ਕਾਰਜਕਾਰੀ ਸੰਖੇਪ ਵਿਚ

This report does not represent the views of the Inquiry. The information reflects a summary of the experiences that were shared with us by attendees at our Roundtables in 2025. The range of experiences shared with us has helped us to develop themes that we explore below. You can find a list of the organisations who attended the roundtable in the annex of this report.

In February 2025 the UK Covid-19 Inquiry brought together representatives of organisations from the UK’s largest religions for a roundtable discussion to explore the impact of the pandemic and government restrictions on faith communities.

Representatives described how restrictions on religious gatherings and practices caused a profound sense of distress and loss among faith communities. They also reflected on the positive role of faith during the pandemic for people’s spiritual and emotional wellbeing, sharing how their religious communities supported one another providing practical and emotional support to more vulnerable members of their communities.

Faith communities found innovative ways to observe rituals and connect with others in their community, including online services, outdoor gatherings, and providing pastoral care remotely. This was seen as having a positive impact on wellbeing amongst those in faith communities.

However, in some cases, important religious practices could not be moved online. This was the case for Orthodox Jewish communities, where online gatherings were not permitted for certain religious activities. Similarly, in some Christian denominations the Eucharist or Holy Communion cannot be achieved in line with their beliefs online, and baptisms can only be conducted in person.

Representatives from the Muslim Council of Britain and Hindu Council UK thought that the pandemic impacted some religious communities more than others. The representative from the Hindu Council UK highlighted the poorer Covid-19 health outcomes seen among Black and Asian groups and the increase in health-related anxiety in their communities as a result. The representative for the Jewish Leadership Council described a rise in antisemitism due to the pandemic and the damaging impact of a conspiracy theory that Covid-19 was a Jewish disease.

Representatives described how pandemic restrictions and guidance significantly disrupted religious communities. They felt that the rapid changes meant religious leaders had to engage with civil servants to ensure government guidance was appropriate and sufficiently tailored for religious communities and their practices.

Representatives also described how religious leaders had to interpret guidance and communicate it to their communities, becoming trusted sources of information about pandemic restrictions. They often did this alongside providing pastoral care in very difficult circumstances. These roles for leaders were thought to be important, but they also described how the additional responsibilities and pressures led to emotional strain and burnout.

Representatives further spoke about how religious leaders felt they had to make the case that faith and religious practice should be seen as important given that it is core to many people of faith’s identity. Representatives were particularly frustrated and disheartened when religious spaces reopened for individual prayer at the same time as non-essential shops, and later when public worship was allowed alongside people being able to use swimming pools and visit pubs.

Some religious leaders found it difficult to build relationships with the government and this affected their ability to ensure the needs and experiences of faith communities were taken into account during the pandemic. In particular, representatives from the Muslim Council of Britain and the Hindu Council UK described having limited contact with the government and felt having a closer relationship would have been valuable in an emergency situation. Representatives agreed that the pandemic highlighted the need for better relationships between religious communities and government. They made suggestions for mitigating the impact of the pandemic on religious communities in future pandemics or emergencies.

ਮੁੱਖ ਵਿਸ਼ੇ

Impact on the role of faith

Representatives spoke about how the severe disruption to religious gatherings and practices during the pandemic brought a deep sense of distress and loss for people from faith communities. However, faith was described as a source of strength and meaning for many people, helping them to cope with the uncertainties and difficulties of the pandemic.

The representative for Churches Together in Britain and Ireland highlighted research conducted during the pandemic that found that 89% of church leaders in Scotland and Northern Ireland felt that faith helped people in their congregations to cope during the pandemic. Representatives also shared how the pandemic gave some people an opportunity to reconnect with their faith individually and with their community, and how this improved their sense of religious wellbeing.

| " | It was encouraging to see how much faith meant to people and to see people reconnecting with church during the pandemic.

- Churches Together in Britain and Ireland |

People of faith were also able to rely on others in their community for help, both practically and spiritually, even when faith was not able to be practised in the usual ways. Representatives shared how religious communities supported vulnerable people, ensuring those in need received help with essentials such as food parcels and medication, as well as emotional support via the phone to those isolated. The representative for Cytûn (Churches Together in Wales) described how the Inter-faith Council for Wales co-ordinated member faith communities in providing packs of toiletries to patients in hospital. This helped to maintain community and build resilience.

| " | The way people demonstrated their sense of godliness was their service to others.

