Soo koobida fulinta

This report does not represent the views of the Inquiry. The information reflects a summary of the experiences that were shared with us by attendees at our Roundtables in 2025. The range of experiences shared with us has helped us to develop themes that we explore below. You can find a list of the organisations who attended the roundtable in the annex of this report.

This report contains descriptions of domestic abuse and mental health impacts. These may be distressing to some. Readers are encouraged to seek support if necessary. A list of supportive services is provided on the UK Covid-19 Inquiry website.

In April 2025 the UK Covid-19 Inquiry held a roundtable to discuss the impact of the pandemic and the measures put in place on both adult victims and survivors of domestic abuse and domestic abuse support services. To note, the impact of domestic abuse on children and young people is being examined separately as part of the Inquiry’s Module 8 investigation. The three breakout group discussions included third sector and grassroots and specialist domestic abuse and safeguarding organisations, as well as government, legal and justice organisations and services. This report summarises key themes arising from all three discussions.

Representatives described the profound impact of pandemic restrictions on victims and survivors of domestic abuse, greatly exacerbating the risks they faced and the harms they experienced, as well as making it more difficult for them to seek help. Domestic abuse and rape cases became more frequent and severe during the pandemic, with changes in the patterns of domestic abuse-related deaths. While deaths due to abusive relationships decreased during this period, there was a small increase in other types of family homicides, often linked to mental health pressures. Representatives thought that victims and survivors were put at greater risk because the messaging on the requirement to stay at home did not make clear that victims and survivors of domestic abuse were considered ‘at risk’ and could legally ‘break’ the restrictions and leave home for safety reasons and to access support.

Representatives were particularly concerned that the requirement to stay at home was exploited. They described how perpetrators used the greater proximity and time spent together to increase the frequency and intensity of abuse they carried out. Victims and survivors also did not have the usual support from community networks and had limited opportunities to access formal support services.

Reports of domestic violence to the police were low at the start of the pandemic given victims and survivors were either unable to report as they were trapped with their perpetrator, or because they were not sure if it was possible to report to police during a public emergency. However, reporting figures increased as lockdown restrictions began to ease. Representatives felt that the level of reporting did not reflect the actual number of domestic abuse incidents during that early pandemic period. Although domestic abuse often goes unreported, they thought even fewer people were reporting offences during the first lockdown as emergency services were overwhelmed or support was not available.

Similarly, the demand for domestic abuse and safeguarding support services was also said to be low at the start of the pandemic, but increased as victims and survivors were able to have more time outside the home or away from the perpetrators of their abuse.

Representatives described the huge efforts made by specialist and third sector organisations to adapt quickly and step up to the increased demand for support, despite often initially lacking the resources to do so. The demands put workers at risk of burnout and negatively impacted their mental health. Representatives also discussed how the closure of local authority service providers placed greater strain on third sector, grassroots and specialist domestic abuse charities. These organisations described being beyond their capacity during the pandemic, often unable to take referrals.

Representatives from grassroots and specialist organisations commented that there was a lack of additional funding during the pandemic and that the processes for applying for funding were challenging. However, representatives from third sector charities shared some examples of how reduced red tape enabled greater access to funding. This funding supported these organisations to provide services during the pandemic.

The pandemic restrictions meant that many services had to shift online. Representatives from government, legal and justice organisations said that prior to the pandemic they had the digital infrastructure already in place, including laptops and digital meeting technology, which allowed them to adapt to the pandemic. The transition to online services was more challenging for smaller, community-based domestic abuse and safeguarding charities that had been largely offering face-to-face services before the pandemic and did not already have the appropriate technology.

Representatives spoke of the challenges faced by victims and survivors in accessing digital services, particularly for those:

- living in rural areas,

- lacking reliable internet access,

- without digital skills,

- unable to afford digital equipment, and

- that faced language or accessibility barriers.

Perpetrators during the pandemic would sometimes control access to technology, which made it harder, or impossible, for some victims and survivors to access support from friends, family, or formal support services.

The pandemic had specific impacts on some groups of victims and survivors. For example, victims and survivors with no recourse to public funds and migrant women faced difficulties accessing the online or telephone support available during the pandemic. This was because they lacked the means to purchase telephones or data, access WiFi or other technological equipment. They also faced language barriers and were fearful that information shared online could be sent to the authorities and affect their immigration status. Without British Sign Language interpreters for government messaging, d/Deaf victims and survivors did not receive basic information about the rules and restrictions, which representatives said perpetrators took advantage of to control victims. Domestic abuse and safeguarding workers, as well as interpreters, were also not considered ‘key workers’ and therefore unable to provide support in person to victims and survivors.

