their experience of working throughout the pandemic and the impact it had on them, their workplace and their families. This includes those working in the police service, firefighters, education staff, cleaners, transport workers, taxi and delivery drivers, funeral workers, security guards and public facing sales and retail workers.

The UK Covid-19 Inquiry is considering different aspects of the pandemic and how it impacted people. For Module 10, there are three Every Story Matters records detailing the specific impacts on society, covering key workers, mental health and wellbeing and bereavement. This record outlines the impact on key workers.

Some topics have been covered in other Module 10 records or in the records from previous modules. For example, the impact on healthcare key workers is explored in the Every Story Matters record for Module 3 and the impact on adult social care workers is included in the record for Module 6. Therefore, not all key worker experiences shared with Every Story Matters are included in this document. You can learn more about Every Story Matters and read previous records at the website.4

লোকেরা কীভাবে তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা ভাগ করে নিয়েছে

There are two different ways Every Story Matters has collected the experiences of Key Workers for Module 10:

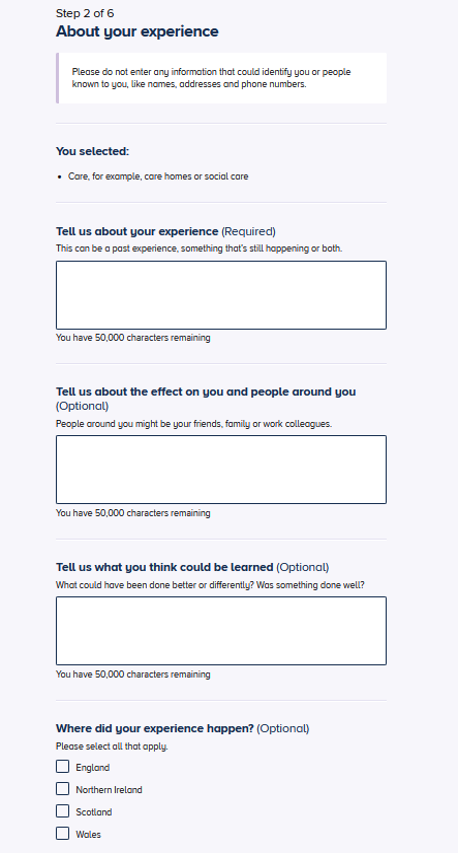

- Members of the public were invited to complete an online form via the Inquiry’s website (paper forms were also offered to contributors and included in the analysis). More contributors were women and from England. The form asked people, who identified themselves as key workers, to answer three broad, open-ended questions about their pandemic experience. It also asked other questions to collect background information about them (such as their age, gender and ethnicity). This allowed us to hear from a very large number of people about their pandemic experiences. The responses to the online form were submitted anonymously. For Module 10, we analysed 55,362 stories. This included 45,947 stories from England, 4,438 from Scotland, 4,384 from Wales and 2,142 from Northern Ireland. Contributors were able to select more than one UK nation in the online form, so the total will be higher than the number of responses received. Also, the far greater number of responses from England has meant that many of the quotes used were from people living in England. The responses were analysed through ‘natural language processing’ (NLP), which helps organise the data in a meaningful way. Through algorithmic analysis, the information gathered is organised into ‘topics’ based on terms or phrases. These topics were then reviewed by researchers to explore the stories further (see Appendix for further details). These topics and stories have been used in the preparation of this record.

- Every Story Matters Listening Events. The Every Story Matters team went to 43 towns and cities across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to give people the opportunity to share their pandemic experience in person in their local communities. Virtual listening sessions were also held online, if that approach was preferred. We worked with many charities and grassroots community groups to speak to those impacted by the pandemic in specific ways. Short summary reports for each event were written, shared with event participants and used to inform this document.

গল্পের উপস্থাপনা এবং ব্যাখ্যা

It is important to note that the stories collected through Every Story Matters are not representative of all experiences of key workers and the impact of the pandemic. We are likely to hear from people who have a particular experience to share with the Inquiry. The pandemic affected everyone in the UK in different ways and, while general themes and viewpoints emerge from the stories, we recognise the importance of everyone’s unique experience of what happened. This record aims to reflect the different experiences shared with us, without attempting to reconcile the differing accounts.

আমরা যে ধরণের গল্প শুনেছি তার প্রতিফলন ঘটানোর চেষ্টা করেছি, যার অর্থ হতে পারে এখানে উপস্থাপিত কিছু গল্প যুক্তরাজ্যের অন্যান্য, এমনকি অনেক লোকের অভিজ্ঞতার চেয়ে আলাদা। যেখানে সম্ভব আমরা উদ্ধৃতি ব্যবহার করেছি যাতে লোকেরা তাদের নিজস্ব ভাষায় কী ভাগ করে নিয়েছে তার রেকর্ড তৈরি করতে সহায়তা করে।

Some stories are explored in more depth through case illustrations within the main chapters. These have been selected to highlight the different types of experiences and the impact these had on people. Contributions highlighted in case illustrations have been anonymised and described based on the main themes in the contributor’s experience.

Throughout the record, we refer to people who shared their stories with Every Story Matters as ‘key workers’, ‘workers’ or ‘contributors’. Where appropriate, we have also described more about them (for example, the sector they worked in or their job title) to help explain the context and relevance of their experience. We have also included the nation in the UK the contributor is from (where it is known). This is not intended to provide a representative view of what happened in each country, but to show the diverse experiences across the UK of the Covid-19 pandemic. Stories have been collected from November 2022 to May 2025, meaning that experiences are being remembered sometime after they happened.

Some key workers are identified by specific roles (such as ‘Deputy head teacher’ or ‘Traffic officer’) while others are described more generally (such as ‘Teacher’ or ‘Key worker’). This reflects the information contributors chose to provide when sharing their stories with the Inquiry. We have used job roles or sector details where available and relevant, respecting that contributors shared only what they were comfortable disclosing.