- Muslim Council of Britain |

Representatives also described the vital role of local faith leaders in providing guidance to their communities and acting as a trusted source of information about key issues like government restrictions and vaccines. For instance, the representative for the Muslim Council of Britain described how misinformation spread among some religious communities about the Covid-19 vaccine, raising concerns about getting vaccinated, such as that vaccines were not halal. Some Christian communities were concerned that the Covid vaccine was ultimately derived from aborted fetuses which had been used in the past to create cell lines for scientific research. Representatives shared how religious leaders provided information to their communities in relation to these concerns about the vaccine to encourage uptake.

Pandemic challenges for faith communities

Representatives repeatedly emphasised the centrality of personal faith, religious practice and religious community for many people. Representatives felt frustrated by what they described as a lack of understanding that religious practice is a core aspect of people of faith’s identity. They felt it was offensive that the reopening of faith spaces for private prayer was delayed until the same time as reopening non-essential retail in June 2020 in England, Wales and Scotland1. Religious spaces then opened for public worship and weddings at the same time as hairdressers, pubs and cinemas in July 20202. This contrasted with the approach taken in Northern Ireland, where places of worship reopened for private prayer on 19 May 2020, ahead of non-essential retail on 12 June 2020.

| " | For many people faith is essential. And it was being banded with non-essential things like swimming pools, it was offensive. It wasn’t intended but that is how it came across.

- Cytûn, Churches Together in Wales |

Representatives also highlighted the disproportionate impact the pandemic had on some faith communities. The representative for the Muslim Council of Britain described a more significant impact on the Muslim community due to existing inequalities, including high levels of deprivation, unemployment and social exclusion. They shared how this was exacerbated by Muslims experiencing a higher Covid-19 mortality rate during the pandemic than other religions. The representative for the Hindu Council UK also discussed the anxiety their community faced because of the poorer Covid-19 health outcomes experienced by Black and Asian communities.

| " | There was fear and anxiety amongst Hindu faith groups because of the morbidities in the community and the lack of information about Covid-19 guidance and vaccines.

- Hindu Council UK |

Some representatives described how members of their communities experienced racism and were targeted by conspiracy theorists during the pandemic. The representative for the Jewish Leadership Council shared that there was a negative impact on the wellbeing of the Jewish community caused by a conspiracy theory that Covid-19 was a Jewish disease, and that this led to an increase in antisemitism. The Muslim Council of Britain representative described how political criticism of the Muslim community (whose gatherings had been said to have spread Covid-19) resulted in negative comments within the press and wider public discourse, leading to a sense that their religion had been singled out.

Representatives shared that they were not able to fully understand the impact of the pandemic on religious communities as death certificates do not capture people’s religious identity. The representative for the Muslim Council of Britain described how challenging it was to not know the impact of Covid-19 deaths on their community specifically. They said having that transparency would in future help them to be able to provide the appropriate level of support.

Impact on religious gatherings

The pandemic brought significant limitations on the many religious practices that involve people gathering in person. Representatives shared how these religious practices initially stopped and then were modified throughout the pandemic.

Representatives described how the pandemic restrictions meant many people could not observe their faith in a way that was consistent with their beliefs and longstanding practices. The changes also increased social exclusion and loneliness in religious communities. For example, the representative for the Hindu Council UK shared how older members of their faith community felt uncomfortable to attend the Temple due to the fear of catching the virus when restrictions were lifted.

Some faith communities were able to adapt by transitioning to online gatherings. They were able to offer communal prayer, regular religious worship and opportunities for social connection among those who practised faith. Switching to online gatherings was also noted as beneficial in enabling those newly reconnecting with their faith during the pandemic to participate in religious activity, thereby broadening the reach of religious gatherings.

In some cases, religious practices could not be replicated online, meaning they could not take place. For example, in some Christian denominations the Eucharist or Holy Communion ceremonies cannot be carried out online in accordance with their beliefs, and other rituals like baptisms can only be conducted in person.

The representative for the Jewish Leadership Council shared that in more progressive Jewish communities, moving some rituals online was seen as a viable, short-term solution given the exceptional circumstances. However, for Orthodox Jews, online gatherings raised serious questions about doctrinal legitimacy, allowing only for individual prayers. In Sephardi Jewish communities, the senior Rabbi issued guidance permitting online prayer in the first period of the lockdown, but it could not take place thereafter. Use of technology is also not permitted on the Sabbath for Orthodox Jews so online gatherings were not appropriate in this context, limiting the access of religious gatherings for some Jewish communities. In turn, this had an impact on community connection and support.

| " | Online religious gatherings were an option but there were disagreements about it within different parts of the community.