It was harder to provide access to safe accommodation during the pandemic. Providers faced challenges of capacity due to extra demand for safe accommodation, a reduction in available spaces to comply with social distancing guidelines, and victims and survivors often having nowhere to move during the pandemic. Access to safe accommodation was a ‘postcode lottery’ according to representatives, with varying availability across the UK and across different demographic groups. This meant victims and survivors in areas where there was no capacity, or with certain protected characteristics, could not access safe accommodation. Representatives also described confusion about what the lockdown and social distancing guidelines meant for refuges where individuals share communal spaces.

To reduce the impact of a pandemic on victims and survivors of domestic abuse, representatives felt that guidance and decisions need to consider the circumstances and experiences of victims and survivors. They suggested greater government collaboration with service providers about the support needed for victims and survivors of domestic abuse could prevent some of the problems with access to services during the pandemic. Representatives emphasised the importance of recognising domestic abuse and safeguarding workers, as well as additional support providers like British Sign Language interpreters, as ‘key workers’ in a future pandemic. This would help ensure they are given appropriate resources and support to allow them to continue their work, and avoid the difficulties d/Deaf victims and survivors faced in accessing support and information.

Mawduucyada muhiimka ah

Impact on the nature and frequency of domestic abuse

The requirement to stay at home during the pandemic made victims and survivors less safe as they often found themselves trapped at home with their abusers. Being at home with perpetrators during lockdowns increased stress, anxiety, and depression for victims and survivors.

Representatives described escalations in the frequency and severity of abuse during the pandemic for victims and survivors, who did not have the usual reprieve of being outside of the home or away from perpetrators some of the time. According to the representative for Women’s Aid England, at one point, their live chat service became overwhelmed with 21,000 people on the waiting list, causing the system to crash completely. The representative for Hourglass, an older people’s domestic abuse charity, shared that their services experienced a huge rise in calls and emails seeking support.

| " | Before Covid, we were dealing with 4,000 cases [of abuse] a year. Since then, because of the explosion in casework, now we’re dealing with 75,000 a year across all of the UK”– Hourglass |

Most representatives suggested that generally the pandemic did not directly lead to people becoming perpetrators of domestic abuse for the first time. Rather, the greater access to their victims, allowed existing perpetrators to carry out abuse more intensely and in different ways. However, there were some instances of perpetrators committing abuse for the first time. The representative for the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities noted that the financial and economic strain of the pandemic put additional pressure on households. They described how it had been reported by frontline services that there were people who had never experienced domestic abuse seeking support because their family’s financial situation had led to abusive behaviour beginning.

The nature of sexual assault in particular also changed during the pandemic. Rape Crisis England and Wales saw a rise in complex sexual abuse cases during the pandemic. For example, those co-habiting with their perpetrator during the pandemic often experienced a higher frequency and sometimes severity of rape and sexual assault given the increased opportunities the perpetrator had to abuse. As lockdown restrictions were eased and women were able to access services, Women’s Aid England saw there had been an increase in the frequency and extremity of what victims and survivors had suffered or were suffering, given they were trapped in homes with perpetrators for a longer period of time without a clear escape route.

| " | The weaponisation of every facet of the restrictions was used as an instrument of pain and suffering by perpetrators.”

– Women’s Aid |

Representatives described other ways perpetrators used the pandemic to assert control over their victims. For example, according to the representative for Welsh Women’s Aid, some victims phoned their helpline seeking advice because their children were not returned on time by their perpetrator in line with agreed child arrangements. This was because the perpetrators claimed the children had contracted Covid-19 and were required to isolate at the perpetrators’ homes in line with the test, trace and isolate rules. This created distress for the victim and fear for the child’s safety. The representative for ManKind Initiative also gave examples of perpetrators withholding their children from ex-partners and explained how in response the government issued a statement to say that pre-pandemic child arrangements had to remain in place.

The representative for ManKind Initiative shared how perpetrators were able to broaden their tactics of abuse towards male victims, such as preventing access to children, intensifying economic pressures and forcing men to go into work, putting them at risk of catching Covid-19.

Hourglass, an organisation supporting older people experiencing abuse, described how sexual abuse cases reported to Hourglass towards older people doubled during the pandemic. They said the majority of their calls related to familial abuse, with calls relating to abuse perpetrated by neighbours also increasing significantly during this period, doubling from 3% to 6%. There was an influx of cases involving adult grandchildren committing abuse when staying with their grandparents or great-grandparents, because their parents worked in key worker settings and tried to limit their contact with their children to avoid exposure. Restrictions on leaving the house gave more of an opportunity for perpetrators within older people’s homes to commit psychological, sexual and physical abuse.