In some instances, we have also made the role descriptions consistent: for example, where quotes describe general workplace experiences relevant to any staff in education settings, we have used ‘Education worker’ rather than specific roles like ‘Teacher’ or ‘Teaching assistant’.

রেকর্ডের কাঠামো

This document is structured to allow readers to understand how key workers were affected by the pandemic. The record is arranged thematically with a range of key worker experiences across different sectors captured across all chapters:

- Chapter 2: Impact on work and workplace safety

- Chapter 3: Impact on personal and family life

- Chapter 4: Lessons learnt

2 Impact on work and workplace safety

This chapter describes the impacts on work and workplace safety for key workers during the pandemic. It covers how workplaces interpreted pandemic restrictions and implemented measures to protect safety of staff. It also outlines how key workers experienced these changes to their roles and ways of working.

Fear and uncertainty at the start of the pandemic

Some key workers reflected on how frightened they were at the start of the pandemic about contracting Covid-19 at work and becoming seriously ill. They felt very uncertain about what Covid-19 and the restrictions put in place would mean for their work and what the impact might be on them.

| " | At the start of the pandemic, it was very scary – something out there that could harm us but was unable to be seen and not sure how it was caught.”

– Key services worker, England |

| " | I watched in my classroom with all the other teachers. We were all afraid. The news was we’d shut but there were exceptions.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

Key workers reflected on the immediate impact on their work. Some said their experiences early in the pandemic suggested there was a lack of planning for responding to the crisis in their sectors, adding to the fear and uncertainty for key workers.

| " | There was a clear lack of planning and proper preparation by the health service, forces and government to respond to what was a reasonable assumption that such a pandemic would occur.”

– Police officer, England |

| " | It was obvious we were not prepared nationally, at a local level or as a fire service to readily broaden our role to assist.”

– Fire and rescue service volunteer, England |

Interpreting changing government guidance

Many key workers thought a lack of clarity in government guidance made their working lives more challenging during the pandemic. They described how much had to be done to interpret guidance for roles and ways of working in their organisations. This added to the stress and pressure for those responsible for managing services and settings, who were also finding ways to adapt and continue operating.

| " | Guidance from government needed to be more precise and defined rather than ambiguous.”

– Education worker, England |

| " | Doing funerals was the hardest thing I did, explaining the rules and how I was going to interpret and enforce them. How our building would be prepared. Holding the anger of people was really difficult emotionally … ”

– Priest, England |

A repeated concern among key workers was the confusion caused by guidance changing as the pandemic went on. In some cases, council officers had to keep updating their communications and advice to local organisations who were unclear what the guidance meant for them in practice.

| " | I … was a key worker and member of the Local Resilience Forum (LRF) – finding myself at the forefront of trying to interpret and share confusing and sometime[s] contradictory government messaging for local residents, responding to queries, supporting the setting up of vaccination centres, keep essential services running, as well as keeping local councillors and officers informed and safe. Although we weren’t working on hospital wards, and didn’t deserve or expect the recognition of our NHS colleagues, it was, nevertheless, relentless and exhausting.”

– Council officer, England |

| " | At the time of the first lockdown I was working for a local authority in the education department … The DfE [Department for Education] were issuing new guidance weekly and then daily. We were attending Teams meetings every day to work out how to interpret it and get advice to schools and families. It was coming out so fast you would go in each day not knowing what was next.”

– Council officer, England |

Head teachers and school leaders were frustrated about government guidance for schools and education settings. They said the guidance was initially unclear and then kept changing, often at very short notice. Finding out about changes at the same time as the public was incredibly stressful, leaving schools without the time they needed to put updated measures in place. This added to workload pressures for school leaders and staff.

| " | The day after school closure I woke to a message from an angry parent demanding to know what arrangement I had made for keyworker children. Schools were not informed before this was announced in the media. This was a repeating pattern. Every change was announced on the news before schools were told. The other pattern was significant changes being announced on the first day of school holidays meaning I had to work instead of a break.”

– Head teacher, England |

| " | I was left to do my own research and listen to what the government were discussing. I then had to use my own analysis to reach very important decisions that my staff, children and their families were relying on … This meant that in my role, I was taking important decisions about who would come into school and who would not.”

– Head teacher, England |

| " | One of the most difficult things was reacting to government guidance which often came out late, required a huge amount of input to implement in a short period of time e.g. the advice about bubbles for the return to the face-to-face school in September 2020 turned up in August.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | Latest updates would be broadcast on the TV daily to the nation and as an education provider we would receive the update at the same time as the nation. We were expected to put things in place immediately causing stress and causing extra workload.”

– Assistant head teacher |

The frequent changes to guidance were also difficult for other key workers, especially those dealing with the public. Retail workers shared feelings of frustration and said they felt unsupported while at work.

| " | When I worked in [supermarket] no-one seemed to know what the guidance was at any time … that comes down to the government not giving set rules and they were always changing.”

– Retail worker, England |

Implementing pandemic restrictions

Many frontline key workers faced practical problems following guidelines and implementing pandemic restrictions because of the nature of their jobs or their working environment. We heard how stressful this was and how key workers constantly felt at risk from Covid-19 and often became ill with the virus. The personal impact on key workers is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

Mixing closely with others

Some key workers had to have direct physical contact with people to do their jobs during the pandemic. This often involved mixing with people for whom they cared or supported. We heard examples from nursery workers of how they had to be close to the young children they were looking after.

| " | Working in a nursery I was required to work throughout Covid. This was very worrying considering it is impossible to provide proper care for young children without being in close contact.”

– Nursery worker, Scotland |

Education staff described how their students did not understand that they needed to socially distance from staff and other pupils as much as possible.

| " | Students do not know boundaries and crowd round each other and staff. You can ask them to move back and separate but they ignore you or do it for a few minutes, forget and then crowd round each other again.”

