Executive Summary

This report does not represent the views of the Inquiry. The information reflects a summary of the experiences that were shared with us by attendees at our Roundtables in 2025. The range of experiences shared with us has helped us to develop themes that we explore below. You can find a list of the organisations who attended the roundtable in the annex of this report.

In May 2025, the UK Covid-19 Inquiry conducted a roundtable focused on the impact of the pandemic on cultural institutions. A group discussion was held with representatives from arts and cultural sector organisations, charitable foundations and trade unions. Sector-specific terminology is used in this report – a glossary has been provided at the end of the document to explain any terms that may be unfamiliar.

The first lockdown meant cultural venues closed and arts activities, such as arts programs, workshops, classes, performances and community engagement, stopped immediately. Performing arts were particularly affected given the reliance on activities happening in person. Organisations in the sector reacted quickly to try to understand and implement government guidance and support cultural organisations, individual practitioners and freelancers.

Organisations found that early pandemic guidance was not clear, making it difficult to interpret rules and implement them in practice. Confusion about the guidance continued as the pandemic went on, particularly as restrictions eased and organisations planned for and implemented different approaches to reopening after pandemic restrictions eased. Representatives said this added to the stress on organisations and individuals working in the sector.

Individuals and organisations who were working to move creative practices and services online needed support as many had been used to running activities in person and had limited digital experience. Larger cultural organisations set up platforms to offer help. Some cultural organisations also adapted their services to meet community needs, such as providing food delivery services or art materials to schools.

The screen sector, which includes film, television, video games and other video-based media, thrived because of increased demand for entertainment content during lockdowns. Many of those who had previously worked in the performing arts moved to the screen sector to find work, and some have not switched back because of ongoing demand.

Recognising the complex relationship between individual workers, cultural organisations and commissioners was described as important to understanding how they work together to create content and the impact of the pandemic. This includes challenges in communication and coordination, particularly with freelance workers. Having a large freelance population made it challenging to communicate important information during the pandemic, particularly where workers were not part of a union or representative body bringing them together. This problem was further compounded by freelancers finding it difficult to access financial support during the pandemic compared to cultural organisations.

Many cultural organisations had structured processes in place that allowed them to apply for and receive financial support in the pandemic, often through the Cultural Recovery Fund.1 This financial support enabled organisations to continue operating. In the devolved nations, the Cultural Recovery Fund was seen as more straightforward to access for individual workers than in England due to eligibility constraints.

Despite the financial support in place, representatives agreed that overall the pandemic had reduced financial resources in the sector, with many organisations depleting cash reserves to survive. Newer venues also struggled to meet changing eligibility requirements for financial support later in the pandemic because they could not demonstrate they had been operating for long enough. In some cases, these financial pressures meant organisations taking on debt or having to close.

There was strong consensus that the financial support available did not recognise that many freelancers and sole traders work or are paid flexibly. The nature of freelancers’ working history and variable incomes meant they often had difficulty demonstrating they qualified for financial support, with many not meeting eligibility requirements.

Representatives said that the eligibility criteria and changes to the Cultural Recovery Fund throughout the pandemic had lasting impacts on freelancers and individual practitioners. Many individual workers were left without access to financial support and this led to them seeking jobs outside the sector.

Representatives reflected on how the mental health and wellbeing of those working in the sector became more of a priority for cultural organisations during the pandemic. They said the pandemic also highlighted and exacerbated long-standing inequalities experienced by some workers in parts of the sector, including family policies for working parents that were felt to be unfair, barriers facing working class people and wider issues of representation of some groups.

The numbers of volunteers was said to have declined during the pandemic. Many volunteers were reluctant to return to their roles because of concerns about contracting Covid-19. As many small and medium sized cultural organisations are reliant on volunteering roles, this left some without the workforce they needed to support them in reopening.

During the pandemic, organisations developed new ways to reach out to different audiences, rather than relying on regular consumers of arts and culture who would normally come to cultural venues in person. Representatives described how they felt communities became more aware of the role and value of the cultural sector as a result.