The National Police Chiefs’ Council saw a rise in family homicides during the lockdowns. They stated that this included parents being killed by adult children and an increase in younger children being killed by a parent. The representative for Southall Black Sisters described an increase in women being killed by their sons in 2020, which they linked to the lack of mental health support options available during the pandemic. Hourglass shared that nearly half of adult family homicide victims during the pandemic were over 65 years old.

By contrast, the National Police Chiefs’ Council representative discussed how homicides by intimate partners reduced slightly during lockdowns. Similarly, Southall Black Sisters described how the percentage of women killed as a result of men’s violence decreased during the pandemic. Both organisations suggested this was because perpetrators felt more in control of victims as they were less able to leave during the lockdown restrictions – Southall Black Sisters made clear that homicides by male partners are usually the result of separation.

Representatives spoke about the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on migrant victims and survivors, who had no recourse to public funds. These victims and survivors were more likely to be trapped by their perpetrators given they could not access any statutory emotional, health or financial support. The Latin American Women’s Rights Service, Solace Women’s Aid and Southall Black Sisters reported cases where victims and survivors had lost insecure, gig economy1 work at the beginning of the pandemic. They told us that perpetrators took advantage of victims’ inability to support themselves financially to exert greater control over them.

Impact on reporting domestic abuse to the police

The increase in intensity of abuse during the pandemic was not initially reflected in increased reporting to the police or an increased demand for domestic abuse support.

Representatives stressed that low levels of domestic abuse reporting to the police were not unusual before the pandemic. They said that many victims and survivors do not report domestic abuse or pursue cases and victims and survivors often do not report domestic abuse incidents immediately after they occurred. For these reasons there are significant gaps in knowledge relating to perpetration of abuse.

| " | A person experiences domestic abuse maybe 10 times before they will report it. It depends where someone is on their journey. You can go from someone who has lost their temper and there is one incident to someone who deliberately has a campaign of abuse”.

– Welsh Local Government Association |

However, as lockdown eased there was an increase in reporting of domestic abuse and referrals to support services. Representatives saw this as an indication that perpetrators had been exerting greater control during periods of lockdown restrictions. They also attributed this increase in reporting as restrictions eased to victims and survivors not knowing whether they were able to report domestic abuse during an emergency, or if the police would be able to do anything about their situation given the lockdown. This pattern of increased reporting continued, with the representative for Rape Crisis England and Wales noting that 2021-22 saw the highest annual figure of recorded rape offences in England and Wales to date.2

| " | Staff members said it got ‘eerie’ when lockdown came in because the services changed… as restrictions were lifted we saw an increase in people accessing us, people would say “I didn’t know I had any options I thought I would have to sit through this.” The messaging didn’t get through.”

– Solace Women’s Aid |

The pandemic restrictions led to challenges for the court system and this was said to have affected domestic abuse cases. Courts were shut down with limited emergency processes put in place. This created longer waiting times and unclear expectations on whether hearings would take place in-person or online and led to a reduced trust in the justice system. It caused some victims and survivors to question whether to continue with cases. The court delays also had a negative impact on the wellbeing and feelings of safety for victims and survivors. Representatives felt that these challenges highlighted the need for greater flexibility and innovation in the court system to better support victims and survivors of domestic abuse.

| " | We still have a backlog [of unresolved legal cases] in Northern Ireland blamed on Covid. There were no emergency processes put in place. There was difficulty and delays with getting orders extended when orders expired.”

– Women’s Aid Federation Northern Ireland |

Government agencies and legal and justice services reflected that one adaptation which proved effective during the pandemic was the transition to online court hearings for domestic abuse cases, particularly for non-molestation orders, as victims did not have to be in the room with their perpetrator. However, this was not sustained and most courts have since returned to in-person hearings.

Impact of government guidance and engagement

Representatives were concerned about the impact of government messaging early in the pandemic that people should “stay home, stay safe” to protect the NHS and save lives. They thought this did not acknowledge that some people did not feel safe at home and they thought this messaging discouraged people who were experiencing domestic abuse from seeking help for fear of breaking the restrictions.

| " | The communication around restrictions was so unclear that ‘stay safe at home,’ for a lot of women, they thought it was illegal for them to leave the house.”

– Scottish Women’s Aid |

The representative for ManKind Initiative felt that government communications and messaging were not inclusive of male victims and survivors. This led male victims and survivors to feel excluded from the narrative about domestic abuse and not supported.