– Secondary school teacher, England |

| " | Teaching was awful – trying to keep children 2m apart, constantly washing their hands until they were red raw.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

Prison officers and police officers needed to work closely with people to do their jobs too, meaning that social distancing was not possible. They worried about their exposure to the virus at work as a result and felt uncared for and undervalued.

| " | I work in the prison service so continued to work as I was a key worker … we felt like we were cannon fodder as no one seemed to care about our welfare, no social distancing in work, we were scared of what could happen while trying to do our jobs.”

– Prison officer, England |

| " | I worked as a response police officer throughout the pandemic. I was visiting households who were Covid positive multiple times per day. On some occasions these interactions with Covid-19 patients were for prolonged periods in excess of 8 hours in a confined space, involved physical confrontation or exposure to bodily fluids.”

– Police officer, England |

A prison officer who felt at risk from Covid-19 at workA prison officer shared her experiences of working in prison during the pandemic. Her husband was also a prison officer. She reflected on the stress and uncertainty there was around pandemic restrictions and workplace safety in prisons. After returning to work, she and her husband wanted to take steps to protect themselves from Covid but faced barriers in the prison where they worked. “We were told that we could not wear masks as we would be suspended if we did as they didn’t feel there was a need. When they got masks for the prisoners we were told we had to wear masks or we would be suspended. We had to unlock [cells] and offer exercise and showers and phone calls to prisoners with Covid further risking ourselves and our families.” Social distancing was not possible for prison officers because of cramped buildings and needing to restrain prisoners. She also said there was a lack of concern about spreading the virus and said many prisoners did not follow Covid-19 measures. This made her feel that there was little she and her husband could do to reduce their risk of infection. “We were told to stay so far away from people (not possible on a landing which is only so long on the 2nd, 3rd and 4th floors and we’re having to restrain fighting prisoners with Covid). They were still transferring prisoners into [Category C] jails even though there was a full lockdown going on and we had to deal with them. We were spat at by prisoners with Covid and worked [an] extra 9 hours per week to keep the jails safe.” “We caught Covid at work numerous times and was so unwell that my husband was hallucinating and we stuck to the rules [at home] at all times.” |

In shops, staff could not always socially distance from customers because of the way some customers behaved. Some retail workers had to deal with people who were less concerned about the risks of Covid-19, making the workers feel unsafe and thereby increasing their risk of infection.

| " | Working in a supermarket during Covid was a unique time. People were forced to queue 2 metres apart outside but as soon as they got inside they all acted like everything was normal and would walk straight up into you without a second thought. Often coughing right behind you. No one followed the rules and if I complained because it wasn’t safe, I was the problem.”

– Retail worker, England |

| " | I worked in a large supermarket and … I found that customers were split into two camps, those that were petrified and those who thought it was just a version of flu. These people didn’t always wear masks, they would literally push us out of the way to get what they wanted (toilet rolls etc) and our managers just stood back because they didn’t know what to do.”

– Retail worker, England |

| " | I was appalled at the lack of concern the general public had. They treated coming to the pet shop like a day out. They would come in wearing no or ill-fitting masks and berate us for having to limit the number of people allowed in the shop at the time.”

– Retail worker, England |

Other key workers had to work closely with colleagues even if they had limited direct contact with the public or people using services. This sometimes included mixing with large numbers of people for long periods or different people each day. This left them feeling anxious and frustrated that they had no choice but to work in this way.

| " | When it came to working on the railway it was a total shambles … we had different vans but when we got to site men were working in close proximity, as welders we were always working within 2 foot of each other. As I said total shambles.”

– Transport worker, England |

| " | As an essential or key worker in an environment with over 100 other colleagues, I felt a level of anxiety which I managed to dispel by looking after other colleagues who felt in a similar state.”

– Food sector worker, England |

Some roles like police officers and firefighters involved travelling in pairs or groups of colleagues in vehicles during the pandemic. This meant they could not socially distance from one another. In some cases, who they mixed with would also change, meaning key workers were in practice mixing with a wider group of colleagues.

| " | I was a front-line emergency services worker (firefighter) during the pandemic. I felt that little was done to protect us. Staff were regularly in close contact with staff from other areas as a way to cover shortfalls in staffing and external contractors were brought on to our premises in large numbers throughout lockdown. Yes shortfalls needed to be covered, but arrangements were given little thought. Meaning that staff from a 70 by 30-mile geographical area regularly intermingled.”

– Firefighter |

| " | As a Traffic Officer for National Highways, I was classed as a ‘key worker’ and was required to attend work throughout the lockdown periods … Traffic officers were still being paired up with a colleague to work in a vehicle together and the pairings changed each day. Thankfully, this changed after about a week as our internal guidance caught up and we then started to work in vehicles on our own and generally distance ourselves from each other at work.”

– Traffic officer, England |

| " | I’d spent a long 10-hour shift in the cab within the shedding window of a colleague who went on to test positive for covid 19. During the shift we had both removed our P2 masks for drink and substance breaks which was standard practice. It was an extremely busy time and the shifts were non-stop from start to finish, from job to job, with our thirty-minute meal break often being 8 or more hours after starting.”

– Firefighter seconded to ambulance, England |

পিপিই

Key workers relied on PPE to reduce the risks from Covid-19, particularly when social distancing was difficult or impossible. Many key workers in frontline roles said they did not have access to appropriate PPE at the start of the pandemic. We heard examples of some essential retail workers who described how they continued to work as normal without protective equipment, despite mixing with customers and colleagues when at work. They were often angry that they were put at risk and felt undervalued.

| " | I worked in retail branch banking pre and post pandemic. We had to stay open every day, classed as an essential worker. We had no PPE for almost two months. No one recognised us for being open and helping the community.”

– Retail branch banker, England |

| " | For weeks on end there was no protective equipment, gloves, masks, screens, etc, and I was still expected to do my job as if nothing had changed, and when we did get PPE there was never enough to last more than a day or two.”

– Retail worker, England |

| " | I and my colleagues were told by our employer that disposable PPE had to [be] wiped & reused which resulted in several of us contracting Covid.”