The pandemic was also seen to have changed the behaviour of those attending cultural activities. Clinically Vulnerable groups at higher risk from Covid-19 were noted as feeling less confident returning to live performances and events. Representatives also highlighted that phased re-openings were confusing for audiences, making it more difficult to persuade people to attend. They described a consistent pattern of last-minute ticket bookings since the pandemic, and said that less social interaction meant that audiences sometimes acted inappropriately upon returning to venues.

When considering lessons for future pandemics, representatives highlighted the need for better data collection to improve understanding of the sector and strengthen preparedness. Representatives wanted pandemic decisions to be informed by sector expertise, so that policies and guidance better support resilience and reduce the negative impact on the sector. They also stressed the importance of flexible financial support mechanisms that recognise the unique complexities of the sector, particularly the important role played by freelancers.

- This was a fund set up to tackle the financial crisis that faced cultural organisations and heritage sites during the pandemic. This involved providing funds to the culture sector to help maintain jobs and keep businesses afloat. https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/culture-recovery-board

کلیدی تھیمز

Impact of restrictions on cultural institutions

The first lockdown required cultural venues to close and pandemic restrictions meant organisations and individual practitioners in the sector could no longer provide cultural services. This meant arts programming, workshops, classes, performances and community engagement stopped.

| " | It had an obvious immediate impact because all arts venues, theatres, had to close…there’s a huge loss in things like workshops, classes, participatory work, community engagement…people had long term programming that was abruptly shut down.”

– Arts Council Northern Ireland |

Creative Scotland described how the performing arts sector was particularly affected given how heavily reliant performing arts shows and activities are on in-person interaction and direct contact with audiences and communities.

Representatives discussed the importance of sector organisations reacting quickly, to understand and implement government guidance and support local organisations, individual practitioners and freelancers early in the pandemic. For example, Arts Council England described how their organisation created a £160 million Covid-19 Emergency Response Fund within three weeks of the first lockdown.2 This allowed them to provide financial assistance to organisations and individuals in the sector, including those from ethnic minority communities.

| " | [We] had an emergency response fund…that meant we could cashflow organisations, we put money into individuals and we also funded organisations that were outside of our portfolio…we were also able to make sure that organisations from under-represented communities were supported. £13.1 million went to BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) individuals and organisations, and d/Deaf or disabled individuals or organisations. That was something that was really important for us.”

– Arts Council England |

Cultural organisations described the guidance as unclear, both initially and as the pandemic progressed, making it difficult for them to interpret the rules and implement them in practice. Confusion about the guidelines also meant some organisations sought advice from sector organisations and trade unions, while others were left to interpret available information independently, adding to the pressure they felt. This confusion continued as the pandemic went on, restrictions eased, and organisations planned for and implemented different approaches to reopening.

The venue type and performance timings also affected how the rules should have been applied. The Music Venue Trust gave an example of a lack of clarity about whether the imposed 10pm curfew for serving drinks applied to grassroots venues.3 They said venue operators felt there had not been enough support in place to help them understand and implement the guidance and that the details had not been communicated clearly. As a result, after venues began reopening, the Music Venue Trust faced significant licensing issues because they believe the guidance was incorrectly interpreted by licensing enforcement officers. This was stressful for venue operators who had to liaise with enforcement officers about applying the rules correctly. It also created confusion for customers. The Music Venue Trust said they used learning from their discussions with venues to develop their own guidance around approaches to reopening.

Impact on ways of working

How the sector adapted

Representatives highlighted how the pandemic accelerated the shift to performances and cultural activities being produced and accessed online across the sector. They emphasised how important this was to maintaining public engagement in arts and culture during the pandemic.

Individuals and organisations who were trying to move creative practices and services online needed support. Many had been used to operating and collaborating in person and had limited digital experience. Representatives discussed how some larger cultural organisations stepped in to provide help, for example by offering online hubs for creative collaboration or for operational support. Video-conferencing tools enabled online discussions and creative expression despite restrictions.

| " | What was important for us in our response was to try to support people to stabilise but also to support people to find avenues and opportunities for their creative practice to develop and engage with audiences. That moved from live to digital…there was something about our ability [as a national body] to put online resources together, but also to bring people together on online platforms.”