Third sector domestic abuse and safeguarding organisations described how their engagement with the government enabled them to inform the government about the impact of their messaging and guidance on victims and survivors of domestic abuse. In particular, Women’s Aid England felt their regular meetings with the Home Office and other agencies helped government guidance and communications to better meet the needs of victims and survivors as the pandemic progressed.

On the other hand, representatives from grassroots and specialist organisations felt ignored by both national and local government as the pandemic progressed. They thought the impact of this was that the government restrictions and messaging did not reflect the needs of the victims and survivors they represented. For example, the representative for the Latin American Women’s Rights Service felt that restrictions did not consider pre-existing inequalities experienced by victims and survivors that were exacerbated during the pandemic. They said those in insecure, gig economy work (including many migrant women with whom the charity works) often did not have access to furlough, or for those with no recourse to public funds, any form of statutory financial or other forms of support, making them more dependent on perpetrators and less likely to receive or be aware of support. As a result, they felt that some of the most vulnerable victims and survivors were not protected.

More generally, representatives thought the guidance lacked clarity on how restrictions applied to domestic abuse services and to victims and survivors. Government restrictions did not apply to those at risk of ‘harm’, but Solace Women’s Aid felt that the definition of ‘harm’ was not made clear to support services or victims and survivors. Charities described how victims and survivors can often minimise their experiences of abuse, and the lack of clarity around ‘harm’ meant that people did not seek help for fear of repercussions from breaking the restrictions. They spoke of occasions when they would get clarity from the government on this, but then restrictions were changed and that clarity was lost.

| " | People need to be told very clearly what “harm” means so that they don’t minimise their experience. You need to be very clear on what kind of support is available out there.”

– Solace Women’s Aid |

Third sector domestic abuse organisations had to step in to communicate what ‘harm’ meant and provide clarity on whether people could leave their house or access support. The representative for SignHealth said that they had to fill in the gaps in government messaging by translating all government guidance, including that about people ‘at harm’, into British Sign Language so that d/Deaf victims and survivors could understand the situation and their rights.

The representative for the National Police Chiefs’ Council noted that the level of confusion surrounding the restrictions encouraged their organisation to share guidance through the media, local authorities and via the “Ask for ANI” scheme in pharmacies to support victims and survivors to know that they could seek support during the restrictions.3

| " | We experienced a lot of confusion about restrictions and what it meant. We did a lot of things with media at the time saying: ‘You can keep seeking help, you can leave your home if you’re living in fear. If you’re fleeing your perpetrator, you can leave’.”

– National Police Chiefs’ Council |

Impact on accessing support

Lockdown restrictions meant victims and survivors could not rely on their normal support networks. This made them feel alone, isolated and more fearful. The representative for the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities described how the restrictions limited access to extended family and to safe community spaces like libraries.

| " | What you saw and what we continue to see is not only did we put people in their own homes with a perpetrator, we took all the services from the whole system away.”

– Convention of Scottish Local Authorities |

The shift to online services excluded those without access to digital technology or reliable internet connection. This was particularly the case for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and rural communities. There were also concerns that those without digital skills or confidence were excluded, in particular older people experiencing abuse. For example, the representative for the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities reflected that they had been reaching more older women in person just as support was moving online, making it difficult for those women to access help during the pandemic.

| " | Digital exclusion isn’t just about having the tech, it’s having the tech and competence to use the tech. Wales is a bit rural, the hopeless fluctuating signal. There is false confidence that there is a digital solution, those people can’t use the digital solution.”

– Welsh Women’s Aid |

Similarly, the representative for Hourglass felt that isolation from family, community support, and digital services during the pandemic was particularly acute for older victims and survivors.

| " | Digital divide hits older people more than anyone else, the people they trust were not in the room anymore, abuse and coercive control was rife.”

– Hourglass |

The use of online services also added language barriers for many victims and survivors. Representatives described the problems with access for d/Deaf people who needed British Sign Language or a screen reader. Those who did not have English as their first language also faced barriers.

The representative for SignHealth shared the specific difficulties faced by d/Deaf people who no longer had access to face-to-face support. This meant that their organisation had to scale up their domestic abuse support service to offer it nationwide. However, there were challenges in finding interpreters, particularly for languages other than British Sign Language. Online translation and interpretation facilities took time to set up, meaning those who used British Sign Language were excluded while this happened. SignHealth said perpetrators took advantage of d/Deaf victims’ inability to access government Covid-19 press briefings containing information about rules and restrictions as they were not translated into British Sign Language. Perpetrators were able to intensify their abuse towards d/Deaf people as a result.