– Security worker, England |

A retail worker who faced limited Covid-19 protections at workWe heard from a retail worker who was in her early 60s when the pandemic started. She said there was limited support around workplace safety in the early stages and worried about how this put her at risk from the virus due to her age. “It seemed to me that everyone was being frightened into staying home and covering up and yet the only people who could not do this at all and who were exposed to literally hundreds if not thousands of new people every day without proper PPE were supermarket workers.” She thought her managers protected themselves but did not introduce proper Covid-19 safety measures for staff on the shop floor working directly with customers. “We had no barriers, masks or hand sanitisers available to us for a long time. It was observed that managers could and would isolate themselves as much as possible whilst floor workers could not. There was also a difference between what was being publicised and what was really going on i.e. the 2-metre rule was impossible to implement behind the shop floor.” She blamed mixing with others at work for catching Covid-19. After having the virus, she was told she had to return to work quickly or she would not be paid. “Because my cough could upset customers I was asked to do work off the shop floor and in fact was tasked with some very physical outside work which made me very ill within a few days again. From then on, I was at work and off work continually.” She could not understand why she was not better protected at work, particularly when comparing her experiences to other key workers. “When finally they put up screens at the tills, which personally I felt were a waste of time, no risk assessments were carried out for till workers then having to work the tills in an abnormal stance and overreaching causing significant strain on the shoulders in particular. It caused pain when constantly pulling and pushing heavy items from the conveyor belt to enable people to access their goods further away.” |

Some police officers said they did not have the PPE they needed. This left them feeling like they had no alternative but to take personal risks while working directly with other people. We also heard how police officers tried to reduce their exposure to the virus by resorting to other measures, such as alternative face coverings or working outside.

| " | We struggled to access effective PPE early on. We used a variety of masks that were later never used again as [they were] proven to be less effective”

– Police officer, England |

| " | There was a considerable lack of PPE within Policing, social distancing did not exist and large groups of on duty officers were forced to work with no protective equipment, no alternative work accommodation and to work in close proximities with both colleagues, those in need of Policing and their families/friends.”

– Police officer, England |

| " | We attended incidents involving the public that occurred on our road network. We did so without face masks. We were told that the organisation couldn’t get hold of any face masks because they had all been diverted to the NHS. Thankfully, most of our work is done outside so we had fresh air and distancing on our side. It was quite a long time later that we were supplied with face masks.”

– Traffic officer, England |

Other key workers said they were not prioritised for PPE, even as the pandemic continued and more supplies were generally available. This included charity and council workers and cleaners. They were deeply frustrated and angry that they had been left without adequate protection and some described facing significant barriers to accessing the PPE they needed.

| " | I worked through the whole of Covid for a local council. I worked in a frontline service – Community Alarm. Quite frankly we were used as lambs to the slaughter and the staff did [their] best to keep everything running while the management hid away and basically glory chased. As long as they could say they provided a service while they were safe at home they were happy. We had to fight to get the full PPE we needed. We had to fight to get hand sanitizer.”

– Council worker, England |

| " | I help run a small outreach charity … feeding the homeless, vulnerable and those on the edge of society on a Friday evening … Access to PPE was ridiculously limited, it’s horrifying that we took such risks (necessarily) without proper protection.”

– Homelessness worker, England |

| " | We did not know where our PPE was coming from, not quite seen as frontline workers; we were often left to get on with things and given leftover PPE that wasn’t deemed fit for NHS services.”

– Homelessness worker, England |

We also heard from education staff about feeling anxious because they were told that they should not wear face masks in the classroom, even though that contradicted general government messaging about staying safe during lockdown.

| " | I felt very anxious hearing Boris’ broadcasts about how it was unsafe to leave your house yet I was expected to go to school and teach children all day with no face mask etc as this could impair their ability to understand me and may frighten them.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

Work environments

The design of buildings also influenced how well key workers could implement Covid-19 measures and how safe they felt. Many schools, prisons, shops and transport hubs did not have space to allow for social distancing. Key workers told us about how crowded or confined spaces meant they had to work with a high risk of contracting Covid-19.

| " | The concept that schools were safe environments in which to work was totally ludicrous. For instance, the idea that teachers standing behind a taped line at the front of a classroom containing 30 students was deemed to be safe, then followed by hundreds of people moving through crowded corridors and staircases. The government repeatedly stated that schools were safe environments due to the measures implemented, my case and many others proved that this was not the case.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | [Problems with immigration at airports] caused large crowds in a confined space with poor air conditioning also it caused excessive delays in passengers getting through immigration. Meaning the crowds would be together longer and the staff had to remain in the area with them trying to enforce social distancing and mask wearing rules which at times became very challenging.”

– Airport customer service officer, England |

Another practical concern for key workers was how difficult it was to follow guidance about ventilating buildings.

| " | Putting the rules into practice in a school that was built in 1896 was a challenge. Being told to have good classroom ventilation is no use if you have tiny Victorian windows that barely open. Impractical rules that cannot be followed was stressful on staff and children alike.”

– Teaching assistant, England |

| " | It was never mentioned on television … police officers catching Covid and spreading it among colleagues and probably the public due to a mostly windowless building.”

– Police officer, England |

Key workers in education discussed how air filtration systems were available to tackle problems with ventilation, but said these were not installed everywhere they were needed. Some key workers did not have access to any ventilation systems and had to deal with situations where people reduced ventilation by closing windows.

| " | We needed ventilation in the form of fresh air with high air changes per hour and air filtration units installed for hard to ventilate spaces or where thermal comfort would need to be maintained during the winter months. WE GOT NEITHER OF THIS INVESTMENT. Our current school ventilation guidance of 1500ppm CO2 does ABSOLUTELY NOTHING to reduce the risk of Covid infection … ”

– Education worker, Northern Ireland |

| " | Passengers on buses were most unhelpful in closing windows open for ventilation despite drivers’ requests.”

– Bus driver, England |

A few key workers said it was easier to implement pandemic restrictions in their workplaces. A worker in manufacturing shared how it was straightforward to isolate different teams in the factory where they worked.

| " | I had to continue working as I work in a factory producing food, so we stayed open. We had to wear masks at all times and were isolated into sections … i.e. prep team, mix and weigh team etc were not allowed to interact.”