– Creative Scotland |

The Music Venue Trust described how live-streaming performances began during the pandemic as an important way of supporting continued engagement in arts and culture. However, they said since the pandemic there has been a reduction in live-streaming as it was not a replacement for in-person events.

| " | There were periods [when] people did pivot into digital [ways of working], but that was not an ongoing replacement for the live experience. There are very, very few gigs that are live streamed nowadays.”

– Music Venue Trust |

In the screen sector, representatives said there was an increase in demand for high quality content for television and streaming services because people were spending more time at home, including furloughed workers. This demand allowed those in the screen sector to continue working as more content was being produced. Many of those previously working in the performing arts moved to the screen sector to find work and some have not switched back because demand has continued.

| " | The screen sector also was thriving. It was partly because there was a way of mobilising the sector with government guidance to get thriving…many of them [performing arts staff] moved to the screen industry and some of them haven’t come back.” – Creative Scotland |

Bectu (Broadcasting, Entertainment, Communications and Theatre Union) explained that despite the rising demand for content, production shutdowns and restrictions still prevented many in the screen sector from working. They described how some of these workers had to find jobs outside their profession to survive financially, meaning they lost specific skills they had developed and needed. Overall, this led to a loss of skills in the sector.

| " | We had lots of people working in supermarkets or doing whatever they could during that period of time just to keep themselves going. Undoubtedly, it has impacted upon the skills within the sector.”

– Bectu |

Staff working for venue operators were said to have gained skills in applying for financial support. The Music Venue Trust explained how training was provided for staff which included drop-in sessions to discuss various avenues of additional funding available. This allowed more employees to complete funding applications and manage the process correctly during the pandemic.

مواصلات

Communication with cultural organisations about key issues like guidance and funding was generally straightforward because of established links across the sector. However, representatives discussed how having a large freelance workforce made it challenging to share important information about the pandemic response with everyone who needed it.

Trade unions or representative bodies sometimes acted as a central hub for sharing communications with individual workers, as they were able to communicate with all their members. However, those who were not union members or part of a representative body did not always receive information that would have helped them. The Arts Council England gave an example of how difficult it was to inform individual workers that they were pausing National Lottery project grants. This meant that those in receipt of this support were not informed in a timely way that they would lose this income.

| " | You had people who were quite divorced from what was happening in the information flow. We took the decision to pause Lottery grants…that was their income. I remember we weren’t getting that message across.”

– Arts Council England |

Creative Scotland said they were able to disseminate information through their website, helping inform those working in the sector by supporting them with interpretation of guidance.

| " | We were turning that around quite quickly and putting it through our website into the public domain. It was able to enable people working in the sector to inform their own activities.”

– Creative Scotland |

Workforce impact

The pandemic led to exceptional levels of stress and uncertainty across the sector. Representatives agreed that the mental health and wellbeing of the workforce became an increased priority for cultural organisations.

The pandemic also highlighted and exacerbated long-standing inequalities in the cultural sector, including barriers for working parents and the underrepresentation of some groups of people within the sector e.g. those who are from ethnic minority or working class backgrounds.

| " | [Members] wanted us to achieve better pay and stability for them…they wanted us to deliver dignity at work…and the third thing that people wanted to challenge in terms of this culture of resilience was in terms of their mental health as well. One thing we’ve invested heavily in is mental health services.”

– Equity |

The combination of an uncertain environment and exacerbation of preexisting inequalities meant leaders were forced to navigate complex and difficult issues, often without prior experience or training. This led to some leaders and workers experiencing mental and physical health problems and burnout.

| " | The issues of burnouts, leaders leaving the industry…with everything shut down and creative attempts to keep different types of work going, it really exposed the complex web of inequalities and pressures of our sector.”

– Paul Hamlyn Foundation |

Bectu highlighted how venues reopening placed additional pressure on their members because they risked contracting Covid-19 in enclosed work environments. They said staff were fearful about being exposed to the virus, while facing exhaustion from working longer hours to cover Covid-related staff shortages in their organisation.

| " | The reopening was challenging in theatres for several reasons, not least restrictions around how many people could attend, but also because of crew illness. That was really challenging for our members because there were still people suffering with Covid. Long hours and shortage of staff challenges were difficult.”