The shift towards online information and support allowed perpetrators to control victim access by limiting access to technology. In doing so perpetrators stopped victims from connecting with others, accessing support services and staying informed about pandemic restrictions. This could include preventing access to online support services or digital support networks such as WhatsApp groups, including with friends and family.

| " | One of the different ways through which perpetrators abused victims was data control – if you’re providing services only remotely, and you don’t have credit on your phone/no access to Wi-Fi, or your perpetrator turns this off, victims would be isolated and could not contact statutory services.”

– Latin American Women’s Rights Service |

The representative for the National Police Chiefs’ Council described how the move towards online working encouraged police forces to set up new ways for victims and survivors to access support. In Cheshire and Cumbria, police forces set up Facebook Groups for victims and survivors to access support on their phone without it being visible to perpetrators.

Some domestic abuse services shifted to offering outdoor services in addition to online support. The Rape Crisis England and Wales centres developed online services and provided alternative therapies such as Walk and Talk4 and virtual group work. However, these adapted services did not always meet the needs of survivors with disabilities, and therefore access to support became even more limited for certain groups.

Solace Women’s Aid highlighted that the lack of access to medical services and other services that victims and survivors might ordinarily use alone meant that the signs of domestic abuse were not picked up by safeguarding teams, which in turn prevented signposting to tailored support.

Third sector representatives spoke about how a reduced offering and outreach from statutory services meant that many victims and survivors had to advocate for themselves to access support and prove that they were eligible. This experience could make victims and survivors feel that their experience of abuse was not believed or worthy of support.

| " | We saw statutory services refusing to look into whether a woman was eligible for support or not…this was especially the case for those with no recourse to public funds.”

– Southall Black Sisters |

In addition, representatives said that the lack of access to mental health services also meant that many victims and survivors reached crisis point without adequate support. Women’s Aid England shared findings from a survey they conducted, published in a report called ‘Perfect Storm’. This found that ‘50% of survivors reported a significant deterioration in their mental health during the pandemic’ due to being trapped at home unable to access support, while experiencing worsening coercive control, emotional and physical violence.

| " | Because of the impact of the pandemic, women were coming to us because their mental health reached crisis point, exhibiting suicidal feelings, ideation. Very few people had access to mental health support.”

– Solace Women’s Aid |

Impact on support provision

Statutory services such as social services were often closed or offered more limited support for victims and survivors of domestic abuse during the pandemic. Specialist and grassroots services described that because of their closure, statutory services were often referring more, and increasingly complex, cases to community organisations, particularly as restrictions were lifted. The representative for Southall Black Sisters said this put a strain on their services at a time when they already had high demand. Their service saw a 138% increase in calls to their helplines between the end of April and June 2020. As restrictions began to ease, victims and survivors were able to access more support, with some of these calls being referrals from other professionals in the sector. ManKind Initiative equally attributed some of their increased demand to statutory services shutting down during the pandemic.

| " | We saw an increase in traffic for our website, and our phone lines. The statutory services agencies were shutting their doors thus impacting community-based services and ourselves.”

– ManKind Initiative |

The representative for the National Centre for Domestic Violence highlighted that they were increasingly signposting victims and survivors to larger organisations, as in some cases smaller grassroots organisations did not have the resources to manage the heightened demand. Consequently, larger third sector organisations like Women’s Aid also faced increased pressure.

The representative for Rape Crisis England and Wales described how mental health and other social services closing, or operating limited services, meant they were unable to refer victims and survivors for ongoing support. This meant that centres were holding increasingly complex cases without the level of holistic support from statutory agencies, increasing the risk of harm to survivors and the wellbeing of staff who themselves faced additional pressures during the pandemic.

| " | Lockdown made victims feel very alone, isolated and threatened.”

– Welsh Local Government Association |

Representatives felt that the pre-existing funding challenges and the lack of access to additional funding during the pandemic put domestic abuse and safeguarding charities under greater pressure. Representatives from the National Police Chiefs’ Council and the National Centre for Domestic Violence discussed how the application process for additional funding was particularly difficult for smaller charities who were not as connected to local government and less familiar with, or without the capacity to engage in, their application processes. As a result, they were often not able to access the additional funding available.

The representative for the Local Government Association also described how there was confusion around funding messaging and funds being allocated between government and local authorities in England. This meant that additional funding for the sector was not available until May 2020 despite it being promised earlier, making it difficult to ensure services could meet demand.