– Factory worker, England |

Organising and maintaining ‘bubbles’ in education and childcare

Many key workers in education and childcare told us about practical problems with ‘bubbles’during the pandemic. Trying to implement bubbles led to confusion in education settings and increased fear about catching and spreading the virus. For example, education staff were in bubbles with their classes or sometimes larger groups. This meant that they worked closely and mixed with students from many households. Working on the frontline was frightening and many key workers, including those in education, felt disposable, as if their health had to be compromised to fulfil their role.

| " | Come September 2020, we had yet another set of guidance, rules and ways of teaching as children all returned to school but in separate bubbles. During the 2nd lockdown (November 2020), I felt like a lamb to the slaughter as schools remained open and children could form support and childcare bubbles … ”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

One nursery worker described how trying to maintain bubbles put strain on staff and children’s relationships in the nursery and how they were unclear on what to do when children had symptoms.

| " | When lockdowns ended and we operated in “bubbles” it was incredibly difficult. It affected social relationships of children and staff alike. The procedures for isolating a child displaying symptoms and confusion over who constituted contacts and should isolate led to anxiety and panic attacks.”

– Nursery worker, Scotland |

A teacher’s experience of ‘bubbles’ in a primary schoolOne primary school teacher shared how frightened she was about catching Covid-19 from being in a bubble with her class. She was angry about being exposed to risk from the virus, particularly when looking after the children of other frontline workers. “Our school had a ‘bubble’ in every class (15 children), such was the demand and need from our families. Due to the nature of the key workers eligible to send their children to school, teachers were put at high risk of contracting Covid from the children. For me, this was terrifying.” “Teachers were not given priority for the vaccine (unlike other countries) and we literally lived in fear every day. Several staff contracted Covid from the children and became seriously ill and were hospitalised. The impact of this on our mental health was huge.” Hearing about parents catching the virus made her and her colleagues worry for their own families even more. “We had parents who tragically passed away during this time, which hit everybody incredibly hard. The rest of us lived in daily fear of Covid and taking it home to our families.” Working in this environment was not easy and she felt the media portrayal of teachers was unfair and had a negative impact on her mental health. “On top of this stress, the media portrayed teachers as lazy. The reality was far from that. This led to huge amounts of stress. I did not sleep. I developed OCD [Obsessive–compulsive disorder] around cleaning and hand washing and lived in absolute fear of contracting Covid. I would cry every day before having to go to work and spend my day in a high state of anxiety.” |

Impact on roles and ways of working

Increased workloads and staff shortages

Some frontline key workers experienced increased workload pressures early in the pandemic because demand for services rose. This increased workload often continued for many months and often left them physically and mentally exhausted.

| " | Because of my job role, I went to work every day during the pandemic and was even made to take a full-time job because of the increase in people buying online. I was worked to the bone, physically and mentally struggling with my workload AND taking fertility medication.”

– Postal worker, England |

| " | I was incredibly stressed and put my exhaustion down to burn out. My class ‘bubble’ had burst on numerous occasions that term and I’d been testing relentlessly as a result.”

– Teacher, Northern Ireland |

A funeral director’s experiences of workload pressuresA funeral director told us about the significant increase in the scale and complexity of her workload during the pandemic and the intense pressure she experienced as a result. “The pressure was relentless. With the surge in deaths, my colleagues and I found ourselves working 70+ hour weeks, often without a break. There was no respite, no downtime, just an endless stream of services to organise, people to prepare, and families to console.” As with other frontline key workers, she feared bringing Covid home to her family. “We followed all the protective measures, but the risk was always there, hanging over every interaction and task. At times this risk was a total unknown, we didn’t know if Covid was transmissible from deceased to us. This fear wasn’t just mine – every funeral director I knew shared it. We lived with the dread of infection, the isolation periods, staffing challenges and balancing our professional duties and our compassion with the desperate need to protect our loved ones.” The workplace pressures were greatly exacerbated by how difficult it was emotionally to support grieving families during the pandemic. “The hours were gruelling, but it wasn’t just the physical exhaustion that wore us down—it was the emotional toll of constantly being surrounded by some of the most complex grief and loss we had ever experienced, this was loss on a different scale.” However, she and her colleagues did not give up and were proud of being there for the people who relied on funeral services. “Yet, through all this, we kept going. We showed up every day, often without the support or recognition we deserved, because it was our duty to help families in their darkest hours. We provided compassion, dignity, and care when it was needed most. Working as a funeral director during the pandemic was a trial by fire, but it also reaffirmed the importance of our work and our commitment to serving others, even when no one was looking.” |

We also heard how workload pressures were worsened when colleagues were furloughed or moved to other roles. This was especially frustrating when there was too much work for key workers who continued in their roles.

| " | All the agency workers and the [EU] drivers left and went back home leaving the company undermanned my company was one of the big warehouse used by the government to supply and deliver the PPE to hospitals so we were busy which meant I was away from home from Sunday night to Saturday late morning and having to live, wash, eat in my truck being sent all over the UK.”

– HGV (heavy goods vehicle) driver, England |

As time went on, key workers faced further workload pressures because of staff shortages linked to the pandemic.

| " | I tried to make sure all the drivers had masks and hand sanitizers. Some drivers lost their jobs for refusing [to wear masks] whilst others resigned over the issue. This left us with a massive shortage of staff, particularly as there were other absences due to shielding etc., with one driver ending up doing the work of four, which was stressful.”