– Bectu |

Equity (a performing arts and entertainment union) explained how building resilience became more important for their members as the pandemic continued. Their members emphasised the importance of ensuring income stability, dignity at work and proper mental health support.

Arts Council Northern Ireland also shared how the numbers of volunteers in the arts sector declined during the pandemic. Many were reluctant to return due to concerns about contracting Covid-19, particularly older volunteers or those living with clinically vulnerable people. Small and medium organisations had previously been reliant on volunteers and this often left them without the workforce they needed when reopening.

| " | In terms of reopening, [cultural institutions were] impacted by the loss of experienced staff who had moved to other sectors, but also volunteering [staff]. We found a lot of organisations were reporting an impact from that.”

– Arts Council Northern Ireland |

Impact of financial support

Representatives discussed the impact of the Cultural Recovery Fund, predominantly given to organisations and heritage sites, as well as support for individual workers offered via Universal Credit.

Many cultural organisations had structured mechanisms and processes in place for funding, enabling them to apply for and receive financial support during the pandemic. Initially, funding was usually received through the government’s Cultural Recovery Fund. Representatives discussed how valuable this financial support was for cultural institutions and venues, enabling them to continue operating. However, they thought that even with this support, the sector has suffered financially overall because organisations also used their cash reserves to survive.

| " | The pandemic depleted everyone’s resources. When we did start to come back through, people didn’t have the financial reserves or the reserves of goodwill because [they] were exhausted. It [financial reserves and goodwill] creates the conditions for potentially quite generative conversation about where we go next.”

– Paul Hamlyn Foundation |

The Music Venue Trust also found that 67% of funding they were involved in distributing was spent on rental costs because of the high levels of private ownership of music venues. They said managing this funding put unnecessary pressure on organisations like theirs when support could instead have been provided directly to landlords.

As the pandemic progressed and rules about funding changed, organisations were sometimes no longer eligible for financial support. The Music Venue Trust said that grassroots venues which had opened just before the pandemic did not meet the updated eligibility requirements as they could not demonstrate that they had been operating for long enough. This resulted in these organisations taking on more debt to stay afloat. In some cases, this also resulted in closures.

There was a strong consensus that the financial support available to individuals working in the sector did not recognise that many freelancers and sole traders are contracted and paid on a flexible basis. Furthermore, sole traders often could not meet Universal Credit eligibility requirements because they did not meet regular working hours or income. This added to the stress experienced by many working in the performing arts and entertainment sector. This was a particular concern in the film and television industry according to Bectu, despite the increased demand for screen content. The overall rise in demand did not provide sufficient work opportunities for some freelancers who still needed financial support.

| " | I think for us, as an organisation that only funds other organisations, we don’t fund individuals, we were keenly aware there was a huge amount of concern in the organisations we fund about freelancers. We did do two proactive pieces of work around freelancers, which is something we don’t normally do.”

– Esmée Fairbairn Foundation |

Some workers had been on maternity leave or were early in their careers and could not provide evidence of past income. Some people in the screen sector also worked via limited companies which could not access support.

| " | What we found was there was then much more of a problem in adjusting some of the schemes that had been put in place to make sure they covered people. Freelancers were the biggest issue here.”

– Musicians’ Union |

This left many freelancers and workers without their usual income or other financial support, meaning they often had to find other work to supplement their income or leave the sector altogether. Large numbers of freelancers leaving the cultural sector during the pandemic was something representatives said they deeply regretted. They explained how essential freelancers are to keep the sector running.

| " | There were so many people in our sector that because you had to be employed on one date and then another date, they just didn’t qualify for [the Cultural Recovery Fund]…just because of the variety of the ways people are engaged.”

– Bectu |

Representatives said that eligibility criteria and changes to the Cultural Recovery Fund as the pandemic went on had lasting impacts on freelancers and individual practitioners. Bectu stated that these changes also reduced the amount of funds that organisations could apply for meaning they needed to make spending cuts to continue operating.