The Latin American Women’s Rights Service representative shared how grassroots and specialist services had to buy digital technology without additional funding and those working in support services had to work longer hours without additional pay. Rape Crisis England and Wales received additional funding for their centres during the pandemic, but this emergency funding was only temporary. This meant that they were unable to provide the longer term services that people who have experienced sexual abuse often require.

| " | Centres saw significant increases in funding through Covid but this wasn’t sustained. The sector doesn’t just need funding in response to a crisis but long-term sustainability to build resilience, respond to place-based needs and reduce the fragmentation of care pathways.”

– Rape Crisis England and Wales |

Representatives reflected on how provision of services changed as they moved online. This meant workers provided support remotely through online one-to-one and group therapy, as well as other approaches introduced or expanded during the pandemic such as Walk and Talk outside. According to the National Police Chiefs’ Council representative, statutory agencies already had the digital infrastructure in place prior to the pandemic (e.g. laptops and staff being able to work from home). They were therefore better equipped to adapt during the pandemic.

Some charity services that were focused on face-to-face support and drop-in services before the pandemic did not have the right technology in place to be able to immediately start working virtually. The representative for Latin American Women’s Rights Service explained that the sudden need to purchase laptops, equipment and set up online service delivery put a financial strain on their resources, resulting in some workers having to use their own devices to provide support. The shift to delivering online services during the pandemic also put a strain on specialist organisations like SignHealth who had to use their reserves to provide technological services like British Sign Language Health Access5. Although initially funded, the service had to be stopped during the pandemic as funding ran out and was not replaced.

| " | I would say the sector was left to fend for itself for a very long time. And that meant that while you were dealing with multiple emergencies, you had to put more resources into the operational side. What that meant for the frontline workers themselves was that they had to work longer hours, as well as use their own equipment. The whole sector was quite proud of what we achieved, but it was down to our decision to drive forward without the necessary support.”

– Latin American Women’s Rights Service |

Representatives from government, legal and justice organisations also discussed some positive impacts from the move to operating online during the pandemic. According to the representative for the Local Government Association, from June 2020 the shift online meant they were able to meet more regularly with the police, local authorities and other key partners which improved collaboration and the quality of public service response as a result. The representative for the Convention for Scottish Local Authorities described similar experiences, highlighting that Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference calls moved from monthly to weekly and bureaucratic barriers previously in place were broken down to share information more widely.

However, those representing local authorities spoke about how it became difficult during lockdowns to perform routine social worker welfare and safeguarding checks on the victims and survivors of known offenders. The representative for the Local Government Association said it was difficult for authorities to challenge refusal of entry if perpetrators claimed vulnerabilities around Covid-19 exposure for those that lived with them.

| " | It was more difficult with social workers to perform the checks you’d have wanted to go out and do without the lockdown. It provided a mechanism for those committing abuse to keep people and authorities at a distance that they couldn’t do previously. It challenged their ability to identify what was happening and to get the information from survivors about what was happening.”

– Local Government Association |

Representatives stated that not giving domestic abuse and safeguarding staff ‘key worker’ status limited the support they could access as a workforce. The representative for Women’s Aid Federation Northern Ireland described how their workforce was not able to access adequate Personal Protective Equipment and test kits for communal refuges, putting residents and workers in the refuge at risk of catching Covid-19. Representatives from third sector organisations described how domestic abuse professionals were expected to continue to deliver services without being considered key workers, causing significant concern about what was the right thing to do.

| " | When the government announced the initial lockdown, they did create a list of key workers. We tried to ensure that BSL interpreters were considered key workers, but they weren’t. This meant that d/Deaf victims really struggled to disclose.”

– SignHealth |

Representatives also highlighted the negative impact of the pandemic on the wellbeing of the domestic abuse and safeguarding workforce. Not being recognised as key workers made their work feel less valued. The representative for Welsh Women’s Aid said that being left out of the ‘clap for carers’ made staff feel excluded at a time when they were under strain and at risk of burnout. Representatives also shared that among their workforce were some people who had experienced abuse themselves. Similarly, some staff had mental health problems prior to the pandemic that were worsened due to the pressures of lockdown.

| " | The speed at which domestic abuse workers burnout and the need for support was great, especially as they were in this crisis environment where the narrative is that you cannot leave people behind.”

– Welsh Women’s Aid |

Impact on access to safe accommodation

Representatives had significant concerns about the impact of the pandemic on access to safe accommodation. The pandemic restrictions and social distancing measures resulted in reduced capacity at many refuges, making it difficult to accommodate those in urgent need. Furthermore, according to the representative for the Local Government Association, there was uncertainty in how refuges could operate while following restrictions, particularly around contact between people from different family units. Before the pandemic, Southall Black Sisters and Solace Women’s Aid operated an open-door policy, but they had to stop this during the pandemic. This prevented some victims and survivors from accessing safe accommodation.