– Transport sector manager, England |

One of the most common reasons for this was staff having to self-isolate because they had contact with someone who had Covid-19 or had caught the virus themselves.

| " | Staff were off isolating over and over again and we were expected to cover for them and were run off our feet constantly. It was exhausting, many of my colleagues quit teaching as a result of burn out from the increased workload Covid absence had.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

Needing to shield or leaving their roles because of concerns about pandemic measures led to feelings of guilt for some of those unable to be on the frontline.

| " | This [youngest child being clinically vulnerable and shielding] also prevented me from returning to work when schools started to reopen further causing a lot of resentment amongst other staff.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | Firstly, as a person who was identified as vulnerable (asthma), I had to stay away from work from 23rd March 2020. I am a teacher. It was so alien to teach from home, especially as most of my colleagues were not vulnerable and were on a rota to go in and teach vulnerable children or those children of key workers – I suffered terrible guilt in the first lockdown which led to increased anxiety.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | I felt guilty that I got paid while I stayed at home because I was on the vulnerable list, while my colleagues had to go to work.”

– Retail worker |

A few key workers said they were helped by staff from outside their team or even their organisation. This alleviated some pressure on these key workers, as was the case in retail.

| " | Due to people being off because of Covid we were short staffed which put a lot of pressure on the workers, business, and management. Our local sports centre volunteered to come and help us with home delivery and click and collect orders. 15-20 people who would have normally worked in the sports centre came and helped us every week for around two months.”

– Retail worker, Scotland |

Some young retail workers felt pressured by employers to work additional hours, even when living with vulnerable relatives. They said this increased their exposure to the virus and added to the stress they felt at work. These younger workers said employers asked them to work more because they were less likely to be severely affected by Covid-19 and therefore should continue working throughout the pandemic.

| " | My supervisor would always ring up asking me to cover shifts so I ended up working way more than normal while the pandemic was on, and so many of my mates were doing nothing at home trying to stay away from the virus, but there I was being asked to go in loads because I was young and they kept saying you’re not affected by Covid you can go in.”

– Retail worker |

| " | The management [was] so rude during Covid, I get they were stressed but like when I said I couldn’t work because I live with my mum they were just saying young people are not affected by this, there was so much pressure particularly on [us] younger people working at the store.”

– Retail worker |

Verbal and physical abuse

Some frontline key workers experienced a rise in verbal and physical abuse from those who were frustrated by the pandemic restrictions or did not agree that they should be in place. This led to an incredibly stressful work environment, with staff left to enforce rules they saw as confusing.

| " | Also the amount of abuse we received daily due to the restrictions from customers was a massive impact to all colleagues.”

– Retail worker, England |

| " | While in work we would be subject to abuse daily, I’ve been spat on for refusing entry without a mask, I’ve been called racist for enforcing the same rules I enforced on everyone else and I would have people every day tell me that it’s not real, it’s a joke.”

– Supermarket retail assistant, Wales |

| " | Every day myself and my colleagues felt we were coming into contact with far too many people, and whilst a lot of people were respectful in keeping a distance and grateful we were open, there were some that would be verbally abusive towards us if we were trying to restrict numbers at the door, some that would not wear masks, and that made us fearful for our health and that of our families when there was little information being given to us.”

– Retail worker, Northern Ireland |

Retail workers from ethnic minority backgrounds said they sometimes faced racialised verbal abuse when trying to implement government guidance. This abuse came from both the public and, in some instances, their colleagues.

| " | Every day, minorities had issues and abuse due to Covid.”

– Retail worker |

| " | I was racially abused and the person who racially abused me [at work] was dismissed.”

– Retail worker |

Young retail workers also experienced workplace abuse, which they said was often directed at younger women

| " | Customer behaviour has really got[ten] worse in Covid and kind of stayed like that, and those who bear the brunt of that are our young workers, people think they can say what they like to younger people particularly young women, which is why it’s so important that they get their voices heard.”

– Retail worker |

Abuse was also a problem for funeral workers supporting bereaved families. We heard from a funeral worker who felt blamed when explaining and implementing government rules about funerals and mourning practices.

| " | I regularly received abuse, daily, due to government rules, and the fact that families blame us for those rules, and the fact that they could not grieve their relatives as they wished.”

– Funeral worker, England |

Adapting to new ways of teaching

Many teachers described having to adapt in different ways because some children were taught remotely and others attended school in person. Learning how to use new technology while also teaching in person with Covid restrictions meant the pressure continued as the pandemic went on.

| " | I have never worked so hard in my entire life trying to support staff and learners remotely. When people were able to return to work a lot of members of staff had childcare responsibilities so could not work. I think education and nursing staff were outstanding and I honestly do not think people respect how much personal sacrifices they made to ensure the safety of others.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

| " | The second lockdown … I spent all day at work teaching the ones in school then setting all the online work and communicating with the home school group after work in my own time. I didn’t have any energy left to home school my own 2 children.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

A music teacher’s experience of adapting ways of workingA music teacher shared how challenging it was to move to online teaching at the start of the pandemic. “When the first lockdown happened, I had to learn how to use all the Teams software over the Easter holiday.” When her students later returned to schools in person, she had to adapt in different ways, dealing with following the guidelines and introducing cleaning protocols to reduce the risk of spreading the virus. “Following the first lockdown when the whole school was back, it was very stressful as following the regulations meant my working day was chaotic. The lessons overlapped by 15 minutes making the timetable complicated. I had to take all my equipment to each classroom (11 in all over the course of 3 days a week), making sure to clean every instrument down after every use.” She saw some staff take the rules more seriously than others as she moved between classrooms. This was worrying given she was older and more vulnerable to the virus. “There was some friction between staff as some were more concerned than others about following the rules. Some classrooms I went into had all the windows and doors shut so had no ventilation at all. I was already in my 60s and govt [government] information was that those over 60 were more vulnerable so I wanted to be extra careful.” She had to adapt teaching methods to accommodate social distancing and hygiene as well as ensuring pupils continued to enjoy their lessons. “I was responsible for … making sure all Covid-safe regulations were being followed. As time went on, I would take classes outside to sing and I would wear a visor. In fact, we got so used to singing outside that we recorded our carol service on the hill outside the music room. This meant I spent 5 hours a day teaching outdoors through November and December.” |

Funerals, burials and cremations

Key workers responsible for funerals, burials and cremations were frustrated about not being able to support grieving families as they usually would during the pandemic. They emphasised how worried they were about the mental health impact of the restrictions on bereaved people but also on their own mental health. Many felt distraught being unable to provide their usual services and how this affected the grieving process.

| " | The whole funeral process became an emotionless disposal service and has left a massive mental health crisis in waiting.”