Access to financial support through the Cultural Recovery Fund was thought to be more straightforward in devolved nations. Representatives described this as having a positive impact on retaining the sector workforce in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

| " | We found the Cultural Recovery Fund, the way it was allocated in the devolved nations, we know of quite a lot of members in Wales and Scotland who were given grants. Individuals found it much easier to access some of that money. We saw very little of that in England.”

– Musicians’ Union |

Impact of restrictions on communities

Impact on public engagement with culture

Representatives noted how much local communities missed cultural activities and thought the value of culture was increasingly recognised as the pandemic went on. They also discussed how the pandemic led to local cultural organisations becoming more closely linked with their communities. This included using innovative ways of reaching people who did not usually engage with arts and culture before the pandemic.

| " | Lots of cultural organisations, their learning and engagement teams [were] out there working with communities in ways they’d never done before. Different kinds of civic interaction. Huge amounts that were incredibly innovative.”

– Paul Hamlyn Foundation |

Larger organisations shifted their focus from a national level to a more community-based approach. This led to a stronger presence for arts and culture within the communities across the UK. Arts Council England described how these efforts to reach out to local communities strengthened the local value of cultural organisations, their work and services.

| " | A strength, many of our organisations connected with their local communities in a way they’d never done before. We saw quite big organisations seeing themselves as very much community-based in their local places. We saw that at all levels. People who live locally saw a value for them.”

– Arts Council England |

Representatives also described how some organisations adapted their work to meet other needs in the local community. Paul Hamlyn Foundation highlighted inequalities they had been working to address before the pandemic and that remain a priority now.

| " | [Some] organisations were able to say, ‘We’re a food delivery service now because that’s the important thing in our communities. We’re going to schools and providing art materials to kids who don’t have access to culture’.”

– Paul Hamlyn Foundation |

Impact on audience behaviour

The pandemic was seen to have changed the behaviour of those attending performances and cultural activities. Arts Council England reported on the concerns of clinically vulnerable groups at higher risk from Covid-19. These groups felt less confident about returning to live performances and events, whether as audience members or performers. Their hesitation stemmed from doubts that safety guidelines would be adequately enforced. Creative Scotland said for likely similar reasons that older audiences had been slower to return to arts and culture venues compared to younger ones.

| " | Vulnerable groups throughout this have had some really challenging times. People who were having to self-isolate for audience members and practitioners…were far less confident to come back.”

– Arts Council England |

Representatives highlighted the fact that audiences found phased re-openings and different restrictions in different parts of the UK confusing. It left audiences feeling uncertain about whether they were allowed to attend performances, when, in what region and nation. For example, Creative Scotland considered it likely that slower re-openings in Scotland influenced the slower rate of audience return.

| " | It wasn’t really a one nation strategy and there were differences in the reopening and closing strategies, which meant audiences were very much out of sync…there was that public interaction of relief of getting back into these spaces and because of differences in guidance and lack of clarity, confusion which then did permeate through the rest of the Covid phased openings.”

– Music Venue Trust |

Representatives also noted a consistent pattern of last minute, or later, bookings for events. Arts Council England explained that for performing arts this was likely affected by caution among older audiences about attending live events.

| " | The habits have changed. Late ticket buying [since the pandemic], but the other thing we’re also seeing is spending overall is down by audiences. I think it’s been reinforced by a post-Brexit world, the environment and overall challenges that are being experienced by people in their domestic lives.” – Bectu |

Bectu said they observed an increase in abuse towards staff at arts and culture venues, particularly those working in front-of-house roles. They believed long periods of lockdown with less social interaction meant that audiences sometimes acted inappropriately on returning to venues. This resulted in staff experiencing behaviour which was not previously common at live events and impacted on how safe they felt at work.

| " | Audience behaviours, what our members tended to find was that people had maybe forgotten how to behave when they go to the theatre or events. We saw quite a huge uptick in abuse of staff, front-of-house and just generally…singing and interrupting and shouting.”

– Bectu |

-

- A fund comprising reserves and repurposed funding streams to create a £160m Emergency Response Package. This package supported organisations in and outside Arts Council England’s National Portfolio, as well as individual artists and freelancers. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/covid19/emergency-response-funds.