The demand for safe accommodation during the pandemic was greater than the accommodation available. Solace Women’s Aid saw a doubling of referrals to refuges between early March and the end of April 2020, which was a challenge to accommodate. The representative for ManKind Initiative said that the increase in demand for safe accommodation could not be met because of a lack of availability, compounded by those already in safe accommodation having nowhere to move on to during the pandemic.

| " | It’s important to note that there are a patchwork of services across the country, they [domestic abuse services] are almost non-existent outside of urban, city areas.”

– Southall Black Sisters |

Problems with access to safe accommodation affected different types of people in specific ways and some groups more acutely. For instance, the representative for Hourglass said that many spaces that were normally used for older people were closed during the pandemic and that older victims and survivors could not always be moved to care homes due to the risk of Covid-19 transmission. They would end up staying in an abusive household even longer. The representative for Solace Women’s Aid also shared that for women over the age of 55, emergency accommodation is often preferred over a refuge as they can offer more independence and privacy, compared to shared living arrangements. However, emergency accommodation was said to be scarcely available during the pandemic.

| " | You might be surprised to learn that during the entire time of Covid-19 we [older people’s domestic abuse charity] only had three successful emergency [placements within] safe spaces.”

– Hourglass |

SignHealth’s representative explained how they had tried to refer d/Deaf victims to safe accommodation but many refuges could not make their service accessible to d/Deaf victims whilst abiding by restrictions and pandemic measures. For example, having to wear masks in a refuge made lip-reading impossible, which left d/Deaf people who often rely on lip-reading feeling isolated and frustrated. The representative for the Latin American Women’s Rights Service said that migrants and those without recourse to public funds also struggled to access refuges because they were afraid their data would be shared by those services, potentially affecting their immigration status.

-

-

-

-

-

- The gig-economy refers to a labour market where workers perform short-term tasks or ‘gigs’ through digital platforms, being paid per job completed rather than receiving a regular, permanent wage. Examples include ride-hailing drivers, food delivery couriers and cleaners.

- Office for National Statistics, Crime in England and Wales data year ending March 2022. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2022

- Ask for ANI is a codeword scheme that enables victims of domestic abuse to discreetly ask for immediate help in participating pharmacies and Jobcentres.

- Walk and Talk: Walk and talk therapy is a form of counselling where therapy sessions take place outdoors, typically while walking or sitting in nature. It aims to leverage the therapeutic benefits of the natural environment and physical activity to enhance the counseling experience.

- British Sign Language (BSL) Health Access was a free remote interpreting service, launched in 2020 by SignHealth in partnership with InterpreterNow, to enable d/Deaf people with on-demand access to medical services over the phone or via video calls.

-

-

-

-

Lessons for future pandemics

Representatives suggested key lessons that can be learned from the experience of the domestic abuse and safeguarding sector to better prepare for and respond to future pandemics.

- Proactive planning: Representatives felt that there should be planning and modelling for how the domestic abuse and safeguarding sector might be impacted by future pandemics. Representatives felt that this would help them to respond quickly to the needs of victims and survivors during a pandemic, such as providing temporary accommodation and providing tailored translation and communication tools. Representatives also felt that proactive planning would help provide the best possible tailored support for victims and survivors.

- Inclusion in planning: Representatives highlighted the importance of including those working in the sector in the planning and development of government policies and restrictions that take into account the potential impact on victims and survivors of domestic abuse. They thought it was essential that the voices of marginalised communities at particular risk of abuse (such as older people, d/Deaf and disabled people, those with no recourse to public funds and migrants) were included in policy planning to ensure their needs are not overlooked. Representatives also felt that the involvement of sector organisations, particularly grassroots and specialised organisations, was needed to ensure comprehensive and inclusive planning for a future pandemic.

- Recognition as key workers: Representatives thought that domestic abuse professionals and those ensuring services are accessible (e.g. interpreters) should be recognised as key workers in any future pandemic. This would help them to obtain priority access to Personal Protective Equipment and testing facilities and ensure sector workers felt valued, safe and able to deliver services appropriately. Representatives felt that identifying sector staff as key workers would also improve the wellbeing of staff working in domestic abuse and safeguarding services and support them to deliver high quality services.

- Digital and structural innovations: Representatives highlighted the need for investment and funding in digital infrastructure and tools to adapt quickly to emerging needs. They preferred a mixed support offer, including face to face services where possible, to better support those who are digitally excluded.