– Funerals, burials and cremation worker, England |

| " | The funerals we took during that time were appalling. I have never been so ashamed as I was of those funerals. I have always given funerals my all but I was prevented from doing this during lockdown. … staff presiding, lockdown funerals were heartless examples of officialdom that has lost its way. They were soul-less and loveless as we shouted words of comfort at grieving family members (only 10 allowed this week, no 20 this week, no none at all this week, pick a number) from a distance of 20 yards, in the rain, outside because we weren’t allowed in the building. Even a 12 year old boy could not have a hug from his dad as he said goodbye to his Mum.”

– Funerals, burials and cremation worker, England |

| " | Devastating for all of us as funeral professionals, knowing we weren’t able to provide the service we normally would, or that we would want to.”

– Funerals, burials and cremation worker, England |

Overall reflections on workplace safety

Some key workers reflected on how their sector or organisation approached workplace safety overall, often because they were involved in discussions as union representatives or had raised concerns with their employers. We heard examples of key workers who felt undervalued by their employer’s approach to workplace safety. These contributors were often frustrated about the lack of consistent health and safety guidance during the pandemic, with some feeling that workplaces had carried out inadequate risk assessments for their work environment. This made key workers feel their concerns about health and safety were dismissed, and that they were being put at risk so organisations could continue to operate.

| " | Frustration. For example when we knew that bus drivers in London were being affected in large numbers, we should have had the common sense to advise our bus drivers in [Greater Manchester] to wear protective masks … we were unable to implement such interventions because there was ‘no evidence’ or it was not in the ‘PHE [Public Health England] Guidelines’ … very frustrating.”

– Bus company worker, England |

| " | I work in the North Sea and the companies were given the green light to continue on as normal, international and national travel for the workforce even during lockdowns, the installation I work on did not want to change anything which meant putting people into close contact with others from different households … the suggestions I made to protect people were ignored and I was stopped from working from a malicious manager using mental health against me, I had contacted the HSE [Health and Safety Executive] who enforced the exact things I suggested so they had to do the right thing in the end.”

– Utilities/communications/financial worker, England and Scotland |

| " | Colleagues were literally terrified from the outset … We felt ‘disposable’, made to continue to bring in the revenue, despite the unknown risks. Families of colleagues were anxious and worried about loved ones out there and when you came home, what was you bringing in? Arguments and questions put enormous strain on families and relationships. The risk assessments implemented by the company were not adequate or reflected the work we did. Many felt let down, failed and used.”

– Key services worker, England |

| " | During Covid we were expected to continue as normal. Safety measures were late to be implemented and inappropriate, governmental guidelines regarding masks and social distancing were not followed. As [a] department we were put at risk and our concerns belittled and dismissed by all levels of management.”

– Council worker, England |

An electrician’s experience of workplace safetyA university electrician shared his experience of workplace safety during the pandemic. He thought the approach taken by his employer did not properly assess the risks staff faced. “I am an electrician and union Health and Safety rep and was classed as a critical worker (proud of that) but was disturbed to receive a risk assessment from my employer that viewed Covid-19 (March 2020) as a low risk and had no staff or unions involved in the process.” He said there were no safety measures put in place at the start of the pandemic. He thought managers working from home did not care about implementing Covid-19 protections. “23rd March 2020, I arrived at the campus and discovered that no plans had been implemented to keep staff safe and we were managing ourselves while management were at home giving the illusion of caring for us. As a critical worker, I was expecting only important jobs to be undertaken (how wrong I was) [but the] vast majority of tasks were noncritical which was highlighted to senior management but just ignored.” The way workplace safety was managed made him feel like he and his colleagues were not a priority compared to the university being ready to reopen. “There seemed to be a mini industry in manufacturing tasks just to keep bodies at work. I believe management wanted the campus ready for returning students!” |

3 Impact on personal and family life

This chapter describes the impacts of working during the pandemic on key workers’ personal and family lives. It covers their worries about catching and spreading Covid-19, the pressures on relationships and financial concerns. It also discusses the impact on key workers’ mental and emotional wellbeing.

Fears about catching and spreading Covid-19

We heard from many key workers who were deeply fearful about catching Covid-19 at work. The risk of catching Covid-19 at work was a daily and significant cause of stress and anxiety, particularly early in the pandemic when less was known about the virus. Key workers were afraid about what catching Covid-19 would mean for them, their loved ones and other people they were mixing with.

| " | I was expected to go to work, in retail, mixing with the general public whilst not being able to see my own children. This had a huge mental effect, causing anxiety and depression.”

– Food retail worker, Wales |

| " | I worked as a TA [teaching assistant] and was on the frontline taking care of key worker and vulnerable children. It was terrifying as we didn’t know what we were dealing with.”

– Teaching assistant, England |

| " | We all felt at my place of work very anxious, because we all still had to carry on working when the rest of the country were on lockdown. My family were constantly telling me, ‘Don’t bring that virus home’.”

– Food delivery driver, Wales/England |

Fears about spreading Covid-19 to those they lived with were sometimes overwhelming, particularly for key workers who were clinically vulnerable, or living with clinically vulnerable people. They described the unfamiliar things they did to manage the risks of spreading the virus, including removing their clothes when they got home, or washing work clothes immediately. For some, these actions, initially adopted out of precaution, became habitual and continue to shape what they do today. In some cases, contributors said they have since been diagnosed with mental health conditions like anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

| " | My parents are elderly and have health conditions. I was constantly worried about passing Covid on to them.”

– Education worker |

| " | I was a teaching assistant to a whole class as well as my role 1-2-1 to a particular child with special needs. The child constantly licked the palms of his hands, holding hands with other children and myself … It was incredibly stressful, exhausting and extremely worrying as my husband is immunocompromised.”