- The Jewish Leadership Council |

Representatives shared that not being able to mourn in accordance with traditional religious practices was particularly difficult for faith communities.

Faith can play a central role in processing grief and finding comfort, including through gathering with others. For instance, in the Jewish community important aspects of the burial process such as the Kaddish3 were not able to take place due to limits on the number of people attending funerals and burials, while practical elements of the burial process could not take place due to fear of infection from the deceased. The Muslim Council of Britain representative spoke about how challenging it was during the pandemic to find enough space to bury members of Muslim faith communities, given the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on Muslim communities.

| " | I remember going to local Mosques and asking them to double and triple the burial lots they had. There was an immense impact. What made it more painful was that it wasn’t on anyone’s radar.

- Muslim Council of Britain |

Representatives across different religions felt that restrictions on funerals were one of the main impacts on their faith communities during the pandemic, affecting people’s wellbeing and ability to grieve in a way that reflected the traditions of their faith.

| " | The best parts of faith practice supporting people through bereavement were denied by Covid-19, which has left scars and has drained a lot of people’s emotional energy along the way.

- Churches Together Scotland |

The representative for Cytûn described being able to conduct a funeral for a dispersed family online, which they had never done before. This meant that all relatives were able to attend. While recognising the benefits that hybrid gatherings could bring to help people participate in funerals and services from a distance, faith leaders stressed that online gatherings often did not feel like an adequate substitute for in-person gatherings and religious services.

There were also concerns across faith communities about unequal access to information and communication technologies (sometimes referred to as the ‘digital divide’) during the pandemic. This meant some members of religious communities, including older people, those without digital skills, those living in rural areas and those without access to the internet/broadband experienced barriers to accessing online religious gatherings.

Representatives shared that for online tools to be used in religious communities, religious leaders also had to be able to use technology confidently or find help from others to do so. Representatives said that many leaders were able to do so, but the representative for the Hindu Council UK described how older priests struggled to use technology in comparison to younger members of the clergy who were more familiar with this approach. Providing the digital infrastructure for online religious gatherings also came at a cost. The representative for the Church of Scotland described the substantial financial impact of introducing technology, alongside the broader financial impact of the pandemic on income, rents and loss of investment among some churches or denominations.

Representatives described other innovative ways in which different faiths observed rituals during the lockdown restrictions, such as drive-in church services, collective prayers in streets, online coffee faith gatherings, ‘live’ social media gatherings and the Ramadan at Home campaign (which involved virtual meals and live stream readings of the Quran and outdoor services in April and May 2020). They said these examples highlighted their communities’ strong desire to maintain connection with one another and to practise their faith. Representatives shared that these examples had a positive impact on their communities spiritual and emotional wellbeing and reminded them of the importance of faith in society.

| " | We rekindled the meanings of faith. I remember seeing a photo of terraced houses, everyone was in their own bubble but there was someone collectively leading prayer.

- Muslim Council of Britain |

Impact on pastoral care

Representatives described how in-person pastoral care is a core part of religious life for many faith communities. This includes faith leaders and other members of faith communities visiting people in their homes and hospitals when they are ill or need help. During the pandemic this was restricted, leaving people without the support they would usually have had.

Representatives spoke of new ways of delivering pastoral care, such as making phone calls to isolated and ill people, and how this provided some limited support to people in need. However, this was not felt to be an adequate replacement for in-person pastoral care as it could not offer the same level of emotional and spiritual support.

| " | The adaptations to pastoral care were not a complete replacement of personal, in the home, in the hospital type of care.

- The Church of Scotland |

As pandemic restrictions eased and in-person pastoral care could happen more, this was also seen as an effective way of providing Covid-19 related information and guidance to those who were digitally excluded and not engaged with government messaging.

For religious leaders and others in religious communities, providing pastoral care came with risks to their personal safety. Representatives described the difficulty of balancing the offer of care against the risks of transmission, and the need to follow restrictions that were not always clear. For example, the representative for Churches Together in Britain and Ireland described how those in ministry abide by the rule “to do no harm”, but adhering to this proved impossible during the pandemic. Providing individuals with pastoral support during the grieving process posed a public health risk due to potential virus transmission. However, not giving support also risked causing harm to those in need of spiritual and emotional care and this was difficult and uncomfortable for religious leaders who wanted to provide support.

| " | There was harm in every choice. If you were not there for people when their loved ones were dying, you knew that absence was going to cause harm and take elements out of that grieving process.