- Cross-sector collaboration: Representatives highlighted the need for cross-sector collaboration in responding to future pandemics between the third sector, government and private sector organisations. Representatives felt that fostering greater collaboration would enable services to share their skills and deliver domestic abuse initiatives together.

- Funding consistency: Representatives felt that to be prepared for a future pandemic they needed consistent and sufficient funding that did not require challenging and time-consuming application processes. They said this would support innovation and enable an effective response in a time of crisis and reduce the impact on victims and survivors.

- Online court hearings: Representatives felt there was a need for clearer guidance and flexibility on whether hearings take place online or in-person. They also felt that it can be more effective and efficient to have hearings take place online.

Annex

Roundtable structure

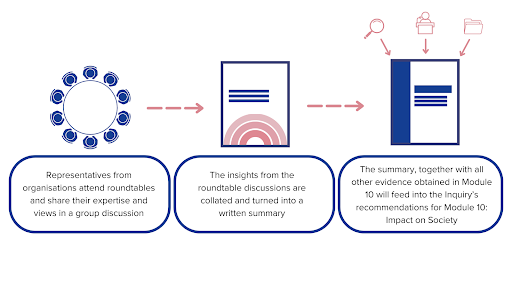

In April 2025, the UK Covid Inquiry held a roundtable to discuss the impact of the pandemic on victims and survivors of domestic abuse and the impact on domestic abuse and safeguarding support services. Three breakout groups discussions were held. One with third sector support networks, the second with grassroots and specialised services and the third with government, legal and justice organisations/services.

This roundtable is one of a series being carried out for Module 10 of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry, which is investigating the impact of the pandemic on the UK population. The module also aims to identify areas where societal strengths, resilience, and/or innovation reduced any adverse impact of the pandemic.

The roundtable was facilitated by Ipsos UK and held at the UK Covid-19 Inquiry Hearing Centre.

A diverse range of organisations were invited to the roundtable, the list of attendees includes only those who attended the discussion on the day. Attendees at the roundtable were representatives for:

Domestic abuse and safeguarding support services:

- Women’s Aid

- Welsh Women’s Aid

- Women’s Aid Federation Northern Ireland

- Scottish Women’s Aid

- Rape Crisis England and Wales

- Southall Black Sisters

- Latin American Women’s Right’s Service

- ManKind Initiative

- Hourglass

- SignHealth

- Solace Women’s Aid

Government, legal and justice organisations/services:

- National Centre for Domestic Violence

- Golaha Taliyayaasha Booliska Qaranka

- Local Government Association (LGA)

- Ururka Dawlada Hoose ee Welsh

- Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA)

Module 10 roundtables

In addition to the roundtable on domestic abuse support and safeguarding, the UK Covid-19 Inquiry has held roundtable discussions on the following topics:

- Miiska shaqaalaha muhiimka ah ayaa ka dhageystay ururada matalaya shaqaalaha muhiimka ah ee qaybaha kala duwan ee ku saabsan cadaadiska gaarka ah iyo khataraha ay la kulmeen intii lagu jiray masiibada.

- The faith groups and places of worship roundtable heard from faith leaders and organisations representing religious groups about the unique pressures and risks they faced during the pandemic.

- Miiska taageerada Aaska, aaska, iyo tacsida ayaa lagu falanqeeyay saameynta xayiraadaha aaska iyo sida qoysaska murugaysan ay u maareeyeen murugadooda intii lagu jiray cudurka faafa.

- The Justice system roundtable addressed the impact on those in prisons and detention centres, and those affected by court closures and delays.

- War-murtiyeedka warshadaha Martigelinta, tafaariiqda, safarka, iyo dalxiiska ayaa la kulmay hoggaamiyeyaasha ganacsiga si loo baaro sida xidhitaannada, xayiraadaha iyo tallaabooyinka dib u furista ay u saameeyeen qaybahan muhiimka ah.

- War-murtiyeedka ciyaaraha iyo madadaalada ee heer bulsho ayaa baaray saameynta xayiraadaha ay ku leeyihiin ciyaaraha heerka bulshada, jirdhiska iyo hawlaha madadaalada.

- The Cultural institutions roundtable considered the effects of closures and restrictions on museums, theatres and other cultural institutions.

- Shaxda guud ee Guryaha iyo hoy la'aanta ayaa lagu sahamiyay sida masiibada u saamaysay amni darrada guryaha, ilaalinta ka saarista guryaha iyo adeegyada taageerada hoy la'aanta.

Figure 1. How each roundtable feeds into M10