- These are places where musicians and music professionals develop their skills and hone their craft, test out new ideas and approaches, and prepare to engage with and develop audiences. https://www.musicvenuetrust.com/resources/grassroots-music-venue-gmvs-definition/

Lessons for future pandemics

Representatives suggested key lessons that can be learned from the experience of the arts and culture sector to better prepare for and respond to future pandemics.

- Better data collection to improve understanding and preparedness: Representatives described a need for more robust evidence to improve understanding of the sector and its audiences and the likely impact a future pandemic might have on arts and culture. They felt that this would improve preparedness and enable information to be available immediately, allowing the sector to respond promptly and efficiently.

- Involve the sector in pandemic decision making: To prepare and respond to a future pandemic, representatives wanted sector-specific expertise to be better integrated in decision making and strategy. They wanted organisations in the arts and culture sector to be approached proactively rather than reactively, so that future decisions about pandemics support resilience in the cultural sector and reduce negative impacts. They also felt that this type of approach would signal to the sector that it is valued and appreciated.

- Enhanced sector communication and collaboration: Representatives wanted better communication infrastructure and collaboration opportunities within the sector, particularly for individual workers. They felt this would enable efficient responses to the challenges of a future pandemic. To be effective in an emergency response, they wanted collaboration to foster strategic thinking rather than focusing on competition within or between different parts of the cultural sector.

- More flexible financial support mechanisms: In the event of a future pandemic, financial support should be flexible and recognise the complexities of the cultural sector, particularly the different ways that individuals (such as sole traders and freelancers) and cultural organisations access and receive financial support. They believed that this would ensure that financial support is practical, accessible and meets the needs of the sector’s workforce and business models.

Annex

Roundtable structure

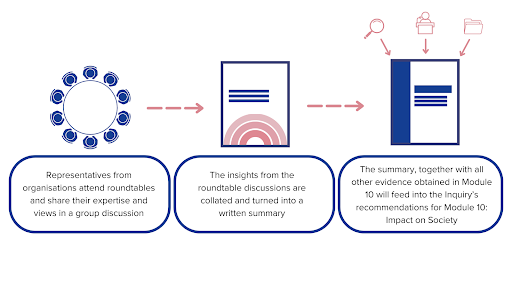

In May 2025, the UK Covid Inquiry held a roundtable to discuss the impact of the pandemic on organisations and individuals working in the cultural sector. This roundtable included one breakout group discussion.

This roundtable is one of a series being carried out for Module 10 of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry, which is investigating the impact of the pandemic on the UK population. The module also aims to identify areas where societal strengths, resilience, and or innovation reduced any adverse impact of the pandemic. The roundtable was facilitated by Ipsos UK and held online.

A diverse range of organisations were invited to the roundtable; the list of attendees includes only those who attended the discussion on the day. Attendees at the breakout group discussion were representatives for:

- Arts Council England

- Arts Council Northern Ireland

- Creative Scotland

- Broadcasting, Entertainment, Communications and Theatre Union (Bectu)

- Equity

- Esmée Fairbairn Foundation

- Musicians’ Union

- Music Venue Trust

- Paul Hamlyn Foundation

Glossary of terms

| مدت | تعریف |

|---|---|

| Screen sector | The screen sector encompasses the film, television, animation, video games, and visual effects (VFX) industries, including content development and production to distribution, exhibition, and skills/education. It covers audio-visual content intended for platforms like cinemas, broadcast television, and streaming services. |

| واحد تاجر | A legal business structure in the UK where the individual owns and runs the business, and there is no legal distinction between the owner and the business itself. |

| Freelancer | A person who works for themselves on a self-employed basis, selling their services to different clients rather than being employed by one company. |

| Individual practitioner | A creative or cultural professional, such as an artist, writer, performer, or curator, who works independently or on a freelance basis to deliver creative projects, provide expertise, or develop their artistic practice. |

| Grassroots venues | A small, independent performance venue that serves as a primary platform for emerging artists and new music. |

Figure 1. How each roundtable feeds into M10