- Churches Together in Britain and Ireland |

The representative for Cytûn also described that even when the restrictions allowed in-person pastoral visits to continue, some members of the clergy (particularly those who were more risk averse) wanted more guidance on how to protect themselves and others from the virus, with greater clarity about whether they should conduct in-person pastoral visits or not.

Despite the challenges, pastoral care was seen as a vital source of emotional and spiritual support, with providers making concerted efforts to deliver it as effectively as possible.

| " | The benefit for our community, listening to sermons, being involved in prayer, giving that sense of meaning, it gave people the ability to move on. Given all the death and the disproportionality they suffered, it made sense of the why.

- Muslim Council of Britain |

Impact of government guidance

Representatives discussed how local religious leaders were at the forefront of interpreting and communicating government guidance on religious practice within their communities. They shared how they had to do this during the early stages of the pandemic, at a time when they felt they had limited engagement or guidance from the government. This was described as an additional task alongside their day-to-day roles, which put more strain on religious leaders.

Representatives also described religious leaders feeling apprehensive about sharing guidance due to concerns that their interpretation did not abide by government rules and could put people at risk. The representative for Faith Action described wanting clearer guidance from the government on what faith communities could and could not do, so that religious leaders did not have to interpret it themselves. They described their organisation’s role in communicating guidance to faith leaders, clarifying what was allowed and what was not. They also highlighted the challenges they encountered in this process, particularly the difficulty in accessing the most up-to-date information on government websites.

| " | An opportunity was lost to engage further with communities to ask how we can adapt guidance to suit your communities. What does it mean for you? If this was done earlier, the guidance would’ve been taken more seriously than it was.

- The Hindu Council UK |

Representatives for the Muslim Council of Britain and the Hindu Council UK felt that they had limited access to the government during the pandemic. The representative for the Muslim of Council of Britain felt that having limited engagement with the government meant that they had to do their own tailoring of guidance, leading to concerns early on in the pandemic about communicating the wrong message without government reassurance.

However, other Christian representatives such as Cytûn shared examples of good engagement with government. They pointed to the Faith Communities Forum with the Welsh Government, which they said was used more in the pandemic. This relationship with the government made their community feel more supported and understood by the Welsh government.

Representatives described growing frustration with the guidance developed by the government that prevented them from practising faith in safer and alternative ways, to better balance the health risks and the spiritual needs of their communities, particularly as the pandemic went on. For instance, the representative for Faith Action felt that there should have been more encouragement for faith communities to gather outside given the positive impact this had on wellbeing and the reduced risks of spreading Covid-19.

Implementing government guidance at pace was felt to be difficult as it did not give religious leaders enough time to adapt and communicate with their communities. At times, changes to guidance and restrictions were made the evening before a planned service or event. The impact of this was that it became challenging for religious leaders, volunteers, and those attending to comply.

Representatives noted that on some occasions in each nation, when guidance was issued on a Friday, it was then not intended to come into effect and be followed by religious leaders until the following Monday. The representative from Churches Together in Britain and Ireland told us about how this would leave church leaders, with services to run on the Sunday, feeling as though they were adhering to rules that were about to change. This caused frustration and insecurity about whether religious gatherings were following the latest rules and keeping people of faith as safe as possible. The representative for Cytûn noted that there were logistical benefits to delayed implementation of new guidance. They described how in Wales new guidance announced on Friday usually came into force on Monday, which church leaders found advantageous as they had a full week to prepare, and could announce the changes on the first Sunday for implementation by the second.

Representatives discussed the impact of lockdowns being introduced close to religious celebrations. A local lockdown was announced a day before the start of Eid al-Adha on 31 July 2020, affecting communal prayers, eating together and other gatherings. In Wales, a national lockdown was announced on 23 December 2020, two days before Christmas. Although places of worship were not required by law to close during this lockdown, they were strongly encouraged to do so, and additional legal restrictions on gatherings were put in place. This affected carol services, midnight masses and Christmas Day services. Communicating the lockdown on 23 December 2020 to churches was felt to be difficult as those who had previously worked with local religious leaders to interpret guidance were already on holiday. Representatives explained that the timing of these lockdowns was difficult and disappointing for those preparing to observe these important festivals and for religious leaders who had to change plans quickly.