– Teaching assistant, England |

| " | I continue to be very concerned about hygiene. I still haven’t caught Covid and remain concerned about eventually catching it. I am still wary about using public transport and wear vinyl gloves whilst doing so … my concerns around touch points and hygiene are similar to OCD and are ongoing. There have been some minor disagreements with my wife about how I act in terms of cleaning and hygiene as she feels I’m going too far.”

– Food industry worker, England |

A cleaner afraid of spreading Covid-19 to her clinically vulnerable familyWe heard from a cleaner who was living with her husband, her daughter who was pregnant and her son with Mosaic Down’s Syndrome during the pandemic. She worried about the risks of bringing Covid home to her family and said there was not enough protection at work to support her safety. Her concerns focused on personal protective equipment (PPE) not being used properly or managed safely by her colleagues. “Staff at my workplace used the same PPE every day without changing it even though they were getting into customer cars. In the office they left used PPE and used positive tests on desks and didn’t wear PPE when walking about.” Her fears were realised when her family caught Covid-19. She was reluctant to seek medical help because she was afraid of visiting hospital. Her son was also clinically vulnerable which added to her fears of her family members dying if they caught the virus. “I caught Covid and took it home to my daughter, son and partner … We all became very ill very quickly and because of the news on TV I refused to be admitted to hospital, the news reporting that hospital admission [equals] certain death” As she and her husband recovered, their son’s condition worsened. Her son was then rushed to hospital after collapsing and she was not allowed to go with him. He died from Covid-19 in hospital shortly after. “My son died without any family member being with him. I will always carry the blame for causing his death as I took Covid into our home.” After her son died, she struggled with continued poor health and worried about the limited safety measures at her workplace. Raising these concerns with her employer did not improve the situation, so she flagged the workplace safety issues with the local council instead. This led to tensions with her employer and she had to resign from her job. “I reported incidents to my employer and to the workplace both before and after my son’s death with neither party taking any actions. Eventually I contacted health and safety through the local council who took matters very seriously and dealt with every one of my concerns and complaints which were upheld and which of course led to my resignation as the workplace and my employer wanted to sack me.” |

Others shared how fear of passing Covid-19 on to others led them to distance themselves from vulnerable friends or family members. This contributed to feelings of loneliness and isolation. Some key workers reflected on the sense of loss they felt at having missed out on significant milestones and life events because they were afraid of spreading the virus.

| " | We did not see my mum and sister and my husband’s parents for 2 years. They are vulnerable people, particularly my mum, and because I work in secondary education and was in/out of work covering key workers’ care it was very difficult and I found this upsetting.”

– Education worker, England |

| " | I am in close contact with [people who had died from Covid-19]. My children had to stay with my dad 100 miles away as I felt it was the only way to keep them safe from me possibly carrying Covid home.”

– Funerals, burials and cremation worker, Wales |

দীর্ঘ কোভিড

Many key workers told us how they caught Covid-19 during the pandemic. Some shared how frightening and debilitating it was when their symptoms continued and they developed Long Covid. We heard about the life changing impacts of the disease.

| " | I dealt with Long Covid symptoms I was left with, early on in Covid’s existence. Doctors did not understand what I had and could not explain it. It was a frightening, isolating time. All I knew was that Covid attacked any underlying health issues I had, and it was life changing.”

– Education worker |

| " | Contracting the Delta variant left me in a state of severe illness [Long Covid], with debilitating symptoms for months. Though my oxygen levels stabilized at the critical moment, sparing me from hospitalization, I was still left to fend for myself with no clear guidance or support.”

– Education worker, England |

| " | I was miserable and exhausted from suffering with Long Covid. My partner ended up doing everything for me.”

– Utilities/communications/financial worker, England |

| " | Long Covid is still killing people in the Black community. Some people are dying slowly, especially in the Black community.”

– Retail worker |

Key workers who developed Long Covid said there should have been more understanding and consideration of the condition from employers, even though little was known about it early in the pandemic. They felt more focus on Long Covid would have helped support key workers living with the condition, including managing their return to work where that was possible.

| " | That there should be more understanding of this type of Long Covid.”

– Key services worker |

| " | I and other members of the team I work with are suffering with symptoms of Long Covid. We have lost staff at a dramatic rate due to the lack of concern or respect by anyone in authority of the childcare sector.”

– Childcare worker, England |

| " | As a result of my experiences with Long Covid, I was forced to take a year off work in my job as a secondary English teacher. I then returned on a part time basis. Three years in, I have only just been able to return full time.”

– শিক্ষক, ইংল্যান্ড |

Living with Long Covid affected some key workers’ ability to work and earn money. One education worker told us about the impact on her career.

An education worker’s experience of support with Long CovidAn education worker reflected on how she received limited support with Long Covid from both her workplace and the health system. She told us how she carried on working when she first experienced symptoms, but months later she had to leave her job because they would not accommodate the adjustments she needed. “I have had Long Covid for over 2 [years] now. I left my job 7 months after trying to push through it. My boss initially was forthcoming and supported me well, but before I quit they would not accommodate me and my Long Covid anymore.” She still lives with Long Covid and says returning will not be an option without proper support. She also worries how she will survive financially as she believes that Long Covid can be a difficult condition to prove or evidence which would allow her to receive financial support. “I then got into a Long Covid clinic. Initial assessment was good and I was given breathing techniques and pacing help but that was it. I was expecting more but not sure what! … Support from my GP has [been] and is minimal … Relapses are hard even now and the prospect of returning to work seem hopeless … Financial help is hard too as Long Covid is not deemed a disability or named condition.” |

Recognition and pride

Key workers across different sectors shared how they did not feel appreciated for the personal sacrifices they made and the risks they took during the pandemic. They were often frustrated that they did not receive the same level of public recognition as healthcare workers, including being excluded from public displays of support such as the “Clap for Carers”. Many were angry that they were not valued as they should have been.