There were also differences in the restrictions and guidance in different UK nations, which representatives felt created a lack of clarity for faith leaders when trying to understand how to communicate the guidance to their religious communities and to ensure they were abiding by the appropriate rules. The representative for Cytûn described the difficulty for faith communities close to the English border, especially if guidance did not specify whether it was referring to England or the UK. This made it challenging for religious leaders to interpret and share guidance.

Representatives felt that the pandemic guidance was not always reflective of the nuances of faith communities and places of worship. The representative for Churches Together in Britain and Ireland felt that guidance produced for Christians was largely shaped by the needs of liturgically-ordered churches4. They thought that the impact of this was that guidance was not tailored for different religions and denominations, which in turn led to difficulties for religious leaders in understanding and applying government guidance in a way that was relevant for their religious community.

Representatives also discussed the impact of other pandemic measures like recording attendance and collecting contact details for the purpose of contact tracing. For some communities collecting this information was not seen as an issue. The representative for the Jewish Leadership Council said providing personal details when attending a synagogue was not out of the ordinary prior to the pandemic for safety reasons. However, the representative for the Muslim Council of Britain spoke about how providing details for contact tracing was a barrier to practising faith for some of those in their communities because of concerns about the Prevent duty or immigration enforcement5.

Longer term impact on religious communities

Representatives described how for some people, the pandemic reignited the importance of faith. The representative for Faith Action described increasing numbers of church leaders focusing more on community work that they had not been able to prioritise before the pandemic. However, they also noted that the renewed sense of community activity and support during the pandemic has not always been sustained after the pandemic.

| " | I found increasing numbers of church leaders talking to me about the realisation of the importance of community. Even reflecting on their pre Covid experiences and neglecting community work, that was something missing.

- Faith Action |

Representatives also shared how the pandemic changed the way faith is practised. For example, the representative for the Jewish Leadership Council shared that one synagogue’s weekday morning service used to have worshippers who would attend the service during their journey to work, but because people are working from home more the service no longer runs. However, new services have been introduced at other times, and Saturday morning services have been shortened to engage more people. Representatives also shared how the use of online platforms for religious services have continued.

The representative for the Church of Scotland shared that not all previous attendees have returned to their churches. The pandemic was also described as having accelerated retirement among clergy who had health issues or who no longer felt comfortable in groups of people. The representative for Cytûn described how there has been an acceleration in church closures in Wales partly because there were previously more church buildings than could be maintained, but also because of the pandemic leading to clergy retiring early and a decline in worshippers attending churches.

There was also discussion about the longer-term impacts on volunteers. The representative for the Church of Scotland shared that church volunteers were now less willing to take on roles and responsibilities, linking this to the pressures of the pandemic. For example, reopening churches created additional burdens on volunteers because they had to make spaces safe, such as by maintaining social distancing and carrying out more thorough cleaning. Representatives described how the pressures of the pandemic and the additional tasks caused burnout amongst volunteers.

Lessons for future pandemics

In reflecting on the pandemic, representatives highlighted the valuable role that religion plays in UK society. Representatives suggested key lessons that can be learned from the experience of faith communities to better prepare for and respond to future pandemics and reduce impact on faith communities.

- Recognise the importance of faith: Representatives felt that the importance of faith to many individuals should be recognised in pandemic decision making, including recognising that religious spaces are distinct from non-essential retail and leisure. Enhancing government literacy about religious history and practices was felt to be crucial, to improve the relevance and effectiveness of guidance during emergencies. To maintain effectiveness, representatives felt that government guidance should avoid blanket approaches and instead provide nuanced directions respecting individual religious contexts. If government guidance was clear, relevant, and specific to religious communities, representatives thought it would support religious communities to implement practices confidently and accurately.

- Strengthen communication between government and all faith communities. Representatives said that they would like to build and maintain strong relationships between government and faith communities to have the communication structures in place in the event of a future pandemic or civil emergency. Representatives felt that strengthened communication would help build trust and ensure that future guidance better reflects religious practice. This would give religious leaders confidence that they are sharing the appropriate guidance with their communities.

- Consider how communication can be supported through a formal network of different faith communities. Representatives discussed the need to form networks that would enable them to work together and mobilise in the event of a national emergency. There were examples of pre-existing networks such as the faith task force and the faith forum, however, these typically were activated in an emergency and are no longer used as frequently. Representatives shared that the pandemic showed that different faith communities can work well together, particularly when they have a common cause and that these forums could be active consistently. If these networks were in place, representatives thought that it would enable the rapid mobilisation of faith communities to support one another and share examples of best practice in how to support religious communities.

- Collect consistent faith data. Representatives reflected that data about faith is often not collected. For example, death certificates do not record faith. This meant it was not possible to understand the impact of Covid-19 deaths on people from different faith communities during the pandemic. Representatives felt that better faith data would enable better evidence, for example about faith groups having higher morbidity or lower vaccination rates and that there could then be further outreach to those communities to help them to access support and available vaccines.

- Trust religious leaders to share information. Religious leaders considered themselves vital in contextualising and communicating guidance to their communities. Representatives felt that there is a need to build on the trust that faith communities have in their leaders to communicate more effectively, including using faith networks to access harder to reach and more isolated people. In doing so, religious leaders could help address the spread of misinformation and build better relationships with their communities.

Annex

Roundtable structure

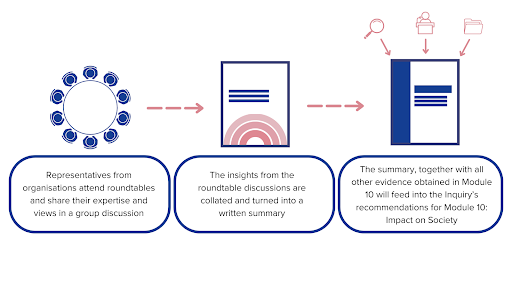

In February 2025, the UK Covid-19 Inquiry brought together seven representatives of organisations from the UK’s largest religions for a roundtable discussion about the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and government restrictions on faith groups and places of worship.

This roundtable is one of a series being carried out for Module 10 of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry, which is investigating the impact of the pandemic on the UK population. The module also aims to identify areas where societal strengths, resilience, and or innovation reduced any adverse impact of the pandemic.

The half-day roundtable with religious leaders was facilitated by Ipsos UK and held at the UK Covid-19 Inquiry Hearing Centre.

A diverse range of organisations were invited to the roundtable, the list of attendees includes only those who attended the discussion on the day. Attendees at the roundtable were representatives for:

- Churches Together in Britain and Ireland (CTBI)

- The Church of Scotland*

- Cytûn, Churches Together in Wales*

- Muslim Council of Britain

- Jewish Leadership Council

- Hindu Council UK

- Faith Action

*The Church of Scotland and Cytûn attended as part of the CTBI delegation

Module 10 roundtables

In addition to the roundtable on faith groups and places of worship, the UK Covid-19 Inquiry has held roundtable discussions on the following topics:

- The Key workers roundtable heard from organisations representing key workers across a wide range of sectors about the unique pressures and risks they faced during the pandemic.

- The Domestic abuse support and safeguarding roundtable engaged with organisations that support victims and survivors of domestic abuse to understand how lockdown measures and restrictions impacted access to support services and their ability to provide assistance to those that needed it the most.

- The Funerals, burials, and bereavement support roundtable explored the effects of restrictions on funerals and how bereaved families navigated their grief during the pandemic.

- The Justice system roundtable addressed the impact on those in prisons and detention centres, and those affected by court closures and delays.

- The Hospitality, retail, travel, and tourism industries roundtable engaged with business leaders to examine how closures, restrictions and reopening measures impacted these critical sectors.

- The Community-level sport and leisure roundtable investigated the impact of restrictions on community level sports, fitness and recreational activities.

- The Cultural institutions roundtable considered the effects of closures and restrictions on museums, theatres and other cultural institutions.

- The Housing and homelessness roundtable explored how the pandemic affected housing insecurity, eviction protections and homelessness support services.

Figure 1. How each roundtable feeds into Module 10

- This date differed by nation in the UK: 19 May 2020 in Northern Ireland; 15 June 2020 in England; 19 June 2020 in Scotland; 22 June 2020 in Wales

- The date of reopening for public worship varied by UK nation: 29 June 2020 in Northern Ireland; 4 July 2020 in England; 13 July 2020 in Wales (although weddings had been permitted in Wales from 1 June 2020); 15 July 2020 in Scotland.

- Kaddish Yatom (Mourner’s Kaddish) – said by mourners at specified points of the prayer service. The purpose is to praise God as a source of merit for the deceased.

- Liturgically-ordered churches are those that follow a prescribed order of worship, often with a fixed structure and set prayers, as opposed to non-liturgical churches which may be more spontaneous and less formal.

- The Prevent duty was established by the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 and places a duty on specified authorities such as education, health, local authorities, police and criminal justice agencies (prisons and probation) to have ‘due regard to the need to prevent people from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism.